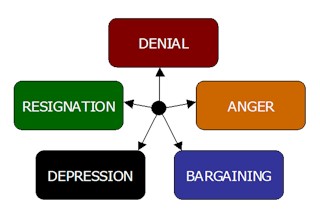

At a time of great distress and grief, the thought of having to speak to children about the loss of a loved one can bring on an unbearable additional anxiety. We no longer live in a world where children frequently witness death as a part of life, and so it is hard for them to grapple with, and hard on us to try to figure out how best to break such tragic news to them and help them through their own, unique stress and grief. They go through the same five stages that we do, in their own way. Furthermore, they may sense and ‘feed off’ our own unhappiness and anxiety. Here are ten things that we can do to make this difficult task a little easier: At a time of great distress and grief, the thought of having to speak to children about the loss of a loved one can bring on an unbearable additional anxiety. We no longer live in a world where children frequently witness death as a part of life, and so it is hard for them to grapple with, and hard on us to try to figure out how best to break such tragic news to them and help them through their own, unique stress and grief. They go through the same five stages that we do, in their own way. Furthermore, they may sense and ‘feed off’ our own unhappiness and anxiety. Here are ten things that we can do to make this difficult task a little easier:

Talk about it when you see it in everyday life Listen, be honest, patient, reassuring and calming In the stress to explain a tragic event to a child, there may be a temptation to do all the talking. It is important to listen carefully to what the child is saying, and not to anticipate or judge what he or she says. If his or her response seems casual or harsh, pay attention not only to the words but to the child’s body language and facial expression as well. We can’t expect children to be articulate about this subject, so it is important to give them time to express themselves, and to give ourselves time to understand what they are feeling behind the words they say. We must also be reassuring, and not lead the child to believe it is someone’s fault (especially not the child’s) — children often take stern or tearful discussions with adults to mean they, the child, must have done something wrong, so we must explicitly avoid or correct any such misimpression. And as hard as it may be in the face of our own anger and fear, it is important that we remain calm, even if the child’s initial reaction is, as it is commonly, one of anger or fear. Admit you don’t know all the answers Talk about different beliefs about what happens after we die Keep the message short and simple but be available It is usually better to state the facts calmly, simply and briefly, rather than going into detail and trying to anticipate and respond to the child’s questions and taxing his or her attention span. Then listen. The child will tell you if he or she needs more answers now. It is not uncommon for information like this, which the child usually has no frame of reference to digest, to take a while to sink in. This is not insensitivity. When he or she is ready with more thoughts or questions, that’s the time to continue the discussion, so it’s important to remain available and open to such conversations, even if they continue for an extended period of time. Talk in concrete terms about what will and won’t happen now — how the death will affect the child’s own life This, too, can be difficult to handle, since the questions and concerns of the child may seem very self-centred, even selfish. Appreciate that children know they are dependent on adults, and need to know whether that dependence will be changed or compromised by the loss of someone close. Try to see the situation from the child’s vulnerable point of view and reassure him or her, as much as possible, that little if anything will change in his or her life, and if there will be changes, what specifically will they be, when will they occur, and what are the important implications for the child. When they are powerless, children seek and need consistency, and in these situations we should try to give them that as much as we can. Avoid confusing metaphors about death As a coping mechanism, adults often resort to metaphors — being “called to Heaven”, “eternal sleep”, “going away”, “passed on to the other side” etc. They have a calming and sympathetic effect on us because we know they are metaphors. By contrast, a child will usually take such expressions literally and can become very confused or distraught by them. If the loved one was “taken by the angels” could the angels come for him or her too? If death is an “eternal sleep” should we be afraid to go to sleep in case we don’t awaken? If a senior relative died “of a protracted illness” should we be terrified of dying every time we get a cold? Children often don’t have enough grounding in the beliefs of a religion early in their lives to be able to handle a lot of perplexing explanations about the afterlife all of as sudden when a loved one dies. That doesn’t mean denying one’s religious convictions, but rather, unless the child has been taught these beliefs before and is comfortable with them, keeping the explanations short, simple and factual, avoiding the use of confusing and unfamiliar metaphors, and explaining other adults’ use of confusing metaphors as just “adults’ way of talking about things” — not to be taken literally. Be cautious of idealizing a deceased child in front of other children Be careful of suddenly becoming over-protective of children When a loved one is lost, there is a naturally tendency to become more protective of children in one’s care, but if carried to an extreme this can suffocate the child and cause fear, anxiety or resentment. This is something adults need to talk to each other about, to make sure they are not overreacting and causing undue additional stress to the child. Prepare children for visits to hospitals and funerals A funeral, or a visit to a hospital to see a dying person, can be very traumatic to children who aren’t prepared and don’t know what to expect. It’s important to tell them calmly and factually exactly what they are going to see and hear, including preparing them for the emotional outpouring of adults who are usually calm. It is more important that the child know what to expect than why, so there is, again, no need to answer questions that haven’t been asked. It’s also important that children have a choice about whether or not to attend these events. They should not feel coerced one way or the other. This decision of each child is a critical step in learning to take responsibility for one’s own decisions. This list was prepared with the guidance and inspiration of several articles written by experts in the subject, most notably an extensive presentation on this subject by Dr JW Worden reproduced at hospicenet.org. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

I would like to extend an invitation to you to join in on a collective blogging section of our upcoming winter issue of Reconstruction. The issue is the

When my second son was 5 years old he had a heart surgery.. affortunatedly everything resulted ok. The first night we spent together(after the surgery) he began asking me about his dead canary, the dog, the grandmother….. what was dying… what happened then… I felt that little person had touched death…. he was so calm, so clear in his doubts…. I told him I did not know… but that I was sure I was somewhere before I was born… that I could not remember how it was, but that I had a calm feeling about it…I asked him ¿do you remember where were you before you were born? he said no, how do you feel about it?… he said fine…. I told him that for sure we returned there….. He accepted this explanation in a very senseful way because it was something he could feel in himself.

The best policy is to tell the truth. Of course, to tell the truth you must know the truth.

I don’t have children, but if I did I’d most definitely make sure they had pets or get out and experience nature, because I think living with our animal friends helps kids learn a lot about responsibility, love, and compassion, as well as the cycles of life and death. I would also read Raymond Moody’s and Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s book, Life After Life, and Moody’s subsequent books on the subject, with my kids. I’d teach them how to deal with smaller losses using the same coping methods we’ve learned can be helpful during and after the loss of a loved one. I don’t think it’s good to scare kids by giving them too much too early, but better to ease them into the harder lessons. It’s possible that too many parents want to shield their kids entirely, and do until a big loss occurs, because they themselves don’t know how to handle grief. Grief is inevitable, so we all need help preparing for it.