Last week, consumer product giant Johnson & Johnson paid drug giant Pfizer $11B for a whole bunch of brand names, for products all available in much cheaper generic formulations. What hope do sustainable, responsible entrepreneurial firms, and ‘buy local’ programs have, when the oligopolies hold such sway over the consumer that the mere names Listerine, Visine, Sudafed, Nicorette and Lubriderm will compel them to pay billions more for the concoctions bearing them than they will pay for natural, simple formulations? Most of the people I know pay premiums as high as 300% for such brands, for three main reasons:

The first reason is largely fallacious thinking. The main reason these brands are ‘still around’ is due to the money invested blanketing big retailers’ store shelves and the airwaves. They pay retailers not to carry competing products. All the money they spend on ‘new improved’ versions and rebrandings is merely to give you the illusion of real choice, to protect their brands. There are, of course, some poor-quality generics, and a single experience with a poor no-name product is likely enough to put you off generics for a long time, and convince you that ‘only poor people who have no choice’ would buy no-name products (though a recent study shows the poor are even more likely to buy more expensive brand names than the rich). A real cynic would wonder whether these poor-quality products are deliberately and anonymously produced by the oligopolies for exactly that purpose. In some cases, the purchase of brand is to impress others, to convey status or perceived quality. This is particularly true in clothing purchases, though restaurants also insist on carrying brand names (Coke; HP sauce) when they are visible to customers. The third reason is also illusory. The oligopolies have very sophisticated systems in place to protect them from any risks to their shareholders. Lots of people have tried to sue them; very few have succeeded, and some of them have been countersued and bankrupted by the oligopolies’ armies of well-paid lawyers. The corporatist argument that ‘frivolous litigation’ by consumers is out of control is, as I’ve reported before, complete nonsense, propaganda to bully politicians into making it even harder for injured consumers to receive fair treatment. (Most product-related lawsuits are in fact launched by corporations against other corporations, usually for alleged intellectual property law violations). When a company is so irresponsible that its product unarguably and grievously injures the public, the corporation usually goes bankrupt, the victims each get little or nothing, and the ultimate parent, protected by its ‘limited liability’, just shrugs and goes on with its business. The only reason that makes any real sense is the second. In Canada, there is a very popular generic brand (of just about everything) called ‘President’s Choice’. Launched by the Loblaws grocery chain (Canada’s largest) as a mid-price alternative between brand name and its own no-name products*, and now independent and sold by several retailers, ‘PC’ products generally try to imitate brand names (in colour, consistency, and sometimes even packaging) as much as possible. Ironically, they are often produced by the same manufacturers as the brand names. They have been successful to the point they are now actually preferred over the brand names by a lot of customers. Once you get used to a certain product, even if it’s a generic, you don’t want to change. You find the alternative less appealing. In his book The Shangri-La Diet, Seth Roberts explains this phenomenon as, at root, biological. In nature, the young learn what is safe to ingest by watching their parents and smelling their breath — only familiar-smelling and familiar-looking foods are eaten. This preference for the familiar is Darwinian — eat those lovely-looking but unfamiliar poison berries and you’re removed from the gene pool. Nature, Seth tells us, reinforces this by actually getting us craving the exact formulations (that have caloric ‘value’) we’re most familiar with. Your body in fact tells you “If it’s not Heinz, it’s not ketchup”. Seth shows that by switching to less familiar flavour combinations you can wean yourself off these cravings and lose weight. Although this Darwinian preference for precise familiar formulations only applies physically to products we ingest, it is likely that psychologically the same preference for the familiar holds for other kinds of products like Band-Aid and Sudafed. Reinforce that with the (mis-)perception of higher quality and responsibility of these familiar brands, and you have a collection of names worth $11B in an oligopoly trade. So what if you’re an entrepreneur, with a healthier, natural, more innovative product, and you’re up against J&J in your local market? If you’ve followed the ‘find a need and fill it’ process I’ve outlined in The Natural Enterprise, you will have created three competitive advantages of your own to offset the three ‘established brand’ advantages bulleted above:

In fact, these advantages trump the ‘established brand’ advantages:

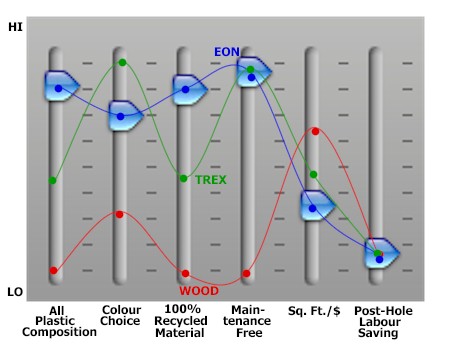

An in case this isn’t enough to overcome the oligopolies’ incumbency, at least in your community, I have a couple of additional ideas. The first idea is a federation of entrepreneurs with a mutual certification process and a single meta-brand. You’ve probably heard of the Good Housekeeping magazine Seal, which for years helped the big oligopolies enhance the illusory perception of responsibility. It was simple: (a) the corporation had to place a certain amount of advertising with the magazine, (b) consumers could send the magazine unsatisfactory products bearing the Seal for two years after purchase and get a full refund, (c) the corporation indemnified the magazine for these refund costs. What I’m talking about is something similar, but with substance: (a) the meta-brand would only be available to local sustainable enterprises (LSEs), (b) collectively the LSEs would conduct quality tests on all members’ products, and monitor customer ratings and complaints, and only allow the meta-brand on products that passed the tests and had high customer ratings, and (c) the LSEs would accept no money for doing this — participation in the collective process of testing other LSEs’ products and helping monitor customer ratings would be a collective process, a part of the cost of doing business. It would be a cellular organization — in each local community, LSEs would test and monitor each others’ products (as customers themselves), and help provide global oversight to ensure the integrity of the process in other communities. With their own products’ reputation in their own community at stake (a hugely valuable asset), LSEs would be very unlikely to collude with others to lower the value of the meta-brand. The meta-brand, all by itself, would lower customers’ resistance to switching from an incumbent’s product — the customer would know it’s been tested, and peer-approved, and that it was locally and sustainably produced. But — and here’s my second idea — you could nudge them to switch even more strongly if, right under the brand, you listed the differentiating factor, the need that the incumbent’s product doesn’t adequately fill or doesn’t fill at all. That way you leverage both your ‘better mousetrap’ and ‘better knowledge’ advantage to those customers who have not yet discovered it. You could even show those differentiating factory graphically by putting an equalizer, like the one pictured above, right on your product label. You’ve done your homework, you know what need your product fills that your competitors’ don’t, and why — why not be explicit about it? It could give the term ‘equalizer’ a whole new meaning for a new generation of LSEs. Like yours. *Retailers, in fact, would prefer you to buy their ‘store brands’, which, despite their lower price, carry a higher profit margin to the retailer. That’s because the trillions that big corporations spend promoting and advertising these brands get passed along to the retailer, who of course passes thesecosts on to you. Big Pharma alone spends $60B per year on advertising and promotion, which kinda puts the Buffett donation in perspective, doesn’t it? |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites