For the last few weeks I’ve been bouncing ideas on how to implement the principles in James Surowiecki’s book The Wisdom of Crowds off a variety of people in the public and private spheres. I think I’ve finally got a model that works. For those unfamiliar with the concept of the Wisdom of Crowds, here is just a bit of what I’ve written to get you up to speed:

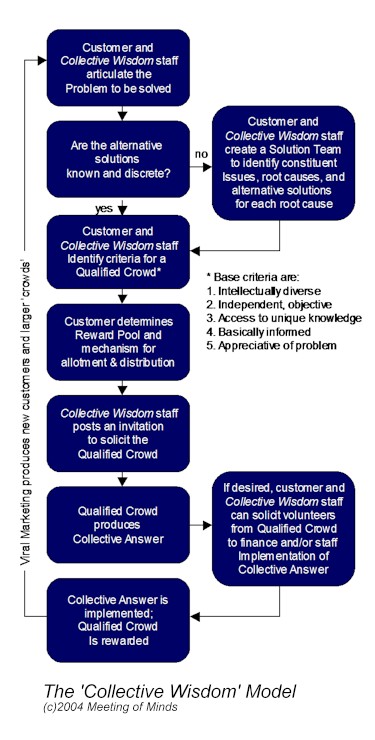

Tell me what you think of this approach, which is designed to integrate a lot of diverse applications: business, social, political, economic, artistic, scientific, or technological. You have a problem to solve or a decision to make, this model will help you do it better. Just to restate the basic principle: Many cognitive, coordination and cooperation problems are best solved by canvassing groups (the larger the better) of reasonably informed, unbiased, engaged people. The group’s answer is almost invariably much better than any individual expert’s answer, even better than the best answer of the experts in the group. The reason for this superiority is that each individual brings to the problem some valuable unique knowledge or perspective, and any errors in that knowledge or perspective are balanced off against those of others in the group, so the collective wisdom of the group is likely to be extremely accurate, reliable, knowledgeable, and predictive. If you’re skeptical, please read the book — Surowiecki presents dozens of examples to support this thesis. The average prediction of one such group, the Iowa Electronic Market, over the several months before the election, was that Bush would win by a comfortable 3% margin and that Republicans would make gains in both houses of Congress. They were exactly right. My ‘Collective Intelligence’ model realizes (a) that there are some things that crowds can’t do (they need to be given a problem with a discrete or quantifiable set of possible answers from which to choose), (b) that care must be taken in the ‘qualification’ of the crowd to meet Surowiecki’s conditions of nonbias (they must understand the problem, be diverse in their perspectives, independent of groupthink tendencies and each able to bring a bit of unique knowledge to the problem, and (c) that there needs to be some incentive for people to participate in the crowd (those guessing correctly the number of jelly beans in the large jar at least win the jelly beans). The diagram above reflects these three constraints. Here’s how it works, using, as an example, a company’s problem of unsatisfactory productivity:

Let’s look at another, simpler example. Imagineers Inc. wants to know which of a new series of thirty possible products and services they should release to the market, and how to price them.

The model will even work on what Surowiecki calls co-operation problems, where there is some constraint that requires compromise by all, such as “What is the optimal salary distribution for our company?” All that’s needed to include such problems is to state clearly the constraints (e.g. total organization salary cannot exceed $X) and to not allow Qualified Crowd members to ‘vote’ on issues where they have a conflict of interest (e.g. each person can vote on everyone else’s salary but not on their own). This model isn’t limited to business applications. Non-profits have productivity problems too. In fact, of the 25 problems that most often keep executives awake at night, which I reported on in an earlier post*, most of them are challenges for organizations of every type, from government departments to NGOs to charities. Although the bigger your organization the more likely the Wisdom of Crowds is to benefit your problem-solving and decision-making, even small organizations could benefit from tapping into Collective Wisdom. Here’s just a few questions that could be posed to the ‘crowd’, just to show the diversity of applications for this model:

I’m pragmatic enough to be willing to have Collective Wisdom work initially on business problems, and continue to use such fee-paying applications to fund the enterprise. But in my heart what I really want this enterprise to do is the think-tank work, solving some of the world’s most intractable and pressing problems. I’m optimistic for two reasons: I think when it comes to solving global problems, a lot of people will be motivated to join the ‘crowd’ for altruistic reasons, and donate their time just to help make the world a better place. We don’t need to offer them a Reward Pool for such problems. And I don’t think the infrastructure of Collective Wisdom needs to be all that large and expensive. I think a few profitable, successful business pilots will be enough to get the process streamlined, the infrastructure paid for and the crowd assembled, so that we can start spending a chunk of time on solving global problems, for free. And although there may be some first-mover advantage here, I think the real value of Collective Wisdom will be in the creativity and analytical skill of its core staff and Solution Teams, and in the quality of its Qualified Crowds and implementation teams. It’s the people, not the technology, that will make or break it. There are some kinds of questions that I’m ambivalent about throwing to the crowd. In the above model, it’s the Solution Team and the customer whose imagination is tapped, not the crowd’s. I’ve assumed that giving a crowd, even a Qualified Crowd, an open-ended question like “What features would you like to see in a car, which you can’t find in any car today?” would be an invitation to anarchy. You could be reading replies to such a question for months, and end up with a completely unmanageable number of ideas, so many that you’d never be able to identify the needle in the haystack that might actually pay off in a big way. But maybe I’m a pessimist. What do you think? Could we tap in not only to the Wisdom of Crowds, but to it’s creativity as well? How could we do so in a manageable way? I think the Value Proposition for this model is compelling: Tapping into the Wisdom of Crowds with a disciplined process will reduce or eliminate the need for (and cost of) ‘expert’ consultants, academics and focus groups, while producing better decisions and solutions than those experts can offer. In the process, it can even provide manpower and investment for implementing the solutions, reducing the need for RFPs and venture capital. Business is always looking for ways to reduce cost. Not-for-profit organizations are always strapped for cash. This model works for both. That’s what I have so far. I’m getting a lot of expressions of curious interest, including some business organizations that would be willing to test the waters. I’m copying James Surowiecki on this post to see what he thinks. I’d love to know what you think. You are my wise and qualified crowd. * Here are the 25 business problems, any of which could be addressed using this model:

|

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

great article (again). Here’s a couple examples of collective wisdom at work:http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/57/lilly.htmlthe company mentioned at the end (Quovix) is my company (only now we have 1,500 in our network). InnoCentive has about 60,000 scientists who can help solve problems).The model works but not without challenges.

One very concerning problem is that The Wisdom of the Crowds is easily subverted by a single person with a strong ego looking to gain power. That person will manipulate and organize pockets of power to support his own.Why is this so?”All this was inspired by the principle – which is quite true in itself – that in the big lie there is always a certain force of credibility; because the broad masses of a nation are always more easily corrupted in the deeper strata of their emotional nature than consciously or voluntarily; and thus in the primitive simplicity of their minds they more readily fall victims to the big lie than the small lie, since they themselves often tell small lies in little matters but would be ashamed to resort to large-scale falsehoods. It would never come into their heads to fabricate colossal untruths, and they would not believe that others could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously. Even though the facts which prove this to be so may be brought clearly to their minds, they will still doubt and waver and will continue to think that there may be some other explanation. For the grossly impudent lie always leaves traces behind it, even after it has been nailed down, a fact which is known to all expert liars in this world and to all who conspire together in the art of lying. These people know only too well how to use falsehood for the basest purposes.”- Adolf Hitler

Marty,Thanks for the link to Quovix. My home is not a mile and a half from the office (Fall Creek and Shadeland). Looking for a top notch distributed computing architect?

Dale,Hey – Fall Creek And Shadeland? That’s where I live! How about a “Save The World” coffee session at Barton’s friday morning. We can debate Pollard’s ideas and maybe generate a few of our own… time to go offline for further discussion… – email is mmorrow@quovix.com

Ideology doesn’t proceed by suppression but by framing; as any pollster knows, you can strongly determine a poll’s outcome by phrasing the question a little differently. How are the specific solutions presented to the Qualified Crowd for voting going to be secured from this kind of framing? Sitting here I can imagine about twenty different ways that I could tweak outcomes by simple choice of vocabulary. That’s just the first of the who-watches-the-watchmen questions you’d face (another is how you decide who is “qualified,” and who gets to make that decision–and by the way, there doesn’t seem to be any Suroweckian diversity-and-knowledge screening for the IEM traders at all, so how does IEM count as evidence for or against his thesis? Not to mention the spotty track record your challenging commenters cite…even the linked essay about IEM says it only has a “slight edge” over polls). Dave, your enthusiasm for Wisdom-of-Crowds solutions strikes me as very “Canadian”–it doesn’t assume the degree of nihilistic corruption that’s the necessary pragmatic beginning point for thinking about any decisionmaking in U.S. business or politics.

Marty — thanks for the link, an interesting and needed ‘case study’.Dale — yes, it can easily happen, which is why Surowiecki introduces criteria for a ‘wise’ crowd, one of which is independence and freedom from the potential of ‘groupthink’TV — absolutely, which is why the Solution Team’s makeup, modus operandi, and commitment to a fair and truthful result is so critical; any kind of poll can be twisted to produce the desired result, which is why I think this will work best on problems and decisions where politics (including business politics) is not an important factor.

Good article Dave. Let me first say that I’m a (European) consultant that tries to make a living out of innovation and change in organizations. (At least that makes me one of your crowd, which in turn of course is the evidence of my wisdom.) In my daily practice I’ve been using a self-developed “technology” for over 15 years now. In retrospect, it is a mix of action research, Socratic method and -I must admit- wisdom of groups. Since my goal (or mission if you prefer) is to obtain profit for my client while improving satisfaction for the workforce (both!), my work involves a lot of surveying opinions of employees and other stakeholders. In doing so I must be very careful when formulating questions because there is an important risk of influencing the employee. So, T.V.’s remark of tweaking outcomes by use of vocabulary is very realistic and to the point. On the other hand, a company is not a democratic organisation: someone has the power based on his capital investment. So, even if my first step is to get ‘the truth on the table’ before doing anything, it is far from uncommon that the one who holds the power tries to “adjust” that truth. It is my experience that telling or selling “wisdom-of-crowds” as the ultimate procedure for sound decision-making to a CEO, is not that easy. First, because the crowd-decision may differ from his; second, because the involvement of more people invariably results in higher cost/more time. If those don’t work, there’s always the possibility of ‘not enough information’, ‘we tried that before’, or ‘priorities have changed’ as excuses. Besides, if in a company the crowds fell apart in a Bush-Kerry ratio, you’d have 48% of people that do not support the decision, and there’s nothing more dangerous than intelligent people whose opinions are discarded.Glad to hear though that you get reactions from businesses willing to “test the waters”. I think I know for a fact that -at least in Europe- it is not that easy.As for the kind of questions onecan ask the crowd, again a lot depends on how you phrase them. The rule of thumb I use in my consulting assignments is to formulate the question in such a way that it looks for the needs of the customer. The real needs. Not wants, demands or likes. (These can easily be added later on.) In this way I wouldn’t ask for what features people would like in a car that aren’t there today. Instead I’d explore what a man, a woman needs from a car. One ultimate answer could even be “I don’t need a car, I need something to get from A to B”. This information stretches the original question to a domain where the notion “car” is irrelevant. Which means that the whole question is irrelevant.See, I think a company can beat another by better understanding its customer. Christensen has described convincingly that it is not always a good strategy to keep on adding features to a product. That is because these extra features (logically) seem to make sense for the developer or marketer but they do not make sense for the customer because those features do not respond to a real need of his. That is why the average MS Excel-user apparently uses only 5 to 10% of its features. And that is why many users simply copy the thing instead of paying for it.Look at the facts: when does a successful product get obsolete? When another takes its place that clearly better matches the real need than the former. Not because it is stuffed with twice as much features the customer will not (be able to) use anyway.Finally I hope wisdom-of-crowds will not “eliminate” my firm (eliminating consultants being one of the advantages as you say). I not only hope, I don’t think so. I remain confident because I’m not exactly the ‘expert’ consultant you mean, since my expertise is in fact the expertise of facilitating and guiding a series of processes that use collective wisdom in order to result in our mission as stated above.Erwin Spriet, Belgium

It is great to see one more person realize just how general the potential for these things are. I’m most enthusiastic about the clearest cases, with clear alternatives and a clear outcome measure, but hopefully all of them will be tried eventually.