consensus flowchart by tree bressen In our modern society, there are five distinct ways that decisions get made. Each entails power dynamics, and make no mistake: Decision-making is all about the exercise of power. Here’s a snapshot:

There is evidence that, prior to the advent of civilization and overcrowding, when resources were abundant and accessable to all, society was largely anarchic: that is, individuals (even within tribes) made their own decisions and lived with the consequences. At the local level in anarchic societies, with no regulatory system to prevent it, bullying by psychopaths could occur, but in a world of abundance individuals were free to leave the influence of such bullies at will. In pre-historic and indigenous societies, consensus methods then evolved to deal with disagreements and to manage psychopathic members of those tribes that settled in cohesive communities. As the world became more crowded, abundance gave way to scarcity and stable tribes and communities became increasingly transient. Anarchic decision-making became untenable as frontiers and resources became exhausted, and consensus methods became more difficult as numbers swelled and the sense of community disappeared. In some areas, decision-making became centralized in monarchies and oligarchies, essentially fascist systems. In others, less centralized, local warlords seized power and made the decisions. Both these new systems were unstable and often led to continuous wars and revolutions, but these usually produced nothing more than changes in the people in power — the contested anarchic or monarchic/oligarchic system remained. Countries like Afghanistan continue to waver between anarchy (decision-making by local warlords) and war. The laissez-faire “free market” is a form of contested anarchy, with the ‘tribes’ (corporations) of local warlords (CEOs) constantly fighting for dominance. As the cost of war rose, some nations decided to establish a new system for decision-making called ‘democracy’, in which the factions fighting for control would hold a staged war called an ‘election’, and then voters, responding mostly to propaganda, misinformation and bribery, would judge the ‘winners’ and install them in power for a fixed term. While less violent, the result of majority-rule democracy is the same as the result of war: the ‘winners’, and more particularly those who finance and wield influence over them, end up with all the decision-making power. In this system, the voters have no real stake in decision-making at all. In recent years, winner-take-all majority-rule democracy has been replaced, at least on a trial basis, with proportional representation democracy, where no group is declared the outright ‘winners’ and those selected to represent the voters must continuously negotiate with each other to achieve some sort of consensus on each issue. Critics of this system argue that this is too time-consuming and unstable, but in those nations with most experience in various forms of democracy, this method is growing in popularity (at least in peace-time). So there seems to be something in human nature longing for a return to the two decision-making systems that prevailed for most of our time on Earth: anarchy (which both right-libertarian “free market” adherants and anti-government neo-survivalists espouse), and consensus. I’m a theoretical anarchist. I like the idea of living without authority, and everyone making his/her own decisions. But I think, in this age of staggering overcrowding, inequality, complexity and scarcity, it’s hopelessly naive. We’ve seen, in cults and corporatist abuses from the wild West and the mafia to Jim Jones and Scientology to Enron and Madoff, the consequences of clinging to anarchic ideals. Perhaps after civilization collapses, when overcrowding and inequality and scarcity give way again to abundance, we can re-embrace such ideals. But for now, in my view, our only hope is consensus. So, let’s look at this very old (used by indigenous peoples for millennia) and very new method for decision-making. First, a definition from wikipedia: Consensus Decision-Making is a group decision-making process that not only seeks the agreement of most participants, but also the resolution or mitigation of minority objections and concerns.

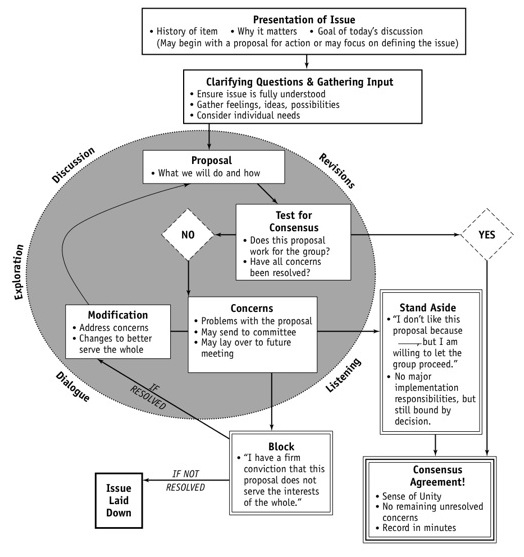

Consensus is not unanimity, but it is agreement among all members of a group that any concerns or objectives they may have are sufficiently small that they are willing to be bound by the decision. While it is not always an appropriate method for making decisions, it usually works: Consensus Decision-Making is an appropriate process whenever (a) there is an informed lack of agreement, and (b) there is a collective interest in achieving such agreement.

In other words, it won’t work if the group is insufficiently informed to have a rational position on the issue at hand, or to appreciate the essence of any disagreement they might have with others. If you’re ignorant of the essential facts, or don’t care about the issue, or aren’t or don’t feel bound by the decision, you can’t meaningfully agree to such a decision. And if you’ve been brainwashed or propagandized to misunderstand others’ position, and hence are unable to consider the issue objectively, consensus will likely be impossible. Likewise, if the decision choices are substantively aesthetic, matters of personal taste, consensus decision-making may be the wrong approach. And if the members of the group don’t trust or care about each other, attempts to achieve consensus may be fruitless. Consensus decision-making also won’t work if people are so inexperienced in using it that they don’t realize the consequences of their decisions. Or if they can (for any of a variety of reasons) be coerced, sweet-talked or ‘bought’ by others in the group. Or if there isn’t enough time (or the group is unwilling to allot enough time) for the process to take its course. Despite these drawbacks and limitations, this process is getting more and more attention these days. Businesses are increasingly forming as cooperatives and other forms of non-hierarchical ‘Natural Enterprise’, comprising equal partners who trust many decisions to the most skilled and informed partner, and make the remaining decisions by consensus. The ‘wisdom of crowds‘ uses the collective knowledge of a large group of informed and independent people to make better decisions than any expert or management group could make — while this isn’t a consensus process per se it does use the same ‘front end’ steps. Enterprises are realizing the value of improving collaboration with those within and outside the organization, and consensus decision-making can be an essential collaborative tool. And as the adversarial legal system collapses under it’s own weight, alternative disputes resolution processes that have much in common with the consensus decision-making process are getting increased use. As our political systems, prone to reducing everything to ‘either-or’ dichotomies that pit large power blocs against each other or allow the rich and powerful to make undemocratic back-room decisions, fall into disfavour, the consensus decision-making processes that are often used in jurisdictions using proportional representation to negotiate past impasses, are being more extensively studied and used. And as more people tire of dysfunctional centralized systems and establish community-based bottom-up networks and organizations to bring about change, they are finding that consensus decision-making is a very powerful and effective process for such groups. Here are my 10 reasons why consensus decision-making will be one of the most important capacities for people to develop and practice in this turbulent century. Think about what’s going on in the Middle East, or the disagreements that are hobbling your government, your business, or your community organization, and how consensus decision-making might be a better way, as you read this list:

If you’d like to learn more about the process, I’d recommend Tree’s Summary of Consensus Decision-Making, Consensus Queries, and Voting Fallbacks articles and Randy Schutt’s Examples of Cooperative Decision-Making Processes. After I attended the Bowen Island Art of Hosting event, I waxed rhapsodic about the facilitation process, and its importance. I feel much the same way about the consensus decision-making process. And the two are connected: Consensus decision-making requires all participants to become competent at and patient with the process, but also requires excellent facilitation — someone not directly affected by the direction or outcomes of the process who can work objectively and dispassionately to:

This is a huge task, and one that requires great skill, practice, intelligence, tact, alertness, grace, adaptability, and patience. Good facilitators are hard to find, and a poor facilitator can fatally damage the consensus decision-making process. Like facilitation, consensus decision-making is a capacity that can be learned, but one that must be practiced over a lifetime. We owe it to ourselves, our fellow humans and to future generations to get better at it, and start using it in every aspect of our lives. Nothing less than the future of our planet is at stake. Category: Collaboration

|

Thanks for referencing my work–i feel honored.I agree with a lot of what you wrote, and naturally i’m delighted that you are finding consensus such an important capacity. Among my points of divergence are:1. In the political section, it sounds like you are throwing a wide bunch of stuff into a category you call “anarchism,” much of which i would not personally put under that label. If one patriarchal figure is making the decisions or having overwhelming influence, then it’s not anarchy.2. Moving on from politics into something that i have some expertise in, i take some issue with your statement #3 that consensus “is non-confrontational and non-adversarial: Its objective is to look rationally at the issue, not to provoke emotional responses — anger, defensiveness, stubbornness. Cooler heads are encouraged and allowed to prevail.” This statement reinforces a common prejudice against emotions in meetings in North America. Personally, my goal as a facilitator is not to prevent emotional expression and confrontation; rather, it is to truly honor the wisdom in people’s feelings and use it as part of the guidance toward a high quality decision. And see, here i am being “adversarial” with you in this comment, but it’s part of a useful exchange (i hope). Yes, angry expression that is not worked with constructively can be damaging, but fear of confrontation can lead to groupthink, which is equally damaging. We need a balance, and more of the deep listening and other skills you mention.3. In response to your statement #8, i hate to admit it, but in the real world of meetings, articulate speakers in a consensus process may have more power than unskilled speakers. Just because a group chooses consensus as its decision method doesn’t make it immune to power differences. I think you’re right that in a well-functioning consensus group, other members use their discernment to filter what is being said, which provides a check on that power. And otherdecision methods besides consensus have even worse problems with power differences.4. In case it is useful, here is one more definition of consensus. This version comes from Larry Dressler: “Consensus is a cooperative process in which group members develop and agree to support a decision in the best interest of the whole.”Cheers.

I have reservations about the consensus form of decision making, not because I don’t support the principle – I do – but because of the requirement of agreement. The mechanism of agreement is designed to create a middle point, toward which fair-minded disputants will settle. However, there are issues where a middle point is elusive, and it is not clear that the middle point is always the best result.In addition, because the mechanism only works when there is agreement, there is considerable pressure toward agreement. This creates an environment where productive behaviour is defined as conformity and where dissension, no matter how well intended, is considered disruptive and even rude.For these reasons, I have long contemplated alternative forms of decision-making. And while the temptation is to compare consensus with previous individual and collective forms of decision-making, my own attention is directed toward a form of decision-making that is neither.Accordingly, I think that the table in the middle of the article should have another row. Because there is a sixth major way in which decisions get made.Under ‘Decisions’, instead of being either ‘individual’ or ‘collective’, it should be labeled ‘cooperative’. This is a system of decision-making where the ‘decisions’ are not explicitly articulated, but rather, are emergent from a network of connected but individual decision-makers. The ‘decision authority’ is uncontested.Under ‘power dynamics’ we should outline the basic elements of networks. In particular, the mechanisms defining network properties – nature of the connections, for example – should be detailed and evaluated against criteria of autonomy, diversity, openness and connectedness. And the effectiveness of individuals working within the network – ‘node power’, of you will, can be described by the density of their connections, the efficacy of their influence.Under ‘who ultimately decides’, the answer is, at once, ‘everybody’ and ‘nobody’.

An eloquent overview and good arguments for consensus, which I believe is a powerful tool. I feel energised to try this out in practice. Are there any “exercises” to, like, get a feel of this before you try it with live bullets so to speak?

There’s no more realism in promoting consensus than anarchy for the requirements for BOTH are simply not realised in this world.Consensus decision making needs:- informed people: you forgot how brainwashed and infoxicated people are from TV to movies, to advertisment and schools. Even worse most people lack the curiosity to get informed (though with Internet it’s never been so easy)- focused, deep listening and observing (body language) people: unfortunately younger generations are born with mobile phones, video games and dangerous chemicals in their bloods, which altogether decrease their attention span and wire their brain into a reflex prone machine.- time at hand for consensus to be built: our cultures are racing an economical war at each others, most people rush through their tight schedules and allow no time even to their own children and old parents, it’s a bit naive to expect them to take down to ‘decide’with other people.So basically while I’m aware it’s easier for concerned people like you (your readers and even me) to build consensus based business or communities, than anarchic ones. On a global scale I don’t see it happening before the civilisation collapse (because of above mentionned restrictions), and then after civilisation fall , in a world of abundance, in touch with nature, outside of culture, anarchy would be my favorite choice.

In the 90s the Dutch government runs on ‘consensus’ model. It was successful. The unions work with the government to solve labour problems, marketing strategies etc. The amazing thing is, the first time the labour union went on the streets again was with the present government (this goverment collapsed 3 times, this is their 4th go! and lead by the same PM. Go figure) where ‘consensus’ model no longer operates by the Dutch government. I think most of the discussions here (not just this post) are participated mostly by North Americans, where decision making is still is very much top-down. That makes it very interesting considers Open Source, AI etc. come from the US.

Good to see you are still blogging! I had thought you burned out and went away. Whew! :-)I wish people would at least mention sociocracy when talking of consensual decision making. But all in all, those of us who are meeting haters will not much thrive within this framework, which I think is way too… rooted in the rationalizing, “sitting on your butt ideating” model. Life is elsewhere. Neither tribes nor old fashioned communities make their decisions in meetings. People who live in communities talk to one another, work with one another, and that is how “issues” get discussed and chewed on… and they are worked through experientially. Traditions and customs are not created in meetings. Just my 2 cents.

One more thing. It would be more honest to write about the disadvantages of the consensus process. Eh?

I meant… *also* to write about the disadvantages. Oops.

I want to invite you to our Embassy by coming to our organization to be further be represented in the United Nations and interact their affiliated organizational departments such as UNICEF, UNEP, WHO, FAO, UNDP, and others. Administrators may select up to 5 (five) delegates to represent your group or agenda, one will serve as an Ambassador.Our group is dedicated to the promotion and use of the social media to unify nations and foster a global campaign initiated and is sponsored by initiatives of many world leaders to promote worldwide cooperation and change.An administrator or officer may contact me directly to get more details and send a delegation. The ambassador assignment involves a significant commitment and superior social networking ability, delegates will be qualified, trained, and certified as diplomats.Sincerely,Ambassador Col. David Jeffrey WrightSecretary-General MUNSNE Diplomatic Corps