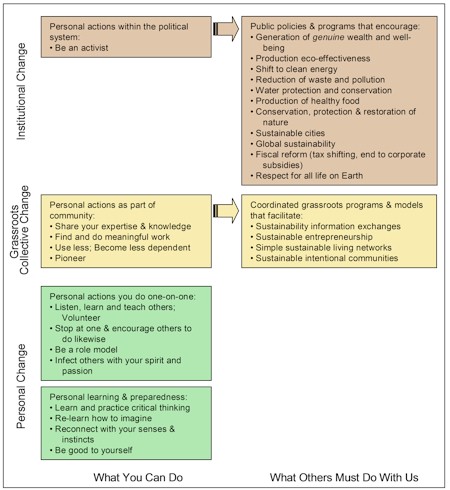

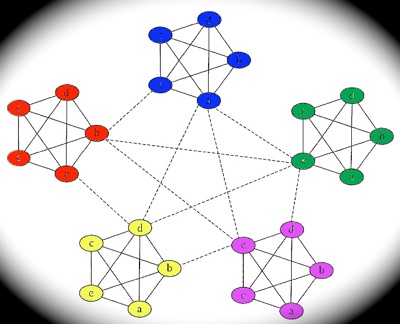

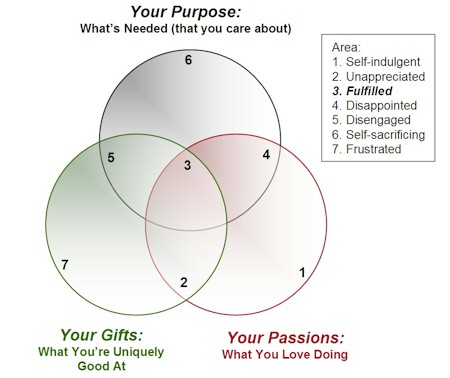

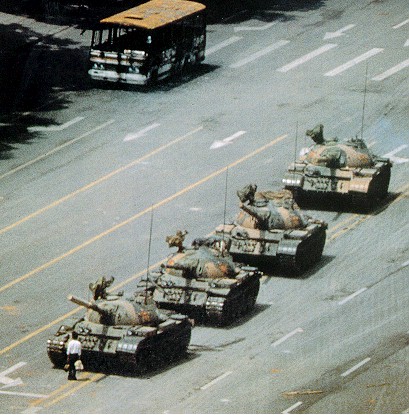

After the Bioneers conference last year, I wrote about the 24 steps to make political activism more effective. And, as the chart above shows, activism has long been part of my “what you can do to help save the world” list. Recently, however, I’ve become more skeptical in my writing about whether or not political activism really has any effect. Most of my attention has been focused on personal change, on adapting to the world rather than trying to make it better. More recently still, I’ve begun to think that personal change is equally futile: that we cannot be other than who we are, and that the best personal coping strategy is to know and accept yourself. My friend Janene has tempered my thoughts on this somewhat; she says that while we may not be able to change who we are, we can change what we do. To some extent this takes us full circle. If we have the opportunity and responsibility to change our behaviour, our activities, to make different choices about what we do, and don’t do, what is this if not political activism? And if those actions do make a difference, then skepticism about the effectiveness of political activism is at best unwarranted, and at worst defeatist. My political activist friends have called me on this, and I promised to recant any suggestion on these pages that political activism is a waste of time and energy. So I’m doing so. As Margaret Mead said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” She was right. Social and political movements have always pushed people and institutions to make important and meaningful change that they would not otherwise make, by appealing in part to their sense of what’s fair and just and reasonable (an intellectual appeal), but more importantly by appealing to human emotion, by moving them. Without such movements there would be no movement, and we would probably be living in a world with much more slavery, violence, destruction and tyranny than the one we live in now. I’ve been trying to figure out why this is so. I have a fairly optimistic view of human intention and behaviour, as befits an incurable idealist. But I also confess to being misanthropic — I don’t much like most people. I find them stupid, unimaginative, indifferent to the suffering of others, and conveniently ignorant and agnostic. It is easy to give up hope on people, and to blame “the system” that grinds the sense and sensibility out of them, and just give up. I believe, as John Gray has argued, that we humans, like most creatures, are preoccupied with the needs of the moment. We are myopic, both in time and space — unable to really care about what we cannot see and feel, or about what the future consequences of our actions might be. That’s not a criticism, just a Darwinian truth. That is who we are. The problem is one of scale. When something affects us, or our immediate circle, personally, it is in our nature to care about it, and, with some struggle (because in our modern world we do not get much practice building consensus, resolving conflicts, and really caring about those we haven’t personally selected to be part of our networks) to resolve it congenially, fairly and effectively. But the further away something gets from those intimate circles, the less capacity we have to understand it, to care about it, or to deal with it effectively. With distance and size it becomes remote, invisible, complex, unfathomable. We introduce hierarchy (whose effect is to increase efficiency and the concentration of power and reduce effectiveness, resilience, information-sharing and peer communication). We introduce agents, brokers, intermediaries, media and ‘representatives’ to whom we cede power and responsibility. As we become more distant and as the circle becomes much larger, we cannot care as much. Soon it takes a massive fear-based propaganda machine just to make us vote, or fight a foreign ‘enemy’ thousands of miles away. Likewise, when politicians are far removed from their constituents, they cease to know or care what those constituents individually want or feel, and focus instead on how to broadcast messages to get re-elected. If they’re business leaders, likewise removed by many layers and floors and oceans from the front line people, they cease to care about those people, and begin to think of them merely as ‘resources’ to be managed. There’s a new book out about government corruption in Kenya called It’s Our Turn to Eat. The title refers to the appeal of each elected government to its own tribal supporters that they have to seize power and gorge themselves quickly because after the next election some other tribe will be in power and they too will look after ‘their own’. The twist is that the elite in Kenya, across all tribal groups, exploits this tribal animosity and fear to distract the electorate from the fact that, whoever is in power, the elite still pull the strings, pay off the politicians, and hoard the resulting wealth. The objective is to subjugate and discourage the people, because that allows the elite to continue to rule unopposed. Then it all becomes a game of perpetuating power and wealth — stealing elections, ever-increasing disparity, police state laws, bribes, pork, subsidies and payoffs, propaganda, intimidation, media control, divide and conquer, and massive corruption. US 2000, Kenya or Iran 2009, it doesn’t matter. To think that this is a struggling-nation problem only is pure conceit. Thanks to distance, size, and scale, the benign inclinations of human nature are coopted, perverted and corrupted. Everything that works at a community level fails at the level of corporation and nation. We have shown, all over the world, again and again, that once we reach a certain size we become depraved, ungovernable. The role of the activist is to act as a counterbalance to this perversion, to speak truth to power, to bridge the distance, to hold those who are irresponsible and unaccountable, responsible and accountable. To intervene. To break down what is already broken. To enable what the people really want to be realized, despite everything. A step forward for every step back. A holding action. This is thankless work. So I want to say thank you. Without activists, the Republican neocons would still and forever control the US government. Without activists, the world would be full of gulags, torture prisons, brutalized, silent spouses and children. Without activists, the forests would all be gone, the air fouled, the oceans dead, the glaciers and ice-cap and permafrost melted into a brown sea. Without activists, women would have no vote and no right to choose, and people of colour would have no freedom. Without activists, the books with the most important ideas in human history would be banned, or never published. Without activists, the world’s children would be working in mines, and the world’s adults would be working in chains. Without activists, we would all be addicted to the poisons that Big Tobacco and Big Agribiz and Big Pharma and Big Energy try to convince us we cannot live without. Without activists, the only non-human animals would be farmed animals. Without activists, the world would be awash in billions of unwanted children. All of us must be activists, if we are to give this world a fighting chance. What should you do? Picking your cause is just like picking the work you’re meant to do, as I explain in my book Finding the Sweet Spot. This is not work for the half-hearted or easily-discouraged. So, just as in choosing the paying work that gives your life meaning, you need to identify and choose a cause that’s in your ‘sweet spot’ — something you love doing, and that you’re good at, and that is needed in the world, and that you care about. If you are no good at it you’ll get discouraged or burned out. If you don’t love the cause, you’ll end up disengaged. If it’s not really needed, if the world’s not ready for it, you’ll be unappreciated and frustrated. To find this, you must learn something about yourself, and then do some research about the world, about what’s really going on, about the points of intervention that will allow you to make a difference. There are a few ideas in the brown box in the top chart above, but it’s only a tiny segment of the work that needs to be done. Whether your cause is health or corruption or energy or pollution or water or food or conservation or animal welfare or urban despair or suburban sprawl or power or inequity, the process is the same: Find partners, a community of people who share your purpose and your cause and whose work and strengths complement your own, so that you get to do what you love and are good at and so that the sum of the team’s work is greater than its parts. Next, you need to be for something, not just against something. Always fighting against, as important as that work is, will drain your energy unless you also have a vision of a better way, something to replace what you’re battling. So you need to be not only an informed warrier but also an innovator, an entrepreneur, a visionary. And you need to be prepared to search insatiably and undogmatically for the truth, because ultimately that is your most powerful, and sometimes your only, weapon. Without it, your belief and passion are not enough. You also need to be able to articulate, simply, clearly and honestly, what you believe and why. There is power in intention and strength in numbers, but you will be unable to achieve either unless you are able to convey what is, and what needs to be done, to those who are ready to listen and to make common cause with you. You cannot do it alone, and you have to pace yourself. You need to understand too that many people will not be ready for your explanation, and that your response when you meet them is to be polite and to move on, not waste your energies trying to make them believe what they are not ready to believe. You must have faith that they will come around, in time, and you or one of those you have joined in common cause will be there, then, to welcome them. And at times you need to be ready to fight. You might think this would require courage, but if you believe in the cause, and you know it’s right, fighting for it will not be hard; in your mind there will be no choice. (What else, activists? What am I missing? Lessons from the trenches? Secrets of success?) We must all be activists, and relentless, and patient, and brilliant at it, because as long as the majority are hopeless, there is no hope. And because we cannot fail. We cannot. Until the day when it’s no one group’s turn to eat. Until there is enough for all, and more. Category: Activism: What You Can Do Now.

|

Another fine post, Dave. Your friend

Is being a political activist the same as being an active citizen? I think there is some confusion there… I learned from Nicanor Perlas that there is a difference between the political, the business and civil society. The purpose of the latter is to be clear on what values, what kind of culture we want. Then it is the work of politics and business to apply it to their areas of life. To see the difference was revealing to me!With love,Ria

I find your blog refreshing and delightful. I just added a short quote from this entry, and the link, to the section entitled “Winning The Battle for Hearts and Minds” [ http://z7.invisionfree.com/E_Pluribus_Unum/index.php?showforum=165 ].

Very nice post Dave. I loved it. Only thing is the it is not easy to swim against the society, but as you said if we really care, there is no other option. Thanks for the inspiring and enlightening post as all the others too

Isn’t this the usual oppressed vs. oppressor outlook? Maybe you can make a difference just by being a controversial part of the system.I could never be an activist. All of the ones I’ve seen are shamefully one-sided and simply ignore contrary evidence and have no use for moderation. They are just like the things that they hate in spirit but simply have a difference of opinion.

I’m glad to see you come around on this, and to have articulated how and why so eloquently.One thing I find interesting is that I myself am coming into my own voice as an activist. I’m still semi-reluctant to call myself that – I must prefer being an advocate or a facilitator – and the reasons for that are exactly as mattbg describes: I don’t want to be thought of as blindly believing one thing or another, wanting the benefit of some at the expense of others. I’ve perceived some strange sense of animosity from others who feel I should be more radical, or am uneducated as a result of not falling in line with their tactics. (I’m grateful that I can now call those same people allies.)My chosen area is urban and transportation planning, but just because I advocate for fewer cars doesn’t mean I want economic adversity for people living in suburbs: all I see is a system that’s restricted their choices and skewed their sense of what’s valuable in their lives, and the potential to expose them to the different outcomes associated with other choices.I’ve also been reading about shadow work: the integration of what we like and want for ourselves, with the things we push away. That’s why I perceive anger to be a motivator of lower quality than deeper acceptance of both the sources of injustice and the role of individuals in working for or supporting the change, even if they aren’t always in the position to live it.Further to mattbg’s, I would say that most people, especially my age and slightly older, agree with him – and that’s why they do their activist work through things like social enterprises and organizations that get shit done, rather than pleading tirelessly with politicians trying to convince them with facts and figures. It’s quite a bit harder to argue with outcomes, models that are proven, and recipes for replication (though some certainly still try). It’s the reason my most recent work focuses not only on making governments more open and responsive, but also on empowering citizens to collaborate and organize to bypass government altogether. The advantages that gave governments their former value looks to be diminishing, and I think it will certainly need to cast in a new light, as our collective cooperative capabilities have been enhanced and as we learn to wield it for good or ill.