Last evening I spent a couple of hours with three of my Bowen In Transition colleagues — Don Marshall, Rob Cairns and Robert Ballantyne — discussing what, if anything, we might do to start preparing our community (Bowen Island, off Vancouver BC, population 3800, area 20 sq. mi.) for the economic, energy and ecological crises — and perhaps even collapse — we expect to see in the coming decades.

Last evening I spent a couple of hours with three of my Bowen In Transition colleagues — Don Marshall, Rob Cairns and Robert Ballantyne — discussing what, if anything, we might do to start preparing our community (Bowen Island, off Vancouver BC, population 3800, area 20 sq. mi.) for the economic, energy and ecological crises — and perhaps even collapse — we expect to see in the coming decades.

Bowen in Transition, like many global Transition Initiative communities, is already doing several short-term small-step activities — learning about and (at a personal level) applying permaculture principles, obtaining and acting upon home energy audits, compiling a list of local experts in sustainable food, energy, building etc., holding awareness events etc. But as I noted in my recent Preparing for the Unimaginable post, I am concerned that we need to start thinking about longer-term, larger-scale, community-wide changes if we want to have a community sufficiently competent, self-sufficient and resilient enough to sustain ourselves through major and enduring crises.

I have read some of the “energy descent plans” of some of the leading Transition communities, and they strike me as being long on ideals and objectives and short on credible strategy — how to get there from here. And while my original thought was to draft a “Transition and Resilience Plan” that would include current-state data, scenarios, impact analyses and detailed action plans by community segment (food, energy etc.), I have come to realize that our future is so “unimaginable” that strategic planning is impossible — we cannot begin to know what we must plan for, and if we guess, we will be almost certainly so wrong that our plan will prove mostly useless.

Instead, I wondered if it made sense to have what Don, Rob and Robert called a “Working Towards” plan — specific ideas for helping us (1) build community and increase collaboration and sharing, (2) reduce dependence on imports and centralized systems and increase self-sufficiency, and (3) prepare psychologically and increase resilience for whatever the future holds. The idea was to start doing this within our 40-person Bowen in Transition group, and then engage others, until a majority of Bowen Islanders have acquired this knowledge and these capacities, and Bowen has become a real community. “Working Towards” these three objectives — community, self-sufficiency and psychological resilience — seemed to be something we could all agree on regardless of our ideology.

The more I thought about this ambitious goal, the more skeptical I became. Even if we could get our 40 Transition-savvy members to collectively model this behaviour (when we can’t get most of them to even show up for meetings), how could we possibly scale this up to a couple of thousand people?

As we talked, it was clear that each of us was sufficiently passionate about Transition to stay involved in it to some extent, focused mostly on short-term payback actions in the areas each of us cares about — for Don that includes water, waste management and well-being, for Rob it includes renewable energy, conservation and sustainable technology, for Robert it includes learning and education, and for me it includes livelihoods, transportation, ecological sustainability and self-governance. But as Rob pointed out, most Bowen Islanders are so busy (and stressed) looking after (and out for) family, homes and careers they have no cycles left to do more than vote, sign petitions, and attend occasional information meetings. Transition, even for the aware, is mostly in the “important but not urgent” category.

How do we make Transition urgent, or, if not urgent, at least easy or fun to be involved in in some meaningful way? Robert talked about the value of stories in getting people to a common understanding, which might be a way to create a sense of urgency. He said most Bowen Islanders came here from elsewhere, and their story is mostly about why they came here and what they consciously gave up to do so.

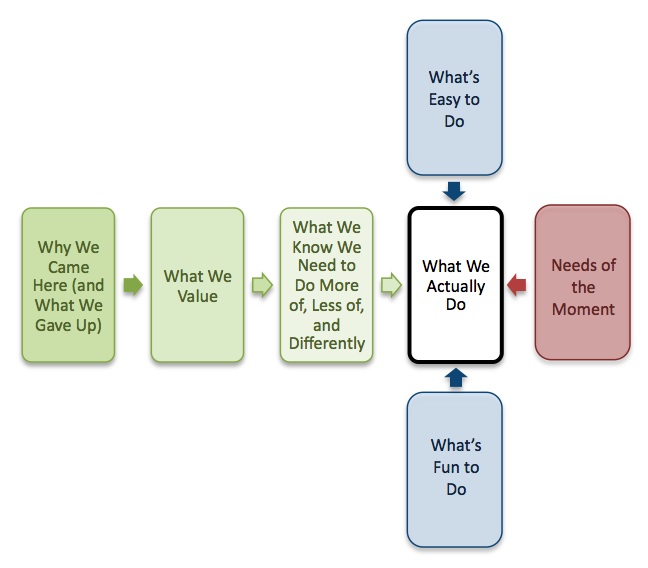

Our story, he explained, reflects and drives our values, and those in turn determine what we think is important to do in the world. Combine that with Pollard’s Law (we do what we must — looking after personal imperatives and addressing the needs of the moment; then we do what’s easy; and then we do what’s fun — what we love doing) and you get something like the graphic above. It explains (left side) why 40 Bowen Islanders gave up a day of their time without much convincing to take our crash course in Transition; it also explains why it’s so difficult to get them/us to do much more.

I talked a bit about Resilience Circles — the new movement that Tree told me about and that Transition US is working with. A resilience circle is:

A small group of 10 – 20 people that comes together to increase personal security during these challenging times. Circles have three purposes: learning, mutual aid, and social action. The economy is going through a deep transition, and economic security is eroding for millions of people. We’re worried about our financial security and about the future we are creating for our children. Many of us aren’t part of communities where we can talk openly about these challenges and fears.

Tree’s group in South Eugene, Oregon, that I mentioned in my post on Building Local Social Capital, exemplifies resilience circles (although it does not call itself that and did not follow the Resilience Circle process). Could such circles be the model that might allow us to bootstrap community to a community-wide scale? One presenter to Transition US suggested that a converging of the Transition and Resilience Circle “methodologies” might allow us to do just that.

The challenge with doing this is that I don’t think you can just go about setting up resilience circles in a coherent and organized way. These are substantially self-organized groups. And unlike Transition groups (which tend to have local champions that coordinate and hold them together), resilience circles appear to be more collectively-managed, with no one particularly in charge or depended upon for their continuance.

The four of us discussed the “magic” of such small “sticky” groups that keep going without a leader or end objective. We each had some experience of such groups — mine was (is) a group that meets monthly for breakfast in Toronto, that I co-founded and which is still going strong without me more than a decade later. It has no leader, and sending out reminders is unprompted and self-organized. It has often had guests, who occasionally join the group, and has had a few larger-group and longer events, but it has generally had about eight members at any one time, of whom usually 5-7 show up each month. Is there something magic about this number, we wondered, as Christopher Allen has suggested (his research suggests ideal size of a working group is 5-7 people and ideal size of a “community” is about 50 people)?

If he’s right, then perhaps instead of trying to create and sustain an Island-wide Transition group we should be looking to create Resilience Circles in each immediate neighbourhood in which one or more of our 40 Bowen in Transition members lives. What would happen if each of us were to call up, out of the blue, our immediate neighbours (whether we know them or not), invite them to a “block party”, and gauge whether there is sufficient interest among them to self-organize a Resilience Circle? This kind of “cellular organization” has worked well for others.

Then, instead of the primary role of Bowen in Transition being Island-wide awareness-building and member recruitment as it is now, it might evolve into a much simpler role of visiting on a rotating basis the 20 or 30 Resilience Circles on the Island, during their get-togethers, suggesting Transition-related activities to them and sharing “success” stories between/among the different circles. If we could link and network, say, 25 Resilience Circles of a dozen people each, that would be 300 people in the Bowen in Transition network, instead of 40.

The question is whether such a network of circles could evolve into a true model “community”. That raises the question What exactly is a “community” anyway? If we mean it in the sense that we need to “build local community” to be able to take on additional responsibilities when local crises hit and central authorities are no longer able to respond, and to be able to collaborate and share and make decisions in our collective interest, and support each other, then I would say a community is a group of people (around 50 if Christopher is right) who collectively have these attributes:

- They know and care about each other, and help each other actively and voluntarily rather than out of a sense of obligation or contract.

- They collectively have the capacities to make a life together in a relatively independent, self-sufficient and self-managed way, and to support each other.

- They care about the same things. That may be shared values, or shared longer-term objectives, or may be just the result of being thrown together to cope with one or more shared crises.

- They live in a geographically contiguous area and have a shared sense of place and connection to the land. (I know this proviso will be controversial among “virtual community” fans, and I am not saying that virtual groups can’t do some of these things well, but they can’t do all of them, especially if the crises at hand take from us much of today’s taken-for-granted technology, which I think they will.)

So today 50 people in an area of 500 people could constitute a community, if it was not too far-flung. And then if and when we find ourselves in a world of multiple crises or total social collapse, these 500 people could re-form into ten communities of 50 people each, with 5 people in each of the new communities having already learned how to live in community, and hence able to show and teach the other 45. They would make natural community “federations” of 500 people, and these federations might, as with indigenous confederations, be granted responsibility and resources from the individual communities for doing certain things that are impractical for a group of only 50 to do.

How many circles, then, does it take to make a community? If a circle is 5-7, it would take 7-10. If a circle is 15 (as in the Resilient Circles model) it would only take 3-4. We can’t prescribe it — it needs to evolve to suit the needs and culture of the people and place, and will probably vary.

But I’m intrigued about the possibility of creating a viable, self-sustaining and intimate Resilience Community from neighbourhood cells up instead of from municipality down. And I’m intrigued about the idea of “Working Toward” Transition not by compiling a plan, but organically by developing commitment, compassion, capacities and a sense of urgency in small federated groups, and allowing their collective wisdom to percolate across, until, in our collective wisdom, we are ready for whatever we, and coming generations, must face in the years and decades ahead.

top drawing by Nancy Margulies

Pingback: How Many Circles Does it Take to Make a Community? « UKIAH BLOG

Pingback: How Many Circles Does it Take to Make a Community? | Transition Ukiah Valley

hi Dave, have you heard about Gaviotas, the legendary village in Colombia created by a group of visionaries lead by Paolo Lugari about 40 years ago? Alan Weisman wrote a book about it in the 1990’s.

I recently read that a couple of guys from New Mexico wanted to create an educational centre involving teenagers for learning organic agriculture, renewable energy and more. They found Weisman’s book and thought that Gaviotas was exactly what they wanted to create; a few years later they managed to visit Gaviotas (this was in 2004-2005 i think). They went, had the opportunity to meet Lugari himself, were amazed of all the things they found, about the ways they work, the things they have accomplished, like the 20,000 acres of forest they have created, about how much they keep changing from their original ideas, and much more.

One of the most important messages is what they say Lugari told them that he never intended for Gaviotas to serve as a blueprint for sustainable development, or even a clearinghouse of appropriate technologies. Instead, he wanted to show the world that is was possible to live sustainable by drawing on local resources, or as he describes is, “living within the economy of the near.”

And Lugari has done so by staying faithful to two principles: allowing space for adaptation and creativity, and ensuring that everyone, not just “experts”, is involved and empowered.

One of Lugari’s mantras for their work is A.V.V., “alli vamos viendo”, meaning “we will see what happens as we go along.”

Those guys found that “it became clear to us that most of the successes at Gaviotas were not a result of brilliant planning but of a trial and error process, replete with wrong turns and detours. “Gaviotas showed us that there is not an orchestrated march towards a finished product –there is only the process, the unpredictable evolution of strategies and ideas.”

And this my friend, is what i understand by “BEING RESILIENT”…

Too much talking, too much planning… time for Action is long overdue ! !

Methinks that “…40 Bowen Islanders (giving)up a day of their time without much convincing to take our crash course in Transition…” lies at the heart of the problem. The modern hyper-educated/hyper-stimulated mind has been programmed to believe that if you take a course or read a book you’ve done the work; done all that’s necessary – until the next ‘crash course’ in something-or-other comes along. In between times the modern h-e/h-s mind segues back to what it believes to be of imminent importance, as you pointed out.

I know of no way around this other than – perhaps – the advent of the ‘event’ itself to bring about community. If/when that happens, those of you who seem to be most concerned and deeply involved will automatically become leaders into community. Meanwhile all you can hope to do is teach – you cannot force community to happen.

Intrigued by this question. Thanks for exploring it.

Love how you post “My Gravitational Community.”

I would respectfully offer that your definition of community is fatally flawed from the very outset. Having lived in a mostly self-contained community (a rural farming village in the Balkans) for a while, I think your description of a community where people help voluntarily and not out of a sense of obligation is at the heart of why so few so-called “communities” these days manage to actually function as such. The fat of the matter is that if we do not feel obliged to help and work with others in our community, whether that obligation is based on religion, family ties, or some other form of tradition, we will not develop a true bond with these people. The biggest problem with “creating” community in this failing industrial era is that we don’t really need these other people (except, perhaps on an intellectual/ideological level), and we can exist without them, and even worse, if we decide we don’t like the community we have, we can easily find another or at least insulate ourselves by only associating with people we happen to connect with. This arises, I think, in part from the Liberal -in the philosophical sense- idea that we belong to ourselves, and that our freedom and personhood is tied to our individuality. If we are not willing to submit ourselves to being obliged to others, even and especially when it is difficult and restrictive to our own freedom, we will perpetually fail to build durable communities. Wendell Berry, when speaking of community often uses the term “membership”, which is uses the old Christian analogy of the Church as a human body, where each member is a part of the whole, but not all the same, and not interchangeable. Furthermore in this conception of membership, and one of the critical aspects that seem missing in most discussions of community is that the various members cannot exist without the others, as the “body” only functions as a whole.

Norberto, bravo! And Martin, I agree completely. My concern is that when the s**t hits the fan, people will panic and fall into reactionary “survival” mode rather than seeing Transition change champions as leaders and visionaries.

Rade, we’re not so far apart. My late friend Joe Bageant said “community is born of necessity” and having visited many intentional communities I agree that it’s often easier to resolve conflict by forcing someone out than through community-building measures like consensus. That’s why I think co-housing (where you have all your money tied up in your investment in your house in a community) is both more collaborative and more sustainable — it’s much harder to quit when the going gets tough. I do think there are communities and circles that meet my 4 criteria for true community — their members have selected each other deliberately because they do care about them and share values and/or objectives. But they are merely experiments. I just want to believe that we can get enough autonomous experiments going in one area, and link them together into a (quasi-)community, so that they will be the foundation on which real functional community can be created when we have no other choice. We’ll have enough other things to worry about then without having to learn how to live together in a fundamentally different way. It may not work, but it’s the best I’ve come up with so far.

Well I certainly didn’t want to imply that we were diametrically opposed, I just don’t see how the late Mr. Bageant’s (may he rest in peace, he was one of a kind!) comment applies to most intentional communities, at least one’s I’ve seen, precisely because they are born of choice, not necessity. There may not be a better solution, but I think it is important to be honest with ourselves and understand that “helping my commune-mate because we are both Progressives committed to permaculture.” is not the same quality of relationship as “I am helping my neighbor because his father saved my father’s life in the War and I am Godfather to his children.”

Again perhaps there is not a solution to the mess we modern industrial men and women have made of our communities, I just want to offer that perhaps we need to approach community building with a greater sense of humility and, dare I say, repentence. It is curious to me that people who are dedicated to the idea of permaculture for their gardens, end up throwing the principle of imitating nature out the window when it comes to social and community organization (or see nothing wrong with trying to transplant a social structure and ethos to a time and place far-removed from where it developed).

Dave; I believe your assumption and concern “… that when the s**t hits the fan, people will panic and fall into reactionary ‘survival’ mode…” is correct, but only partly so. There will be those – very likely a minority at first – who will see “…Transition change champions as leaders and visionaries.” These folks will likely immediately form into a larger core that, with enough fortitude and luck, will expand to form the community(ies) you envision.

Also, I was struck by the logic of your remark concerning co-housing; it may be the only viable way to bring about community in these times since it involves money as representative of commitment to an idea – and that type of commitment is the one most broadly understood in these times, now that a particular philosophical outlook or worldview no longer seems to cut it.

Martin, cohousing is out of reach for most people nowadays. Fuggedaboudit unless you are well padded.

Dave, it sounds like the 4 of youz are it. Go and do something, something interesting. See whom it draws to you.

Hi Dave,

Thanks for your insight and inspiration. It confirms an approach I’m taking to (finally) start up some kind of transition group/circle in my neighborhood. Thought I’d share an epiphany I had on this recently. After sending out the invite to a first neighborhood gathering, I attended a Gartner conference and heard Seth Godin (author & blogger) speak to 3k attendees – advising them on how to market & build communities around their brand in the new social/customer-powered media world. He said ..don’t live ‘in the box’ – there are too many rules, constraints — and don’t live ‘outside the box’ – where there’s no support structures or models. He said – you want to live on the ‘edges’ of the box. …Edges, I though…that’s a permaculture priniciple .. edges in nature is where most the life is … where water meets land, forest meets valley. Permaculture design says to ‘maximize edges’ for more life in your landscape. It was then, that I realized why I wanted to start in my neighborhood – because it is my life’s edges. Our homes are our boxes (everyone closes the garage door right upon getting home) and our edges are the front yards ( backyards are fenced). It’s not that easy – cuz I live in a very right-winged (climate-change denying) suburban neighborhood – but I have about 3 neighbors (and 5+other friends) coming – so we’ll just see how it goes.

Hi Dave,

This is an idea whose time has come. Here in the Commercial Drive neighbourhood, in Vancouver, Cabot Lyford is kicking off an experiment in what he is calling “Right Livelihood Circles” (inspired in large part by Resilience Circles) starting April 11th. You can ready an article he’s written about it in the latest edition of the Village Vancouver Newsletter here: http://villagevancouvernews.blogspot.ca/p/right-livelihood-circles-finding-your.html. I will send him a link to your article as well, as I think that there are a lot of great insights here that are very applicable to what Cabot is spearheading!

Thanks,

Jordan

Pingback: The answer is the circle. The question is going to get thrown at you any time soon. | A Very Beautiful Place

Dave,

Jordan Bober from Village Vancouver introduced me to your amazing blog. I am starting a Right Livelihood Circle here in Vancouver East, and I hope I can tap into your considerable expertise to help move things along. We may even be able to get a bit of national currency to sweeten the deal, especially if we act soon. Please contact me, and anyone in Vancouver is welcome to visit http://www.villagevancouver.ca/group/right-livelihood-circles and join the party.

Hi Dave,

You are on your way toward something important here. Communities of fifty sound about right for greatest integrity and flexibility…. so how does that relate to the 3800 inhabitants of the island currently? Overlapping circles would seem to be the right answer.

I believe that if your transition group can help to implement a couple of different types of circles you could be well on your way to what you are looking for. First…. geographically based social groups: block parties, pot luck dinners, barn dances and so forth. Encourage social bonding within neighborhoods. Second…. interest groups: permaculture/garden clubs, fishing clubs, “barn raising” with cob or other sustainable techniques — whatever interests may be prevalent amongst the residents. (This one might take longer simply to identify the interests that can be shared). If you can successful inspire at least some of these groups to flourish, you will have the beginnings of the key for future transition: bonds of friendship and love.

Now…. before anybody flips out on that… I’m not talking about the hippie conception of love…. at least not as portrayed by hollywood. But I am absolutely certain that time, working together, and common interests will almost invariable create a love relationship which combined with inter-dependance creates an environment where obligation is a joy rather than a chore. Or at very least makes it acceptable rather than odious. And that is the point where true community begins to occur…..

Imagine, a few years down the road…. put on a community faire organized by all of the varying groups to showcase what they are doing and what they are about. Block party rolled into exhibition with friendly contests, and lots of food. Sounds like fun ;-)

Janene

Thanks for the comments and conversation everyone. There are drawbacks to all existing models of community, and I am aware that even in the most progressive areas there is still a majority in denial and unwilling to change until there is no other choice. For now I think those of us trying out various experiments in community will probably have to settle for learning to ‘be together’ before they’ll be ready to ‘do together’ or really ‘live together’. It’s fascinating to watch groups that have achieved this while at the same time being personally reluctant to give up the freedom of living alone with no responsibility to anyone else. Learning to open yourself to loving people for who they are, even those you don’t really like, because they live in your community, are a part of the life on the same land you are, is awesome difficult work. No surprise most of us will only learn this when we must.