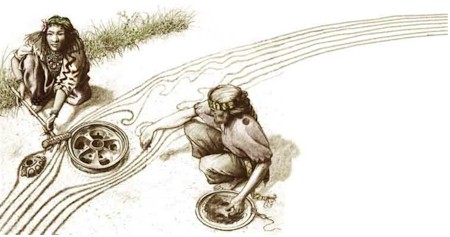

image from the 1992 documentary film “Baraka” For over five years I have been working on a novel tentatively called The Only Life We Know. The novel is set in the year 2200, a century or more after the crash of our civilization. It presumes that in 2009 we are at or near “peak everything”, and that all of the activities that have accelerated up an every-increasing curve since 1800 (or in some cases before) — consumption of land and natural resources, human population, pollution emissions, and production of more and more stuff, most of which ends up in landfills or worse — will soon follow a similar sharp drop down the other side of the normal curve, such that in 2200 we will be back to pre-industrial levels, 90% below today’s. So in my setting in 2200 there are only 500 million people left on the planet, a population that continues to drop gradually. The economy is subsistence and local, since there is no cheap oil to enable significant long-range transportation of goods or people. But it is the opposite of the popular, violent “Mad Max” scenario of post-civilization collapse. A study of history indicates that, unlike inter-civilizational wars, post-civilizational collapses are generally quite peaceful, although they do entail in their early-collapse stages a lot of death (mostly from starvation and disease), suffering and turmoil. Most civilizational collapses (read Jared Diamond or Ronald Wright) have been mass exoduses, as people flee fragile, unsustainable centralized locations in search of land, food and water to make a new, community-based beginning. They are, on a mass scale, a “walking away” from complicated systems that simply no longer work. My novel presumes that, as a decreasing number of humans fan out into the countryside, they find much of it degraded, but (especially in more Northern areas) they discover plentiful unused land suitable for small collaborative settlements, with solar power and permaculture providing a new sustainable way of life (I am hoping these recently-rediscovered technologies will not be lost along with our civilization’s soon-to-be useless oil-dependent technologies). And, as the buffers between communities get larger (with diminishing population) and transportation and other social interaction between communities become rarer, I sense that what will happen by 2200 is what we discover in most isolated gatherer-hunter societies: A staggering degree of cultural diversity, with a de-homogenization of language, adornment and behaviour, to the point that adjacent communities may be so different as to be nearly unrecognizable to each other. The principal driver for this will be de-urbanization, a hollowing out and abandonment of cities (also very common in civilizational collapses), since cities are inherently dependent on outside resources and hence are inherently unsustainable. We won’t go back to the Wild West or slavery or feudalism, though; instead we’ll go forward to a world that combines ancient indigenous wisdom with today’s and tomorrow’s (to the extent they can be tweaked to be sustainable) innovations — gliders, hot-air balloons, grafting of plants, straw-bale construction, human- and solar-powered looms, cameras, recordings, and other creative, artistic and scientific devices. The original plan was to bring this out in a series of short stories within the novel, each about one such culture, narrated by a young nomad travelling between them, and interspersed with a gradually-revealed story about the civilizational collapse that preceded this new beginning. I envision a proliferation of new local languages by 2200, completely different forms of art, wildly divergent spiritual beliefs etc., in each community, and I had intended to present these in the novel through conversations between the travelling nomad and the citizens of each community, and her observations and reflections about these communities. But I recently started thinking about another way to do this, that would get around the challenges of trying to depict such completely alien cultures and languages using written text in our very limited and culturally constrained 21st century languages. What if, instead of presenting this future in a novel, I presented it in a film? And what if, instead of writing a screenplay with dialogue that has the same problems of language as a novel, the screenplay had no words? What if, in other words, it were presented as a kind of two-centuries-later update of the cultural documentary Baraka (a Sufi word meaning “the weaving of life together”)? For those not familiar with this film, or with the films that inspired it — Koyaanisqatsi (Life Out of Balance) and Powaqqatsi (Life in Transformation) — Baraka is a set of twenty sequential visual vignettes, of about five minutes duration each, set in places around the world, depicting different aspects of the human condition. It has no plot, no actors, no script (in the conventional sense) and no dialogue. The picture above from this film is of a girl from the Kayapo tribe in the Brasilian rainforest. It could easily, I think, also be in my film set in the year 2200. I have been working with a cinematographer friend, Danielle Seville, to scope out how we could make this film. What I envision is starting with a set of premises about life in 2200 — mainly, that it would be peaceful, joyful, sustainable, and diverse, a world where (like humans did before the invention of tools and technologies) we scavenge much of what we need — except that in 2200, we will scavenge largely from the abandoned relics of the “civilized” world. It will be a world of sufficiency but also one of great comfort and spiritual rediscovery, as we will have re-learned how to live in the natural world, in concert and in balance with the rest of life on Earth. To try to imagine such a diverse future world is, I think, beyond the capacity of any one person (I’ve certainly tried, as hundreds of pages of discarded text from my novel attest). So instead, what I intend to do is to bring together a group of very imaginative people in a Creation Event and have us work collaboratively to develop the imagery, future cultures, music and sound the film would capture. I envision having artists and anthropologists and students of indigenous cultures past and present among the collaborators. I can see us sketching out and improvisationally acting out the scenes in real time, wordlessly, in Open Space. We’d have make-up artists and henna artists and tattoo artists and body-painters and animators and photoshoppers developing models of what we would look like and how we’d behave, using the participants as their canvasses. The Creation Event would itself be filmed. And then it would be my job, working with Danielle and her team, to craft a screenplay with “scenes from the future” that captures all of these ideas, and then to assemble a team of improvisors (not actors, really) to wordlessly act out these brief scenes. Part of the challenge will be to capture the reconnection of the human species with all-life-on-Earth, with scenes (like the image above from Baraka) that position us in the context of a rediscovered natural world, one that envelopes and welcomes and towers over us (rather than one we try to control), and offers us food, shelter, water, meaning, love — everything we ever needed. Much of the film, then, will not portray humans at all, but rather the natural places where we will then live, and the creatures we will share those places with, in sacred balance. That’s the idea so far, anyway. Category: Creative Works

|