Lately I’ve come to the realization that the problem of under-use and misuse of information has little to do with technology or ‘knowledge management’ and a great deal to do with human nature and culture. Lately I’ve come to the realization that the problem of under-use and misuse of information has little to do with technology or ‘knowledge management’ and a great deal to do with human nature and culture.

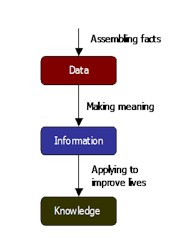

I use the definitions of data, information and knowledge shown at right. Information means literally “to put form to” and knowledge comes from the same root as the word “cunning” which suggests application, not collection. So, for example, laboratory sample results are data, a theory of the cause of a disease stemming from that data is information, and a vaccine for the disease is knowledge. Another example: Test scores of grade three students are data, an analysis of the learning needs of those students is information, and the resultant learning curriculum is knowledge. For the most part science and art are in the ‘sense-making’ business and their product is models, information, representations of reality, yielding products that are interesting and sometime useful. Most modern organizations are in the ‘application’ business, using information to create technologies (in the broad sense of the term) designed to improve people’s lives. Whether most technologies actually do make the lives of people better (other than their owners’ management and shareholders) is of course open to debate. I spent much of my last year, as global Knowledge Innovation leader at a major professional services firm, looking at what I call ‘information behaviours’, and I concluded that what impedes the sharing of information in most organizations is our personal and shared culture, rather than inadequacies in technology, knowledge management, or learning programs. Here are the cultural factors that, I would hypothesize, cause most ‘knowledge failures’:

What have I missed? What other ‘information behaviours’ are at work making it easier, or harder, for people to share what they know with others? With all these psychological barriers to the sharing of information, sometimes it’s surprising that the people, especially in large organizations, are able to communicate with each other at all. So what can we do? In a follow-up to this post I will explore some of the techniques that are, or might be, used by organizations to ‘work around’ these impediments to learning and sharing of knowledge. But we can’t expect technology to do the heavy lifting here. In fact, over-engineered tools can actually make the problems worse. And behaviour can be extremely difficult to change — people behave the way they do for a reason. More effective workarounds might include:

What other techniques have you found that help overcome the many behavioural obstacles to the sharing of information? |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Wonderful post, Dave. You’ve opened my eyes to a few things I was aware of but had not considered seriously, before reading your post. Esp. #3. I guess it depends on whether the person with access to the information is logical/creative. a logical and practical person might want to reuse while a creative person might want to do it herself despite the perceived loss of time and effort… I have a related post on my blog….http://nirmala-km.blogspot.com/2005/02/km-culture.html

One of your best Dave! This was a total eye-opener and I had lots of “Aha!” moments reading the various constricts to information sharing (and gathering).I’m not sure the people part of this dilemma can be really changed par se as we all operate from positions of protecting our tribal/individual status quo – that’s just human nature: but as the sheer volume of information grows exponentially, there will be some sort of paradigm shift in company strategies to make sifting the important information from the flotsam more efficient.Some companies will become militant and extremely focused in controlling access to their knowledge (large multi-national agri-chemical companies already are) these companies will be recalcitrant about ANY knowlege sharing, charging for the “privilege” of anyone wanting to understand anything etc.Other companies will appear to break-apart into smaller and more maleable sections of the same business which will then be more able to shift and change quickly to new data,information and knowlege growth. I also see the growth of the micro-mini business. That is, businesses made up of 1-6 people. These micro-businesses will stay small deliberately, not only to keep costs down but also to keep their structures super flat and the flow of information more immediate and effective and to maintain communal integrity in their relationship with the consumer public. Information Management may also become a new career option for many as the ability to assess, collect, define and maintain information that is relevant and USEFUL to a company will be a major asset to that company’s ability to be effective.GTD as a University Degree could well be on the cards!!!Mitch

Here is a suggested reading related to the possible solutions for knowledge sharing.It’s a David Weinberger’s article about KM at the BBC.http://www.kmworld.com/publications/magazine/index.cfm?action=readarticle&article_id=2224&publication_id=142

#’s 1, 2, 10 and maybe 11 might be addressable by some sort of anonymous information gathering/sharing systems (like an internal company message board, with polls, idea posts, etc.). If the system could assure anonymity and a level of decency (no “president sucks!” posts – maybe moderated), then people would feel free to mention certain problems which could in turn be viewed by all levels of the company and maybe its customers/vendors. as far as 13, 14 and 16, maybe this anonymous system could issue some sort of ID# for posting an idea/solution, etc. If the solution/idea works, then management can credit and reward whoever owns that ID# (or maybe a collection of id#’s) with a bonus (if they are willing to come forward). Just thinking out loud here. Great post.

OK, I swear I hadn’t read that article that Vincent posted before my previous comment. So yeah, basically what the BBC is doing, but anonymous and with a reward system. You must think me a hack!

I follow these posts every morning and the constant level of investment you make in this blog is astonishing. I’m just going to make a bit of “left-field comment” with regards getting people to share. In my experience the real “deep share” only occurs where people are “realy excited”, where there is an energy and excitement that yes, we are going for innovation that changes the way things work, not just around here, but anywhere. I have worked mostly in small, innovative high-tech environments, so that must kind of atmosphere has to be the air we breath. The “how to” is captured well in the points above, I guess I’m just saying that the “why” needs to be in there as well. Keep up the good work.

You forgot to mention the instituting of a reward system for those who originate new ideas, disseminate the ideas to others, or educate others about the new ideas.”They who are in charge” of corporate America (or Canada or other Adam-Smithian societies) insist on getting rewards for their alleged “risk-taking” activities and their alleged “leadership” activities.In other words, the neo-BS men maniupulate others into always giving to “them who are in power” because they claim we live in an “ownership” society. So where is all this generous giving when the flow is the other way? An honest corporate society should instututionalize an internal patent rights and copyrights and educate-rights system that rewards those within the organization who engage in valuable originating of new ideas, disseminating of the ideas to others, and educating of others. If they refuse to do so, they are one way hypocrites.

We have an enormous problem with sharing information in the publishing industry, especially among writers. The average published author refuses to share data about income, contracts, approaches to self-promotion and publisher relations likely because they fear losing status, being dropped by a publisher or giving free advantage to the competition, which is basically every other writer out there.I’ve tried using humor and/or the direct approach to sharing info about all aspects of my seven years of experience working in the industry over the last year, and the results were a mixed bag. My candor has offended many pros and caused resentment among less-established writers, but I’ve gotten raves from unpublished writers who couldn’t find the information anywhere else.It doesn’t hurt that I’m an established writer, and my backlist gives me a certain amount of clout and protection. If you’re at a point in your career where you depend heavily on the goodwill of peers and superiors for your future success, I think it’s best to go carefully.

Great post Dave, and thanks for it. I’ll add a few observations of my own about information sharing:1) The degree to which people share information corresponds to their awareness that power can derive from sharing rather than witholding.2) People are far more likely to act on conclusions that they draw from the information they receive, rather than on someone else’s conclusions. This is why executive PowerPoint presentations usually have no effect whatsoever.3) In the abscence of information about something important to a group of people, they will make up their own story. More often than not, the story that they make up is worse than the truth.

A counterfactual to 12 “People don’t take care of shared information resources” is wikipedia.What is different about that project (which has some reputation points of Open Source projects, but none of the articles have lead authors, so it doesn’t track directly to OS projects)?There are some commons which are not tragic, and wikipeda and successful Open Source projects are an example.

Vincent, thanks much for the BBC link. There are some good and subtle things there – and it sounds very real, having had the chance to consult there a while once.Clive

Damn, another fantastic post, deserving of a blog unto itself, and yet already there’s a new essay up.

>> eliminating reward and performance evaluation processes that encourage people to hoard or fight over credit for information and ideas, or interfere with collaborationWhat do you find makes a good reward process?

This is an excellent article. Many times we confuse information with power, power in the sense that if we hold onto it, we’ll have greater power. Unfortunately, it is the sharing of information that leads to a greater influence on the world. One other interesting caveat of this is the fact that we’re living in a “remix” period. People are taking old things (even information) and remixing it with new ideas and new forms of communication. Within this period, the lines of information ownership are becoming blurred.

This is a great article that really defines what I was talking through in my latest blog post on <ahref=”http://blog.brettmoller.com/?p=44″> CMS V Blogging and the sharing of good information in relation to effective teaching practice. Thanks for the great insight into information sharing and colaboration!! Great stuff…..

Thanks for your excellent post Dave. All your behaviours resonated with my experience. Your list prompted me to think of a few others you might like to consider:- people have no idea that someone else might be interested in what they know (they don’t value their own knowledge) and conversely they have no idea of what other people know that might interest them.- people feel busy and don’t feel they have the time to share their knowledge- people only absorb information which they need now while most information arrives when it is not needed.- information is typically only packaged in one way and the way it’s packaged don’t resonate with the receiver.- people stay in their discipline and just reinforce their current thinking.

Thanks, everyone. This post has generated a lot more buzz than I expected. Since I’m giving a speech on this next week, I really appreciate the feedback, additional ideas and links. More to come on this soon.

you forgot the money dimension. turns out people will go with information they paid for even if they can get better information from their own people. tthus the existence of the consulting industry.

doh – i need to include this link:http://www.bazaarz.com/archives/2005/09/the_consulting.php

This is an extremely well-thought out article. I’d just like to add the notion that people are more receptive to information if that information helps to confirm their belief in a predictable world. It’s extremely threatening to perceive the world as anything but predictable, which I tried to say in a succinct way in this song:Predictabilitywords and music by Dr. Bruce L. Thiessen, aka Dr. BLT (c)2006http://www.drblt.net/music/predict.mp3Bruceaka Dr. BLTThe World’s First Blog n Roll Artist