Last weekend I was watching a documentary on the Juan de Fuca Trail along the rugged west coast of Vancouver Island, BC. I used to live out on the Island so there was nothing much new to me in the program, until they described the lives of some of the squatters who have made their lives on the windswept coast, using the trail and its feeders as their connection to civilization. One of the guys they spoke to had built his ramshackle cottage entirely of windfall wood and driftwood. He had walked away from a well-paying technology job. He grows some of his own food, collects water in a rainbarrel, and makes crafts from driftwood that he sells in the closest town, several hours’ walk from where he lives, in return for additional food and small supplies. Occasionally he’ll do odd jobs if he needs something more costly. If a heavy storm destroys his house, he’ll just build it again. He’s thinking of putting up a small windmill for night light, but doesn’t miss his computer, the Internet, or TV. He has a portable radio and reads whatever books he can pick up in the town. Most of his time he spends walking the trail, meditating, and writing. He seems very much at peace. His ‘neighbours’ up the trail have several children who have grown up there, with no modern conveniences, home schooled. Their eyes are full of wonder, not the ‘caught in the headlights’ stressed-out look of so many civilized children. They seem astonishingly gentle, living in such a ‘savage’ place. Last weekend I was watching a documentary on the Juan de Fuca Trail along the rugged west coast of Vancouver Island, BC. I used to live out on the Island so there was nothing much new to me in the program, until they described the lives of some of the squatters who have made their lives on the windswept coast, using the trail and its feeders as their connection to civilization. One of the guys they spoke to had built his ramshackle cottage entirely of windfall wood and driftwood. He had walked away from a well-paying technology job. He grows some of his own food, collects water in a rainbarrel, and makes crafts from driftwood that he sells in the closest town, several hours’ walk from where he lives, in return for additional food and small supplies. Occasionally he’ll do odd jobs if he needs something more costly. If a heavy storm destroys his house, he’ll just build it again. He’s thinking of putting up a small windmill for night light, but doesn’t miss his computer, the Internet, or TV. He has a portable radio and reads whatever books he can pick up in the town. Most of his time he spends walking the trail, meditating, and writing. He seems very much at peace. His ‘neighbours’ up the trail have several children who have grown up there, with no modern conveniences, home schooled. Their eyes are full of wonder, not the ‘caught in the headlights’ stressed-out look of so many civilized children. They seem astonishingly gentle, living in such a ‘savage’ place.

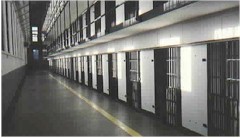

My great great great great grandfather walked away from the US in 1807, under circumstances that are not clear. Some reports say he was a Loyalist, and the lot of Loyalists in the US had not been happy since 1775 — anyone in the service of the British at the time of the Declaration of Independence, and anyone who failed to sign an oath of allegiance to the Republic and a repudiation of British citizenship was automatically guilty of treason, with loss of citizenship, seizure of all property, and prohibition from holding office (and, in some states, execution, lengthy imprisonment, or public tarring). Embittered British militias continued to fight savage battles with the new American forces until the armistice of 1814, and atrocities were committed by both sides. Some Americans made no pretense of Loyalism at all, and came up to Canada in the early 1800s simply because they were attracted by the free land grants. My guess is that Joshua Pollard was neither a Loyalist nor a Freeloader, but more likely one of the first of the great tradition of American conscientious objectors unwilling to fight in the about-to-be declared US-Canada war of 1812. He was, I would guess, a draft dodger. To get his 200 acres of land he had to come to Canada, file the petition, and wait for acreage to be surveyed and allotted. He did so, and with his wife and the first eleven of their eventual seventeen children (a normal family size in those days) squatted with many others at what is now Front and Yonge Street in Toronto, where they lived as rudimentary a life as one can imagine through three winters. Then, with two neighbouring families, they helped clear the new Middle Road to what is now the Toronto suburb of Mississauga and on each of the three families’ lots they cleared and fenced the minimum 5 acres and built the 38 x 26 foot wood frame minimum house needed to ‘own up’ to the land grant by June 1810. Life in the wilderness, a dense forest of 30-foot high trees, all done with hand tools in daylight hours. Joshua founded the first school in Peel Region — ‘cost of tuition’ was one cord of cut, stacked wood per family per semester. Nineteen people living in a 1000 square foot house, of which the 200 square foot front room served as the area’s first tavern and, one day a week, for the traveling preacher’s service and for services for the dead (Joshua also ran Peel’s first cemetery). The archival records say that, unlike the more devout neighbours, the Pollards loved to dance. My neighbours have always had two dogs, mostly golden retrievers, about six years apart in age, so that on the death of each dog, the younger sibling soon becomes the big brother or sister for a new arrival. When they first moved to our neighbourhood they installed an ‘invisible fence’ and both dogs were taught, using the ‘gentle’ setting, to stay within their three-acre lot without supervision. With the exception of one ‘slow-learning’ Bernaise puppy, the dogs have never needed a second lesson, and have never gone outside the fence — even though it is only turned ‘on’ for the first month or so after each new pup’s arrival. The rest of the time they could now wander off with impunity. In fact, the older sibling ‘shepherds’ the new puppy away from the boundary, so it is quite possible they could disconnect it permanently and the dogs would teach each other where the boundaries are. Our neighbours are wonderful, affectionate, dog-loving people, and the dogs adore them, but the power of the ‘invisible fence’ that isn’t really there at all still astonishes me. What does it take to make someone so dissatisfied, so unable to bear the life they lead, that they can walk away and start a new, better life, a different way, elsewhere? And what does it take before we realize that the prisons in which each of us live, societally and metaphorically, are prisons without locks, just waiting for us to let ourselves out? |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

“What does it take?”It’s an ethical dilemma. And you are speaking only to those aware of its existence.Most others would delineate a different prison.

Amazing post Dave. Thanks so much for sharing this.I have on several occasions “walked away” from what to me amounted to “civilization,” though my idea of that word keeps changing over the years. When I left CA for Bali 6 years ago I thought I was going off to a completely uncivilized place. I sold everything I owned and bought a one year open ticket. I arrived in Bali not knowing what town I was going to, wound up picking one by way of where the taxi seller was willing to give me a ticket to (“I’m not selling you a ticket to Batubulan. You won’t find any place to stay there. You can have a ticket to Ubud.”) and cried myself to sleep the first night, overwhelmed by the magnitude of what I had just done. It was amazingly challening, and also the greatest blessing of my life to date.After Bali I lived in NY for 2.5 years and got very comfortable there. I had a cush job with not one but 2 offices, was saving about $1000 a month (which for me is a lot), and living in a luxury high rise on the Hudson river with a doorman, tennis courts, and sailing club within walking distance. The work I was doing was meaningful and challenging and by all accounts my life looked from the outside even more ideal than it had been in CA before I left (a CA world of hot tubs, fabulous parties with a large group of brilliant, childless, high-earning friends, and music making under the moon many a night). My departure from NY, for the “wilds” of Hawaii, which I imagined to be like Bali, but is not, was preceeded by a prophetic dream. In the dream I was an angel tied up in chains and suspended above a bed of long blades pointed up at me. A voice spoke to me and said, “You believe that if you were cut free from these chains you would fall on the blades and die, but it is your comfort that has chained you. You have forgotten that it is the nature of an angel to fly.”I then awoke and the first clarity that came to my mind was, “I’m moving to Hawaii.” I will spare you the longstory of all the miracles that ensued to bring me through the transition with unbelievable blessing and ease, but it was an amazing journey that was clearly being guided at a level beyond my own intellect. And life here has been the best of my lifetime. I live much more simply than ever before, though I still have a beautiful house I pay a lot for, and I spend most of my time in close community with others, many of whom live completely off the land they live on within informal land-based communities (informal because one person generally owns the land and lets others build on it or he builds and trades living space for gardening, etc.).It isn’t exactly homesteading here in HI. This is America afterall. But it is a far cry from the life I once knew. My encouragement to anyone thinking of starting over is, if you feel the call, answer it. Don’t let your comfort chain you any longer.