The gist of the Tragedy of the Commons, for those who haven’t read my blatherings about it before, is that when people own something personally they take care of it, but when no one owns it, when it’s a shared resource, like forests and parks and public toilets and recreation centres, nobody takes care of it, and it becomes the victim of the more talentless graffiti artists and litterers and vandals and pyromaniacs and guys who pee on toilet seats. The gist of the Tragedy of the Commons, for those who haven’t read my blatherings about it before, is that when people own something personally they take care of it, but when no one owns it, when it’s a shared resource, like forests and parks and public toilets and recreation centres, nobody takes care of it, and it becomes the victim of the more talentless graffiti artists and litterers and vandals and pyromaniacs and guys who pee on toilet seats.

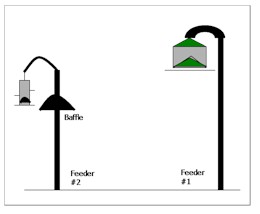

So I got thinking about whether this contemptible and careless ‘commons’ behaviour is something uniquely human, especially since I have yet to find any behaviour of any kind that is uniquely human, and don’t expect to. In a way, all of nature is a ‘commons’ to the rest of the species on this planet. Yet other creatures don’t damage and destroy common areas. And then I realized that these natural commons have something that human commons don’t — abundance. What human commons have in, er, common, is that they are all scarce, all set aside specifically as common spaces, in the midst of areas that are ‘private’ (‘private’ spaces being those that are arrogantly assume to be the property of some human to do whatever he wants to do with them regardless of the consequences). A much better analogy to human commons is the bird feeder, that (relatively) scarce and unnatural commodity that some of us who love watching other creatures set up for their, and our, communal benefit. At bird feeders you can see non-human creatures treating a common resource the way we humans do. Squirrels can literally demolish most bird feeders in a week. You put up a squirrel ‘baffle’ and they’ll dedicate their full diligence to defeating it. After all, why would you put out food just for birds? That’s not fair, is it? And why would you put out food just a bit in dribs and drabs, and keep the rest in a metal can? We squirrels have been managing fluctuating food resources since before you bipods appeared on the planet — just put it all out there and we’ll figure out what to do with it. The black squirrels have now figured out how to get around my baffle even though it’s six feet above the ground (beyond their jumping range) and on a pivot so they can’t stand on it even if they can get past it. They have their own baffle-less feeder ten feet away (feeder #1 in the above diagram). The food in it is accessible to all, and disappears in 24 hours from time of filling (every 2 days in winter, every 3 days in summer). So it is more often empty than not. Feeder #2 has a cylindrical container and perches designed for the smaller birds that tend to get bullied out of feeder #1 one by squirrels, chipmunks and the larger birds like grackles and redwing blackbirds. The process for a squirrel to get into feeder #2 took a lot of experiment and ingenuity, but now takes them about 5 seconds:

The chipmunks are not big enough to manage any of this, so they study where I keep the seed. I have tried keeping the seed in the garage, but they’ve found openings under the eaves and eaten holes in the bags when I leave them there. Now I keep it in the sunroom, in a large aluminum can. They’ve chewed holes in the sunroom screens to get into the room, and last week I caught one, obviously a keen observer, sitting on the aluminum can, making a hell of a racket trying to pry the spring-clip up. In the winter, ornithologists believe, chickadees, sparrows and some other small birds actually do depend at certain times on the food in bird feeders (they need to bulk up by evening to survive the coldest nights, using the food energy to ‘shiver’ vigorously to keep their body temperature up). They usually leave plenty of room for error (many creatures have three winter choices — migration, hibernation and bulking up — and generally the number that choose the third option is small enough that they don’t have to worry about shortages), so birds freezing to death are rare. Nonetheless, these small birds would clearly be more conscious of the value of using up bird feeder resources carefully. So I was amazed to discover that the chickadees, at least, conserve the seed in feeder #2 (subject to interference from other birds and squirrels), to last exactly the two or three days between fill-ups. Right after I fill it, the chickadees rarely take seed from feeder #2 (they use feeder #1 when available first, and even then eat at the feeders sparingly — I presume they are busy feeding elsewhere. At the end of the second day in winter, third day in summer, when it is getting low, they are there in large numbers, and the bottom half of the cylinder is consumed in a matter of a few hours. If I’m late the next morning, I get a scolding (at least that’s what it sounds like) from them, but once it’s filled they tend to take one seed each and then disappear for most of that first day. It seems to me that, much like humans planning our gasoline tank refills, these birds are conserving. While to most species the feeder is just a bonanza, a ‘commons’ to be plundered and abandoned, to the birds that may depend on it, it is factored into the overall food supply and managed accordingly, as if it were part of the natural supply. Perhaps I am reading more into this than I should, but despite the disruptions by the squirrels I can generally tell the day (feeder refilling day, second day, or third day) and the time, by how much seed remains in the cylinder. And when I switch between the winter (every second day) and summer (every third day) filling schedule, it takes less than a week for the birds’ usage pattern to adapt so that feeder #2 is empty just before it is scheduled to be refilled. So I am tempted to speculate that conservation, ‘resource management’, is not natural, because it is unnecessary in a world of abundance. It is only when there is some scarcity that creatures like humans and chickadees adapt to conserve. It is not natural behaviour for us, either — for most of our three million years we have migrated long before the foods we gathered became scarce (we also, like virtually every other creature on the planet, instinctively reduced our birth rate so that our numbers were stable and so we almost never faced scarcity — by the time the last stop in our migration began to run low on human food, the first stop had been fully replenished). So it is probably not surprising that a conservation ethic doesn’t come easily to us. The bird feeder, in this context, is a bit of a sad place. It brings out selfish and destructive behaviour in creatures that don’t quite understand what this strange, inexplicable cornucopia is for. Perhaps it’s not dissimilar in that sense to the antisocial and self-destructive behaviour that seems so often to come out in those who win lotteries or receive sudden great wealth or fame. And the bird feeder reflects how the Tragedy of the Commons arises, not because we are incapable of sharing and taking responsibility, but because when commons are scarce and strange, instead of ubiquitous and sacred, most creatures seem driven to take advantage of them, and assume they will not last. The real tragedy of the commons is that when we invented ‘private’ property, we forgot that the whole universe is a commons that belongs to all life in it, and we lost respect for it. Scarce, limited ‘commons’ are unnatural aberrations that we just cannot make sense of. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Here’s an interesting editorial in today’s NYT that’s in the same vein to this article.

On the subject of tragedy of the commons — I’ve always considered dog poop a classic example of this tragedy. People won’t pick up their dogs’ poop on the walking trails in our neighborhood, even though these piles of poop makes **their own** walking experience less pleasant!

i disagree, dave. the whole world is not a commons. not to most beings. it’s turf and territory and defended aggressively from others. that squirrel isn’t scooping only his share, he’s taking as much as he can of that seed. it’s not squirrelly philanthropy to scoop a bunch extra for other, less agile, squirrels to eat off the ground later. it’s just eating whatever you can find. if you can get it, it’s yours. walk too close to a bird nest full of eggs and you’ll find private property rights being strictly enforced via sharp diving pecks to the head. it’s all private property. commons are a very new development. and the folks you’re talking about who wreck them in various ways are merely slow on the uptake. most of them just don’t realize any value, don’t realize the commons, have yet to become aware that they benefit from others actions. so they experience no loss, no tragedy when they mess up somethign that was kindly left for them by others. it’s not so much the scarcity of commons as the scarctiy of appreciation and u;nderstanding of what they are, because they are very new, rather than very old.

This account of the chickadees’ use of feeders in the winter rings a bell with me: it has struck me that the bottom half goes more quickly than the top. This winter I’ll be paying more attention. Interesting post. Thanks!

Conservation is either a very old idea or a very new one, but nonetheless, one that has adapted to our times. In Ojibway, the word ‘debiziwinan’ means both ‘abundance’ and ‘sufficiency’.

How did squirrels get around your baffle on feeder #1?