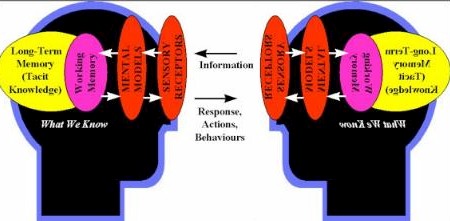

Three subjects combined into one post today. They’re connected, and you’ll see how as you read. (1) The Truth About Frames As I’ve mentioned before, I spent a good deal of time in 2003 doing debriefs with business colleagues after major presentations (my own and others’) to assess just how much knowledge was imparted, and how accurately: My conclusion was that almost no knowledge is transferred during business presentations, and not much during business meetings, either. That got me reading about frames, the mental mechanisms, lenses and filters through which we internalize what we see, hear and otherwise sense. George Lakoff has argued that different frames account for the inability of liberals and conservatives to communicate effectively with each other (or change each other’s minds), and that to bridge the gap you need to reframe an issue in a way that is understandable to your adversary, and which also allows them to see a different perspective ‘through new eyes’. He puts it this way: Frames trump facts. All of our concepts are organized into conceptual structures called “frames” (which may include images and metaphors) and all words are defined relative to those frames. Conventional frames are pretty much fixed in the neural structures of our brains. In order for a fact to be comprehended, it must fit the relevant frames. If the facts contradict the frames, the frames, being fixed in the brain, will be kept and the facts ignored.

So if we want to persuade people that a zeal for natural solutions and a reverence for nature is an essential part of the solution to the world’s problems, for example, we need to get people out of their anthropocentric (humans-as-separate) frames and create a new, credible ecocentric (humans-as-intrinsic-part-of-all-life) frames. Until we do so, we’ll be seen as romantics, hopeless idealists, neo-survivalists, even anti-humanists. And if liberals want to persuade conservatives of the value of universal health care and universal high-quality education, they shouldn’t be trying to appeal to conservatives’ sense of fairness and egalitarianism (these are liberal constructs) but rather to fundamental moral principles: “Working people shouldn’t be living in poverty” and “Everybody should have health care.” And rather that talking about the minutiae of Kerry’s programs in these areas, they should be hammering the Bush record using ‘grammar’ that conservatives relate to: “We’re weaker in education, and here’s why. We’re weaker in health care, and here’s why…” A similar approach is needed to bridge the gap between management frames and labour frames, between male frames and female frames, between theistic frames and agnostic frames. In fact, every individual has unique frames, that translate, ignore, or misconstrue the vast majority of what he or she hears from others. It’s amazing that such dysfunctional communication doesn’t cause more catastrophic consequences in business than it does, and it explains why repetition, to the point of being annoying, and many redundant conversations, are needed before important views, ideas and perceptions are imparted and understood. It also explains why so many couples keep arguing over the same things, again and again, without resolution. They might as well be speaking to each other in different languages. In many ways, they are. Reframing issues is a precarious and challenging process. It’s not a job for amateurs. But there is a simple and subversive way to reframe an issue: Tell a story. The story should have a moral, but it is not necessary (and it is sometimes unwise) to state the moral explicitly. The more I study and learn about stories and narratives, the more awesome and powerful I perceive them to be. My personal action plan to help prevent social, economic, political and ecological collapse of our planet by the end of this century currently includes these three things:

But I’ve become aware that making the transition to that better way to live is going to require billions of people to ‘buy in’ and be totally committed to a radically different philosophy, politics, economics, and social framework than the one we have been brought up to believe in. And I’m aware that some of the steps that may be needed to get there will be difficult and confront long-standing taboos — in fact I know I have lost some otherwise-sympathetic readers by merely mentioning the possibility of some of these steps, as a last resort. Clearly I need to reframe these arguments and possibilities in ways that are less controversial, confrontational, and off-putting to people. I’m beginning to believe that my novel is just the first of a whole series of stories I need to craft, if I have any hope of being credible and successful as anything more than an off-the-wall thinker who got a lot of other people thinking about the need for radical personal, social, political, technological, educational, and economic change, but couldn’t persuasively articulate how to get the job done. Progressives who care about the state of our world are going to have to become expert story-tellers, very quickly. I’m vowing to learn, and then to teach, that art, as a fourth major program to add to the three bulleted above. So look for a lot more about stories and narrative in the future in How to Save the World. Maybe we can learn together. (2) The Truth About Drug Costs In this week’s New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell smashes a lot of the prevailing wisdom about the skyrocketing cost of drugs. Here’s a synopsis, but please read the whole article if you have time, and if you haven’t subscribed to the New Yorker yet, this should convince you.

My only beef with the article is that Gladwell seems to be quick to blame patients for being all too willing to rush into their doctor’s office after they hear ads and ask if “X is right for them”. That’s asking a lot from patients who are dismally ignorant of medicine, prone to overdependence on their doctors, and gullible when they’re worried about the health of loved ones. (3) An Obscene Story Also in this week’s (Oct. 25th) New Yorker is writer Susan Sheehan’s heart-rending account of the life of Cassie Stromer, a 76-year-old widow living in Virginia who personifies perfectly America’s poor in this age of disappearing middle class. I can’t summarize this story, you need to read it in its entirety. And, alas, it’s not available online. It’s only 7 pages, so please seek it out in your store or library. This is a story everyone needs to hear. Her annual pension income is $9600, which puts her $300 over the poverty level and disqualifies her from full Medicaid benefits. Much of her income goes to pay for medical expenses, and the way she budgets her money so carefully and lives a meagre but dignified life is nothing short of heroic. So why is this story obscene? Here’s the last few sentences, which speak for themselves: This May, Cassie got some good news. Because of a formula involving her medical expenses, her rent was being reduced from $72 a month to $42. In September, however, she received a notice from the state telling her that her $58 Medicare premium would no longer be covered, meaning she would have to pay it herself. Earlier this month, Cassie’s lower denture broke again. “This time it’s shattered”, she says, “It’s harder to eat now. I can’t really chew anything.” She has to cut up her food into small pieces. She says there’s nothing she can do about it. “I don’t have any more money today than I did last February, and I won’t have any more tomorrow.”

Meanwhile, the f***ing politicians, bargaining in backrooms for favours for their corporate donors and friends while drinking expensive champagne and fifty-dollar entrees paid for by taxpayers, continue to spout the rhetoric that “most” Americans have good health care, and that it would be “too expensive” to provide universal health care to all, while insinuating that abuse of the system is widespread and that those that don’t have coverage are somehow responsible for their own misfortune. Cassie’s story belies these cynical and horrendous claims. And the fact that so many brave and proud Americans, tens of millions of undeserving poor with stories like Cassie’s, are mere pawns in this rich-man’s debate, is what’s obscene. |

It’s not so clear cut Dave – I’ve been on Nexium fr some time. I tried Prilosec because I really could not afford Nexium but it did not work anywhere near as well – and believe me I wanted it to.

Excellent point on frames. It explains a lot andrelates to the idea that it doesn’t matter howimportant your message is if you can only preachit to the choir. All sides tend to look for information that supports their existing beliefsand tend to discount the rest. Changing that dynamic is the key to breaking through. I’d liketo hear more on how.Some know this in the professional sense — don’tgive advice if they’re not paying for it (or at least asking for it). Otherwise, they’re just notlistening.Separately, the “buy in” on a new way of living requires “cash out” on the old which can be as daunting.

Doug: According to the article — Nexium is simply Prilosec with one of the two isomers removed, and its only verified effect is to raise the healing rate from 87% to 90% in one clinical trial of patients with ‘erosive esophogitis’. There was no medical reason to believe that removing one of the isomers would have any impact, it was just a crapshoot by AstraZeneca. Gladwell also says cimetidine (Tagamet) is just as effective for most patients and is much cheaper. Anyone else weigh in on this?

Dave’s blog post sketches an outline of the flawed structure of America’s health care system. And since America’s health care system is an expression of America’s culture and America’s values, those medical flaws express the fundamental flaws in our cultural system.The beginning of Peter Senge’s insightful book, _The Fifth Discipline_, describes how any person will make bad decisions when playing a role that rewards bad decisions. American health care rewards bad decisions. Thus *every role* in the American health care system leads to bad decisions. Patients, physicians, drug sellers, drug researchers, politicians….every participant reads from the only script our culture provides…the only story we know. Every participant is rewarded for playing a scripted role, and the flawed script yields flawed results.What Senge might describe as “stepping out of our flawed system” Lakoff might describe as “reframing”. Rather than searching for one role or one molecule to blame, let’s concentrate on reframing. We can transform health care–and our economy, our schools, our government–by reframing our culture to value people.

(see my blog on drug costs) the article didn’t mention the most obvious – value-based pricing. How do you think someone can charge a hospital $15,000 for one patient dose of Xigris (sepsis drug)? What would you pay to increase the likelihood by 30% that a loved-one would survive a massive infection and live for another year or two? $15,000 is what the market research shows. This is absurd.

I too read the New Yorker article, and it just killed me. And I really wished I could help this lady. I don’t have much extra money, but this lady has nothing. So I went on the internet and found her address. I’m sending photocopies of the article to friends with the address, and maybe we can make Cassie’s life a little easier. Since her full name and place of residence were given in the article, I hope this isn’t too intrusive. Anyway, her info (according to the Ultimate White Pages) is: Cassie Stromer, 8199 Tis Well Drive, Alexandria, VA 22306-3286. I am going to try to get at least $100 together from people at work, and maybe if enough people send money, Cassie can pay for the dental things she needs, and food and medicine as well. It sounds like even $10-20 makes a huge difference to her. Isn’t the internet marvelous???

Another example of this is how the debate on extending civil marriage rights to gays and lesbians is framed. One thing that liberals need to learn from neo-conservatives is how to better frame issues in terms favorable to the desired outcome. A good example is how anti-gay rights advocates have seized the movement for extending civil marriage rights as a way to bolster the religious political base and to oppose civil rights for gays and lesbians. They use message discipline along with discourse framing to get their message across – regardless of how their views are reported.