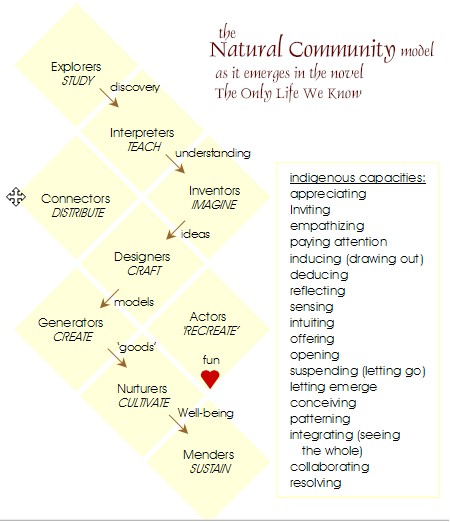

The following story, reproduced by permission, was written by Usul of the Blackfoot, about life after the collapse of our civilization. It is part of a longer exploration that describes our unsustainable civilization, why romantic neo-primitivism is no solution, and how he sees the collapse occurring. It was brought to my attention by Usul’s new webzine colleague, Magpie, who’s asking for submissions of models, history lessons, theories and stories of how we might live effectively in a post-civilization world. While I’m interested in comments on this story, I’d like to hear ideas on how it could be made better, rather than criticisms. Those who have read A Scientific Romance, or The World Without Us, or who have been following Jason Godesky’s (ex-Anthropik) Fifth World game (bottom image below is from the game site) will probably have some ideas here. My general thought, as someone who is writing a utopian novel, The Only Life We Know, set in a post-civilization world (see illustration above), and who has written a couple of stories as practice for that novel, is that while Usul’s portrait could well be accurate for some post-civilization villages, there will be astonishing diversity in such future communities, to the extent that it will take extraordinary (and probably collective) imagination to even conceive of what life after the crash will be like. So please join the conversation. How could this story be broadened, enhanced? What other stories, films, games and other media exist that portray a positive (utopian not dystopian) post-civilization future? How might we collaborate to create something better than any of us individually could come up with? [Author’s note: The use of a fictionalized post-civ society is meant only to show post-civilized solutions to the persistent problems of past societies. Although many of the things listed below would no doubt exist in a tangible post-civ community, this is by no means a strict formula for the creation of such a community. With that in mind:] by Usul of the Blackfoot Others are just beginning to stir. The village is coming to life. Many meet up in the communal food hall for a shared breakfast. Laughter and jovial conversation carry out of the food hall and down to the river, where several groups and individuals eat their food. Some others eat in their homes, preferring solitary quietude to the company of others so early in the day. When breakfast is finished people mill about, heading to a number of destinations. The bulk of the villagers make their way to various permaculture gardens. It is here that the village produces almost all the food it consumes. Work in the gardens is necessary but isn’t difficult. The damp nature of the area provides enough rainfall so that watering is mostly a non-issue for six to eight months of the year. And in the drier months, water that has been collected and stored is fed to the food crops by recycled metal pipes and newly fabricated ones made of bark. So, most of the work in the gardens is weeding, composting, mulching, and harvesting, which isn’t very much work at all. Early spring is a time for planting, a time for encouraging new life as the winter crops are dying out. People dig holes, fill them with compost, and transfer seeds and plant starts into the ground, singing songs all the while. A few others take soil samples. They’ll take the soil to a makeshift lab—probably in one of their homes—where its pH levels will be established. The pH paper they’ll use is made from dried cornhusks died purple with the juice of cabbages. This homemade litmus paper is but one example of high-tech/low-tech the community employs. Nearby, the folks working the garden utilize all manner of manual tools designed to put out maximum efficiency with minimal effort, maximum durability with minimal impact of the environment. Elsewhere in the village, a woman works one of the community’s primitive lathes. Though an advanced technology, skilled woodworkers make these by hand with tools they’ve also fashioned themselves. They’re then used by a number of people for a wide variety of applications: wood and metalworking, pottery, glassworking, and drilling among other things. In another area of the village, a group of people is conducting an experiment with spindles and hearthboards. Fire is an extremely important tool in post-civ life, as it always has been for humans. But the desire to live in harmony with the earth and to avoid tremendous resource consumption means that fires are once again made without electricity or lighters. This still leaves many “primitive” options in fire making, but the people of this community typically rely on hand drill and bow drill fires. So, a few of the most skilled fire makers and a handful of physicists have gathered together to determine the best spindle and hearthboard combinations. To be thorough, they’ve made spindles from a living and a dead sample of 20 species of native plants, and they’re using these to try and achieve a coal on each of 6 different hearthboards. Similar experiments have been done to determine the native woods best suited to bow making, and to find out which plants in the area yield the strongest and longest-lived fibers. The results of these studies are all printed on a very small scale using a manual press, plant inks, and paper either salvaged from the civilized world or made from pressed plant fibers. Once printed, these results are shared with neighboring communities. These communities reciprocate with their results in other fields. The results of this particular test are a long way off. As the participants alternate between spindles and hearthboards and record their findings, other people pursue a variety of tasks. Outside the village proper, the woods are teeming with human life where long ago saws and cranes and logging trucks decimated the ecosystem. Here instead, a crew of ecologists busy themselves with reforesting the area. This is an intimidating, generation-spanning goal, taken one step at a time. Today, most of the crew is concerned with the removal of invasive non-native plants, especially English ivy and Himalayan blackberries. A few others survey the area, looking for species of plant and animal life that indicate the health of the ecosystem. Not too far from the ecology crew, a small group of hunters track a deer that they’ve been after for hours. When the opportunity comes, they’ll kill the deer and take it back to the village to be skinned, butchered, and eaten. They’ve also recovered and killed three hares and a raccoon from their traps. Not everyone in the community agrees with the taking of animal life. In fact, there are many opinions in this post- civ village regarding people’s relationship with other animals. Some people, like the hunters, think that hunting and killing animals for all the resources their bodies provide is perfectly fine. They represent a minority in this specific village. Although they kill, they never do so excessively or for sport; these hunters possess formidable knowledge about ecology and understand their impact on a damaged but healing ecosystem. They only use bows, spears, and traps they’ve made themselves or salvaged from the old world. They never use tree stands or other lazy industrial abominations, for their prowess at stealth and tracking is extraordinary. And when they do kill they show reverence to the animal and to the forest, and they guarantee every part of the animal is used. A majority of people in the community disagree with the hunters. These people survive almost exclusively on crops grown in the village’s ubiquitous permaculture gardens and supplement their diets with food they scavenge in the wild. Though this majority is opposed to killing other animals, they don’t exclude animal food from their diets. This comes mainly in the form of eggs and goat’s milk cheese. Chickens are a crucial part of the vast permaculture gardens because they devour all kinds of pests and their waste acts as fertilizer. In similar fashion, the goats are useful to the forest rewilders and ecologists because they can survive exclusively on invasive plants. Besides goat cheese and eggs, these villagers occasionally consume animal flesh. The goats and chickens die eventually, and the villagers sometimes come across a fresh corpse in the woods. On such occasions these folks eat animal flesh and harvest animal bodies for bones, sinew, and hide. In our world these people would be called freegan. The rest of the villagers keep a traditional vegan diet. They make up a small minority, but everyone respects their opinions about veganism and their right to a vegan diet. These folks consume nothing but food grown in the permaculture gardens. Because of their increased reliance on the gardens, they typically put more time and effort into maintaining them. The peaceful coexistence and cooperation among all of these people, regardless of their dietary choices, is a result of the anarchist governance of the village. The village has meetings whenever they’re necessary, and its small population ensures that everyone truly has a voice and that every opinion matters. The consensus process—that is, reaching a decision everyone agrees upon—is on many occasions slow and tedious. However, the people of this community have plenty of time for talk and mediation since their “work day” consists of so few hours. Almost everyone in the village attends meetings, understanding that the freedom they enjoy is bound to the responsibilities of voluntary politics. The communal hall in which village meetings are conducted also doubles as a mediation hall. Mediation is the process by which personal disputes are settled and minor infractions of community “law” are remedied. Today, in the early afternoon, five people enter the hall to begin a mediation. They all sit together in a circle—no one superior to or more authoritative than anyone else—and begin. One of the people in the room has been accused of stealing by three of the others present. The fifth person is a trained mediator and empath. She has devoted most of her life to learning the ways in which various people interact, the ways people express emotion, the ways people reserve emotion, the meaning behind certain emotions, and how to help dissimilar people interact without violent or oppressive speech. She is neither judge nor jury, certainly not a cop, and the hall itself is nothing like a courtroom. Stealing is considered wrong and unnecessary in post-civ communities because all necessities are shared. The village has common tools, common food stores, common clothing for those who can’t make or scavenge their own, common medicinal herb stores, and housing for everyone. All people have access to these things at all times. Most people still keep personal property; not in the sense of land or resources, but belongings with emotional meaning and objects people make themselves. It is personal belongings the person is accused of stealing: a necklace made for one of the accusers by a friend, a bow of exceptional quality made by the owner, and a cedar vest made for the third accuser by his mother. If the thief had taken any of these items from the communal caches, no one would have noticed, let alone cared. But these were all taken from individuals and have personal meaning to each of them. Under the wise guidance of the mediator, the group comes to several conclusions. The accused admits to stealing these items, and explains that he has done so because he feels neglected by the others. They are all good friends and the thief felt ignored, unappreciated, and hurt, and didn’t know how to express his feelings. The three friends all pledge to be more mindful of his feelings and show him their love more often in the future. He apologizes, promises to return their things, and pledges to make amends for stealing from members of the community. In post-civ mediation there is no punishment as in the civilized world. More often than not, people care so deeply for their friends and community that they feel intense shame when they act unethically. When people are called out for mediation, every person involved states what they’d like to see happen as a result of the situation. In the case of the thief above, each side in the discussion has made promises to amend certain wrongs. In the interest of improving themselves and their community, the people involved will most likely keep these promises. Mediation doesn’t always work, because it relies on the willing participation of all parties involved in conflict. In this post-civ village, as in most, the penalty for continued oppressive behavior toward one’s friends or community or continued disinterest in solving problems with mediation results in exile. The need to invoke this penalty almost never arises, and when it is suggested as a solution to certain problems, the entire village meets and must reach consensus on the issue. Only one person has ever been exiled from this village, after showing over a period of many months he had no interest in community, anarchist politics, or post-civ ethics. However, the man accused of stealing is still interested in being a part of this community, like most people who act unethically. He has promised to make up for what he’s done. No one will hold him to this and no one dictates the terms of his recompense. Because he is handy at fixing broken things, he has decided to mend several things in disrepair owned by the friends he wronged. And to show the entire community he’s sorry for acting poorly, he’s decided to spend an extra half- day scavenging useful items from the past. This is a prudent choice, one he knows the larger community will appreciate. All post-civ communities, to some extent, make use of the almost inexhaustible supply of resources that can be harvested from the wasteful civilized world. All manner of discarded and forgotten tools and objects are recovered from the ruins of civilization. The benefits of scavenging and recycling the waste of the old world are twofold. It is first beneficial to the planet, as recycling and reusing old waste helps reduce the amount of trash polluting the world’s delicate ecosystems. It also allows post-civ communities and individuals to relearn sustainable, permacultural, non-industrialized ways of making all the tools and technologies they need and have forgotten. There are hundreds of examples of scavenged and recycled goods in this post-civ village alone. Upon the walls of the communal food hall are scores of cast-iron pans and steel pots, which will last indefinitely if properly cared for. In the event the village does need new dishes, the individuals who have learned metalworking, woodworking, glassworking, and pottery can easily make them with minimal impact on the earth. Throughout the village huge quantities of medicinal and edible plants are grown in old tires and raised beds made from disassembled shipping pallets. Ancient dumpsters are used to cultivate potatoes and sunchokes. As with the cast iron they’ll last almost indefinitely. By the time the tires and pallets eventually rot back into the earth, craftspeople will have made many replacement planters and raised beds. Glass jars are extremely useful, and are among the most abundant items scavenged from the old world. They are used for storing medicinal herbs, tinctures, harvested grains, seeds for planting, water, honey, beads, foodstuffs, etc. The village brewers seek out and use one-gallon glass jugs and five- to ten-gallon carboys for making booze. While they rely on these artifacts of the old world, they learn pottery or glassblowing in order to replace these vessels when there are no more to be found. Tins are equally useful and as highly sought after as glass jars. They’re used for making and storing char-cloth, storing percussive fire making supplies, storing needles and thread or sinew, and for storing and preserving many other things. In time these containers will erode and become useless, but will be easily replaced by those who can work bone, wood, stone, metal, bark, and even grass and reeds. On a larger scale, old vans and large trucks are used now as houses or as storage closets, or they’re converted into huge solar dehydrators. Many building materials from the civilized world are also scavenged and put toward new uses. Bricks, concrete chunks, wood, metal supports and beams, and even plastic are given new purpose in the post-civ world. As these things slowly decay and become scarcer, people in post-civ communities learn to fashion a plethora of shelters from natural materials: adobe hogans, long-term debris huts, tipis, wikkiups, and scavenged debris cabins. Besides scrounging old world materials for building and storage, people frequently put these materials to use in artistic creations. The importance of art in post-civ society can’t be overestimated. Interspersed throughout the village’s sprawling permaculture gardens are countless sculptures and murals, mostly made from recycled old world rubbish. Paintings, found object art, sculptures, and statues can be found in the communal food hall, the village meeting hall, and in most homes. On the east end of this village there is also a small amphitheater that acts as an open air historical gallery. In the civilized world art is thought of as the domain of the bourgeoisie and the wealthy, and is thought to be abstract and incomprehensible to most. In the post-civ world art belongs to and speaks to everyone. The giant metal sculptures and multitude of paintings and tapestries in the village play several important roles. Most of the art in the village portrays scenes of the past, visions of the civilized world and the world of industry, and they act as terrifying reminders of why a society made up of such things is odious and destructive. These images of the poor under the yoke of the rich, of the world being destroyed by industry and capitalist commerce, and visions of women being the slaves of men are used to teach children the errors of the past and to instill confidence in and satisfaction with the world post-civ society is building. This art also acts as tangible representations of post-civilized ethics and the merit of a society built on such values. Alongside the terrible portrayals of yesteryear, pieces of art in many forms show people of all genders, ages, and races working together, and they show humanity as a positive force in helping a damaged planet to heal. Art is also used as an instructional tool. Besides printing the results of studies, small presses are also used to publish educational material for those who learn best with visualizations and those who prefer to learn on their own. These materials almost always include illustrations or other forms of art. Art in post-civilized anarchist society is further used to exemplify the accumulated mythology of its people. In primitive societies, most people rely singly on superstition, intuition, and mythology or religion. In civilized societies, many people instead rely on logic, science, and mathematics, rejecting and belittling primitive ways of thinking about the world. Post-civilized society embraces all of these ways of thinking, and mythology is of particular importance. The myths of this village don’t just involve asking for things and showing thanks. Many people feel kinship to a certain animal. People talk of some animals as being wise, some mischievous. Some animals are thought to embody human traits, even to speak human languages. Many people look to certain animals for advice or blessings. Gods, goddesses, and genderless deities are invented and played with daily. Some talk about the god of lost-and-found and scavenged things, while others seek help from the patron deity of fletching. Many see the forest as a living goddess, or the moon as a lunatic trickster god. Belief in these myths and reliance upon them is by no means a religion, nor is it irrational. The people of this post-civ community still believe in reason and logic, and comprehend that myths aren’t the same as reality. They understand that myth or superstition ungoverned by reason causes crusades, evangelical genocide, and religious persecution. But they also recognize that fantastic imaginative thinking is a vital part of human experience, and that reason without myth causes emotional coldness, mental stagnation, and the limitation of human perception. In short, post-civ society recognizes the need for reason and science, magic and myth, and it fosters all of them. Beyond using physical art to express and embody myth, this village is fond of storytelling. Without television and other huge media keeping the populace pacified and numb, people need an outlet to the fantastic. Many evenings the people of this community gather together and weave tales for their mutual enjoyment. The village has four storytellers who have given themselves to the art and have mastered it. These four troubadours take turns each night telling all sorts of tales, epics, and odysseys. When they are finished, or on nights when none of them feel compelled to speak, their apprentices and other members of the village take the stage. The stories told span everything imaginable. All the old myths are told: Norse sagas, Greco-Roman myths, Aesop’s fables, tales of Japanese kami, parables from native peoples across North and South America, fables from across Africa, Celtic tales, even Christian and Islamic myths. Fantasy, science fiction, cyberpunk, and steampunk written in the civilized world are recounted in a similar fashion. And of course hundreds of new myths, myths that reflect the post-civilized world and its ethics, are told in kind. Not all the narrations of the master storytellers are myths. Many are tales of people who acted heroically in the face of oppression, some the tragic histories of people martyred in the struggle against fascism or the fight against slavery. Many of the new stories integrate reason and wisdom with myth, as in the tradition of Aesop. Animals are personified, given voices, and made to illustrate good and bad ethics, actions, and attitudes to children and adults alike. Most important of all, the stories told every night often give insight into the adventure and excitement of post-civilized life. Where once a world of inactivity and repression existed, there is now a world of community, coexistence, and thrilling newness. And when the story telling is over this night, the people of this post-civ village will go off to bed, off to stand night watch, off on a midnight trek through the woods, thinking all the while that tomorrow is another day of fulfillment and freedom. Category: Building a Community-Based Society

|

In this post-civ community a number of myths and rites are respected. Each time a fire is made, the maker thanks the spirits of the spindle and hearthboard, and the spirits of fire and oxygen. When plant starts or seeds are sewn into the ground, the planters ask the earth to harbor the new life being placed into it, and they talk to the plants themselves and encourage them to grow strong. When food plants are harvested, the harvesters thank the plants, the soil, the sky, and the earth itself. When weather is dry and the gardens need water, the earth and sky are beseeched to send rain.

In this post-civ community a number of myths and rites are respected. Each time a fire is made, the maker thanks the spirits of the spindle and hearthboard, and the spirits of fire and oxygen. When plant starts or seeds are sewn into the ground, the planters ask the earth to harbor the new life being placed into it, and they talk to the plants themselves and encourage them to grow strong. When food plants are harvested, the harvesters thank the plants, the soil, the sky, and the earth itself. When weather is dry and the gardens need water, the earth and sky are beseeched to send rain.

Ernest Callenbach’s novel Ecotopia portrays a positive post-civilization future. This book reminds me a lot of you, Dave.

This story is haunting. Post-civilization fiction isn’t a genre I’m familiar with at all, so I don’t have a lot to add…but this was wonderful to read. I’m sure I tend to romanticize alternative social setups, but I feel like I’m much more cut out for a society like this than the one in which I currently live…where can I sign up?

Well, I think it would help to be less didactic and PC. I thought freegan were dumpster divers.?I’d skip the spilling-out tits. After suffering the trussed up females of Star Trek, do we really need another installment? Women can be half naked and comfortable and believable and unobjectified, ya know… :-)I’d add greenhouses. More about vernacular building. Mmmm… will have to think about it. Where do the vegan get the vitamin B12? I don’t suppose Whole Foods made it. What’s been preoccupying me recently is… how do you live in a humid climate without the gadgets and without mildewing? — Nice try. Thanks for the link.