Even business is now teaching ‘observation skills’ as part of a ‘cultural anthropology’ skill set that also includes interviewing, story-gathering and story-telling, and ‘understanding that things are the way they are for a reason’ appreciation skills. Even business is now teaching ‘observation skills’ as part of a ‘cultural anthropology’ skill set that also includes interviewing, story-gathering and story-telling, and ‘understanding that things are the way they are for a reason’ appreciation skills.

Why is it that we have have to teach adults to do something that every child knows how to do from birth? Is attention deficit a learning disability we acquire as we get older, and if so, why? In business cultural anthropology, according to Conifer Research, you need to focus your attention on:

They argue that, if you interview people about their wants and needs, they will tell you what’s on the top of their consciousness, but miss the very real wants and needs that would be obvious from direct observation. But they also say you need to ask questions, through interviews, after or during observation, to understand what you’re really seeing and hearing, why it’s happening, and what could be done to make things better, instead of jumping to conclusions. In the process, the subject may learn as much as the observer. They suggest a process to map the experience of your employee or customer, as a means of archiving and focusing on improvement opportunities. Paying attention is also a recurring message of environmentalists. The celebrated environmental writer and story-teller Barry Lopez says: [My principal responsibility] is paying attention to what is going on there, so I can come home and tell a story that in some way or other is useful to the community… My life is defined largely around issues of language and story and landscape, and I would be hard pressed to separate those three issues. I think the way in which landscape is imperiled–by manipulation and attenuation to serve various political and economic policies–is almost indistinguishable from the way in which language and story are imperiled…

I first felt what we could call “a state of awe,” moments of recognizing a metaphysical dimension in landscapes, when I was six or seven years old. I remember at the Grand Canyon, in particular, when I was eight years old, being awestruck about everything that was around me, the richness–the smells, the tackiness of Ponderosa sap, the tenacity of wildflowers, those little ear tufts on the Kaibab squirrels–and spatial depth. The first mountain lion I saw was in the Grand Canyon, and it was an incident that went to the floor of my heart. Perhaps the reason we no longer pay real attention is that we no longer have much opportunity to see and hear things that inspire a “state of awe” — we are surrounded by mediocrity and sameness and efficiency and noise that exhibit no integrity, dignity, subtlety, or respect for the sacredness of life and nature. And at the same time we are constantly barraged by assaults on our senses — sights and sounds that rudely compete for our attention until we become numb to all but the loudest and most violent and most outrageous — the brightest red light, the flashiest billboard, the thinnest waist, most defined abs and largest breasts, the most provocative lyrics and videos and special effects. In an earlier post entitled Stand Still and Look Until You Really See, I suggested six exercises to practice paying attention, designed especially for the left-brain-heavy:

One of the most interesting theories about why we lose the ability to pay attention is related to the chemical dopamine, which occurs naturally in the body and is our body’s way of telling us that something we have just sensed or experienced is important and needs to be remembered. Here’s a theory from Nora Volkow, director of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse: Over time, the addict’s brain adapts to the torrent of dopamine by dampening the system down. Imaging experiments show that cocaine addicts’ brains don’t react to the things that turn on the rest of us, whether that’s romantic passion, food or cold, hard cash. Volkow’s research has also shown that addicts have fewer dopamine D2 receptors, which are found in parts of the brain involved in motivation and reward behavior. With fewer receptors, the dopamine system is desensitized, and the now-understimulated addict needs more and more of the drug to feel anything at all. Meanwhile, pathways associated with other interesting stimuli are left idle and lose strength. The prefrontal cortex–the part of the brain associated with judgment and inhibitory control–also stops functioning normally. It’s a neurological recipe for disaster. “You have enhanced motivation for the drug, and you have impaired prefrontal cortical systems. So you want the drugs pathologically, and you have reduced control of behavior, and what you’ve got is an addict,” says University of Michigan, Ann Arbor psychology professor Terry Robinson, who pioneered this new way of thinking about dopamine with his University of Michigan colleague Kent Berridge…

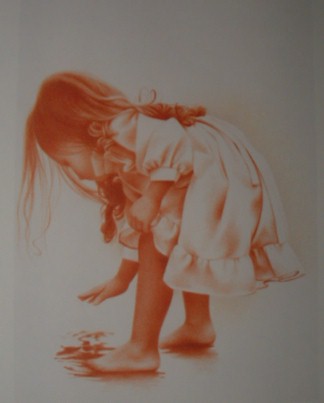

Obesity may involve similar malfunctions in the dopamine system. Volkow’s longtime Brookhaven collaborator Gene-Jack Wang has discovered that the brains of seriously obese people seem to be tuned toward food. Even when they are lying quietly in the scanning machine, the sensory cortex of their mouth, tongue and lips is more active than it is in normal-weight people, he says: “They are putting out their antennae.” Yet he also found that the dopamine circuitry of heavy people is less responsive, with fewer dopamine D2 receptors. Even among the obese, there are dopamine differences. The heaviest people in his study had fewer dopamine receptors than the lightest. Like addicts, overeaters may be compensating for a sluggish dopamine system by turning to the one thing that gets their neurons pumping. It’s a mark of changing times–and more sophisticated science–that the head of the National Institute on Drug Abuse is thinking about doughnuts as well as heroin. Are we, perhaps, all increasingly addicted to the rush of dopamine as we get older? Does the sheer constant noise and sensory barrage of messages competing for our attention eventually dull our senses to the point we cease being able to really pay attention to anything that isn’t the dopamine equivalent of a 200-decibel jet engine roar? And if so, does spending time in nature, or in meditation, help us begin to kick the dopamine habit, and open up our sensory palate to awareness we had ceased to be capable of? Are television and video games and junk food and driving in traffic and all the other high-stimulation events of modern life actually numbing us to awareness of who we are, of the importance of place and of nature, of the damage we are doing to the world, and of the messages our instincts and the rest of our Earth-organism are sending us? And if this is so, how can we overcome this addiction, especially those of us who cannot still the din by walking through nearby wilderness or refocusing through meditation? Especially those of us who really like the stimulation that the dopamine rush gives us? Are we doomed to a life of numbness, and inability to pay attention to things that are really important? Photo from my own collection. Sketch by Canadian artist Pierre Surtes. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

When I was in Orlando recently at the Disney Institute I was frequently distracted from the astonishing and brilliant details of the Disney ‘customer experience’ by wonderful natural sights that no one else seemed to notice in the Disney World of sensory overload: Baby goslings chasing insects around a lamppost, ducks in the grass enjoying the constant spray from the nearby flume roller coaster ride, squirrels perched on the top of benches staring at the parades of costumed characters with great curiosity. If I had visited there back before I moved to the country and took up nature-watching, would I have been as oblivious to these simple joys as all the people around me?

When I was in Orlando recently at the Disney Institute I was frequently distracted from the astonishing and brilliant details of the Disney ‘customer experience’ by wonderful natural sights that no one else seemed to notice in the Disney World of sensory overload: Baby goslings chasing insects around a lamppost, ducks in the grass enjoying the constant spray from the nearby flume roller coaster ride, squirrels perched on the top of benches staring at the parades of costumed characters with great curiosity. If I had visited there back before I moved to the country and took up nature-watching, would I have been as oblivious to these simple joys as all the people around me?

My understanding is that attention – to pain, joy, existence – is dynamically, on the fly, created by desire. Desire is the fundamental force of life, whether for food, procreation or ease, and is a forward movement into increasing intelligence. Thus, attention is the memetic attractor defining the evolution of intelligence.Paying attention is the ultimate sacrifice to IT, Tao, and so the highest (many puns intended)explication of our implicate Isness. Full attention is buddhaness.

A child drops her BoingBoy Machine ™ and shouts – “Daddy, I’m bored!”.Can I spend a whole evening just paying attention? What would come out of that?

Which means “Thanks, Dave”. Your post has serendipitously come my way so I may be able to help someone locally.

R. Murray Schafer’s work may answer a number of questions you’ve posed here. http://www.patria.org/arcana/arcbooks.html has a listing of his works regarding soundscapes and noise pollution as well as retraining our sense of hearing to bring about mental clarity.Next week I’ll be returning to quiet Canada after 2 years in noisy noisy Japan. One of the things I’m looking forward to the most is having my “mind space” back so I can think and write again. Thanks for the reminder.

First let me say that as a longtime reader and first time commenter, it’s a wonderful that there is a voice as strong as yours writing about these subjects. Thank you for your passion and time.I do want to point out a fact you may have over looked in this post. As a frequent visitor to Disney World and the Magic Kingdom (Florida’s version of Disneyland) I am always stopping to see the details. Both those of nature (about half of Disney World’s 40 square miles is devoted to maintaining its natural state – and Disney has spent a ton of money buying and restoring a 12,000 acre nature preserve just to the south of the property and at the head of the Florida Everglades) and design (Disney

Dave,Long time reader, first comment back here.This is an absolutely powerful piece.It’s a multi, multi-dimensional world after all, if only we can tune in on the different details.As to your last back link, namely to the “addiction” of Civilization to the things that will surely kill us. Yes this is a very important question. Surely there are readers out there who are skilled in the dark arts of redirecting public attention so that the public becomes more “tuned” to the dangers that slide us ever closer to the edge of “Collapse”.Keep up the great work.

I was just in Chicago for a weekend and even that jolt of “difference” — of seeing a city other than my own, and having no agenda, so we were able to sroll about and observe at a liesurely pace — changed the way I looked at Pittsburgh when I came home. Now I’m back to work at full-speed, and what little difference I noticed in my vacation time is gone from the immediate, but it’s always there in the subconscious. I quite enjoy being able to slow down for a little while here and there and just… observe.

Some clues here:http://www.goanimal.com/newsletters/2004/sculpt_by_cats/sculpt_by_cats.html

Thanks for the very kind comments. Some of you are clearly better practitioners of the art of paying attention than I am. John: I do know the whole story of Disney, including the natural legacy he left (though he did have his dark side) — the inability of people to see natural wonders with all the competing attention-attractors is not Disney’s fault, but the separation we have all suffered from our connectedness to the natural world, which precludes us from noticing nature. It is only recently that (due to my fortune at living in a relatively natural place) I have relearned to pay attention to it, to the point I cannot *not* pay attention to it even in the midst of noise and distraction. I am slowly becoming again a part of nature, re-belonging to it, and to not pay attention to it is as impossible as not paying attention to my own feelings, my own hunger, my own thirst. Justin, you make a good point that sometimes the best way to pay attention to what’s around you every day is to go elsewhere for a short time — the physical counterpart to meditation.