| This is an article I prepared for the newsletter of the World Innovation Foundation and it is addressed to the Foundation’s members, who are substantially Nobel-winning scientists. Regular readers of HtStW will find the first half covers familiar territory, and may want to skip to the part following the second diagram.

But the scientists have been much slower in bringing to collective consciousness the fact that global warming is just one of a complex series of phenomena that, taken together, threaten to accelerate that extinction a thousand-fold and bring our current civilization to an abrupt end. This reluctance is perhaps understandable when most of these other phenomena are not principally scientific: The End of Oil is an economic phenomenon as much as a geological one. The availability of knowledge that allows small stateless extremist groups to manufacture and unleash devastating chemical, biological, genetic and nuclear weapons is a sociological phenomenon as much as it is a technological one. The threat of a second Great Depression due to reckless and unprecedented debt and trade deficit accumulation is a political and economic phenomenon. The threat of epidemic diseases caused by the enormous concentration and global movement of human and animal bodies is a phenomenon that, if our response to SARS is any indication, is a phenomenon that no one is capable of grasping or addressing, since it is at once scientific, social, economic and political. The threat of massive famine due to grotesque exhaustion of our ecosystems, staggering overpopulation, fragile and unsustainable agricultural processes, and lack of diversity of agricultural ëproductsí is similarly multi-faceted. We are so preoccupied with coping with impending oil shortages that we have not even begun grappling with the huge water and other resource shortages that our world faces in the coming decades, and the political and economic (and probably military) fallout they will probably produce. And meanwhile civil and regional wars of a more familiar sort grow ever larger and more dangerous as inequality of wealth, income, power and opportunity spiral ever higher and as technology gives us ever more effective ways to wreak havoc and enduring damage on each other and our environments. The term coined to describe the confluence of these crises is ëthe perfect stormí. But that term suggests a million-to-one-shot, and fails to recognize that human and ecological systems are inherently complex, adaptive systems. As a result, these systems are largely unknowable ñ to the delight and consternation of scientists and other students of such systems they have more variables than can ever be quantified, analyzed or projected. All we can do is influence them in hopeful ways, try to understand them a little better, and marvel at the fact that they work in ways we can never fully grasp or control. Recent ‘cultural studies’ of such systems, and of the lessons of history, have suggested to those who attempt to look at them holistically that the problem we face today is not the freakish ëperfect stormí but rather the cascading effect of crises as one system after another peaks and crashes, as such systems always and naturally do. At the dawn of this brave new century we are stretched to the limit in our ability to deal with all of the phenomena described above. These phenomena exert ‘tectonic stresses’ upon our social and ecological systems, and as these interconnected systems begin to peak, rupture and crash in this century, the result will be a series of cascading catastrophes, the combination of which will cause our culture to crumble. The award-winning University of Toronto professor Thomas Homer-Dixon, in his new book The Upside of Down, based on the work of Buzz Holling and Joe Tainter, calls this phenomenon of cascading catastrophes ëpanarchyí. The consequence for any civilization of panarchy is collapse, and for ours this collapse could occur quite conceivably in the latter part of this century. A decade ago, such a view would have been considered extreme, even Malthusian. But hardly a week goes by now without the release of yet another book describing, in increasingly compelling terms, the fragility of our social and ecological systems, their lack of resilience, and, most importantly, the complex interrelationship between all of these systems, such that a breakdown of one can easily produce a breakdown of the others. In his book Straw Dogs, philosopher John Gray says that we have long passed the point of being able to ësave the worldí and prevent our civilization from collapse: Humanism can mean many things, but for us it means belief in progress. To believe in progress is to believe that, by using the new powers given to us by growing scientific knowledge, humans can free themselves from the limits that frame the lives of other animals. This is the hope of nearly everybody nowadays, but it is groundless. Humanists insist that by using our knowledge we can control our environment and flourish as never before — a secular version of Christianity’s most dubious promise that salvation is open to all.

James Lovelock has written: Humans on the Earth behave in some ways like a pathological organism, or like the cells of a tumour or neoplasm. We have grown in numbers and disturbance to Gaia, to the point where our presence is perceptively disturbing…the human species is now so numerous as to constitute a serious planetary malady. Gaia is suffering from disseminated primatemaia, a plague of people.

A human population of approaching 8 billion can be maintained only by desolating the Earth. If wild habitat is given over to human cultivation and habitation, if rainforests can be turned into green deserts, if genetic engineering enables ever-higher yields to be extorted from the thinning soils — then humans will have created for themselves a new geological era, the Eremozoic, the Era of Solitude, in which little remains on the Earth but themselves and the prosthetic environment that keeps them ‘alive’.

[Quoting Reg Morrison, The Spirit in the Gene] If the human plague is really as normal as it looks, then the collapse curve should mirror the growth curve. This means the bulk of the collapse will not take much longer than 100 years, and by 2150 the biosphere should be safely back to its preplague population of Homo Sapiens — somewhere between a half and one billion.

Climate change may be a mechanism through which the planet eases its human burden…[or] new patterns of disease could trim the human population…War could have a major impact…weapons of mass destruction — notably biological and (soon) genetic weapons, more fearsome than before…It is not the number of states that makes this technology ungovernable. It is technology itself. The ability to design new viruses for use in genocidal weapons does not require enormous resources of money, plant or equipment…In part, governments have created this situation. By ceding so much control over new technology to the marketplace, they have colluded in their own powerlessness.

If anything about the present century is certain, it is that the power conferred on ‘humanity’ by new technologies will be used to commit atrocious crimes against it. If it becomes possible to clone human beings, soldiers will be bred in whom normal human emotions are stunted or absent. Genetic engineering may enable centuries-old diseases to be eradicated. At the same time, it is likely to be the technology of choice in future genocides. Those who ignore the destructive potential of new technologies can only do so because they ignore history. Pogroms are as old as Christendom; but without railways, the telegraph and poison gas there could have been no Holocaust. There have always been tyrannies, but without modern means of transport and communication, Stalin and Mao could not have built their gulags. Humanity’s worst crimes were made possible only by modern technology.

The mass of mankind is ruled not by its own intermittent moral sensations, still less by self-interest, but by the needs of the moment. It seems fated to wreck the balance of life on Earth — and thereby to be the agent of its own destructionÖ Humans use what they know to meet their most urgent needs — even if the result is ruin. When times are desperate they act to protect their offspring, to revenge themselves on enemies, or simply to give vent to their feelings. These are not flaws that can be remedied. Science cannot be used to reshape humankind in a more rational mold. The upshot of scientific inquiry is that humans cannot be other than irrational.

[Referring to the ancient Chinese ritual of creating, worshiping and then discarding straw dogs] If humans disturb the balance of Earth they will be trampled on and tossed aside. Critics of Gaia theory say they reject it because it is ‘unscientific’. The truth is that they fear and hate it because it means that humans can never be other than straw dogs.

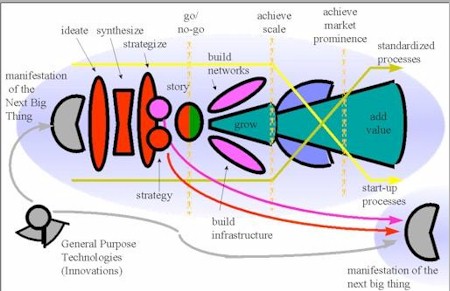

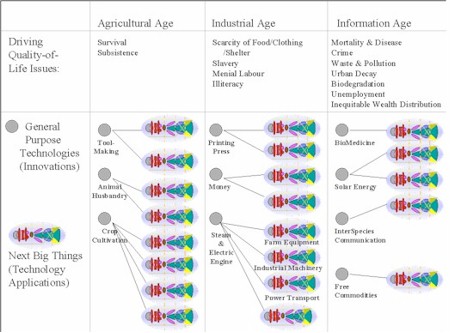

This is indeed a grim picture, but Gray insists he is a realist, not a pessimist. He urges us to do nothing other than becoming more our animal selves — reconnecting with the rest of life on Earth and with our primeval senses and instincts, getting outside our heads, coping with contingencies, relearning to play, living in the moment, turning back to real, mortal things, and simply seeing what is. I think Grayís diagnosis is probably as accurate as any diagnosis of a complex adaptive system can be. I would argue, however, that it is just not in our nature to accept the inevitability of the collapse of civilizations. More than that, I think it is our nature as human beings to accept and act on our responsibility to do what we can to rectify the harm we have done and to make life better for those who will survive the collapse of civilization and who will have to build the society that follows it. That sense of responsibility is, I believe, a universal human trait: Oren Lyons, the Onondaga Faithkeeper, whose culture predates the predominant one of today by centuries, says in a recent interview by Barry Lopez for Orion Magazine: ìOf, by, and for the people. You choose your own leaders. You put ’em up, and you take ’em down. But you, the people, are responsible. You’re responsible for your life; you’re responsible for everything.î For most of my adult life, I have been a student of innovation, and innovation is the means by which I, and I think most scientists and entrepreneurs and technologists, seek to exercise that responsibility and make this world, now and for the future, a better place. This is why weíre here, and the task at hand has never been more challenging or more urgent. So what do we do? In a world in which innovation is hemmed in by risk aversion, by intellectual property law, and by the human disinclination to change until there is no other choice, what can we do to bring innovation to bear to make the crash of civilization as soft as possible and to prepare those who will outlive it to start again with the best tools and models and knowledge our ingenuity can give them? Back in 1999, Credit Suisse First Boston ran a New Economy Forum which produced a model of the innovation process in business, diagrammed above: In a paper I wrote a few years ago I applied this model to the way in which innovation has addressed basic human needs in past ages of our civilization, and is in the process of doing so to address the pressing human issues of today: chronic and epidemic disease, crime and terrorism, waste and pollution (including global warming), urban decay, famine, overpopulation, biodegradation and ecosystem exhaustion, unemployment, inequity, scarcity of critical resources, loss of biodiversity, economic overextension and unsustainability, chronic violence and war: In each age of our civilization, however, the scale, complexity and interconnectedness of these issues have grown exponentially. Innovations and interventions that address one of these issues are increasingly inadequate as each new focused solution ignores or even exacerbates (by introducing new threats, vulnerabilities, wastes and opportunities for misuse) other and new problems. Increasingly, too, the economic system that was designed to introduce and scale innovations has become antithetical to innovation: It is cheaper and less risky for a corporation to buy (or buy out and suppress) an innovation than to develop one itself. Many ëinnovativeí startups are conceived purely for an early sellout to a large corporation often disinclined to introduce it when it threatens its existing brand. Intellectual property laws in many countries allow and encourage the patenting of entire processes and the intimidation, by armies of lawyers, of entrepreneurs who encroach on any aspect of those processes. And corporations are rewarded for schemes that enable them to circumvent social and environmental laws to ëcompetitive advantageí, and now arguably spend more energy trying to defeat regulations that were designed for the public good than they spend on initiatives that serve the public good. So it seems to me that the innovation model that worked in the industrial era is no longer serving us in this new and more complex era, and a new model is needed. What might this new model look like? I believe it must have the following attributes:

So that is my challenge to you, representatives of the worldís brightest scientists and most accomplished and creative thinkers. Let us start now, with a sense of urgency and shared purpose, to invent the future, one that will reach beyond and outlive the collapse of our civilization. Ronald Wright, in his book A Short History of Progress, summarizes our human destiny by saying ìIt’s entirely up to us. If we fail — if we blow up or degrade the biosphere so it can no longer sustain us — nature will merely shrug and conclude that letting apes run the laboratory was fun for a while but in the end a bad idea.î Letís show Mr. Wright and Mr. Gray that the apes still have a trick ortwo up their sleeves. Categories: Prescription: How to Save the World, and Innovation and Society

|

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

yes .. and with our language and perception skills we hairless apes should engage in more and regular serio ludere

I was just reading about the release of apples new phone, and the coming iTV.As always, you bring me back to earth with the real issues of today. How can we use technology, and more importantly, others to create a new way. I hope things don’t collapse, that might be optimistic.I hope we can leave behind some lessons, and that is exciting.

I read Mr. Gray’s book, as well as Lewis Mumford’s epic “Pentagon of Power”. Both are formidable diatribes skewering the anthropocentric windmill. Your analysis is spot on Mr. Pollard, although none of your solutions are even remotely possible without new ways of thinking. Hence, I would elevate #6 to the primal spot. Alas, given the stranglehold consumption has on communication, I fear the only way minds will change is through catastrophe. Kind of like a Gaia “New Pearl Harbor” making our mantra “do no harm”.

Jon/P{at/RJ: Excellent thinking. This of course brings us back to the quandary: To wait for the catastrophe will be waiting until it’s too late; to precipitate it is immoral. The narrow and difficult midground is convincing the world that the catastrophe is already upon us.