Since my retirement, I’ve been attempting to practice being more present. One of the obstacles, I’ve discovered, is that I’m not entirely sure what presence ‘looks’ or ‘feels’ like. I think meditation is a worthwhile practice, but it doesn’t quite capture the full sense of ‘being present’ — that rare and remarkable feeling of being simultaneously relaxed and aware, totally ‘in the moment’. It’s the kind of high-performance state that is needed, I think, to be either an excellent facilitator or an excellent creator.

ee cummings and TS Eliot describe the need for a poet to be in that state of being that is completely attuned and open to what is, such that the creation seems almost to occur through them rather than by them. But they also explain that the craft of poetry both entertains (e.g. through evocative imagery or a clever turn of phrase) and brings new insight or perspective, a new way of looking at things the reader has never considered. To cummings this was a never-ending fight; to Eliot it was the painstakingly hard work of the writer.

It would seem almost impossible to at once ‘be’ in that open, creative state and ‘do’ the hard, struggling work, needed to produce great poetry. I think the reason it seems so impossible is because it is — I think there may be in fact two different states of presence.

The first, which I’m calling ‘Now Time’ presence, is that relaxed, aware, open state of high perceptiveness, imagination and connection in which you are totally attuned to what is and open to what could be. The second, which I’m calling ‘Clock Time’ presence, is the focused, attentive, self-disciplined, synthesizing state in which you are able to bring everything you know to bear to do something extremely competently. You’ve probably experienced moments of both, though probably not at the same time.The first is more a ‘being’ state, a somatic one in which your body is utterly at one and at peace with the rest of the world. The second is more of a ‘doing’ state, a social one in which you are sufficiently attuned to others’ sensibilities to be able to produce something that will resonate with them (though in the case of poetry you may not not quite how it will resonate with different readers). The first lets you sense and feel what is, while the second lets you capture it so others can feel it too.

Both are high-performance states, but they are very different. From studying great writing I have learned that its creation is often iterative, and I’m proposing that it is when some of those iterations are in ‘Now Time’ presence and others are in ‘Clock Time’ presence, that the best writing is most likely to result.

Let’s look at an example. TS Eliot wrote his Four Quartets over a period of years, and there is evidence they were extensively edited and reworked as he wrote subsequent works. Take a look at section I of the first quartet, Burnt Norton, the section ending with:

Go, said the bird, for the leaves were full of children,

Hidden excitedly, containing laughter.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

And now read the final section V of the final quartet Little Gidding, written years later and meant as a completely separate work, which includes the following:

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from… And every phrase

And sentence that is right (where every word is at home,

Taking its place to support the others,

The word neither diffident nor ostentatious,

An easy commerce of the old and the new,

The common word exact without vulgarity,

The formal word precise but not pedantic,

The complete consort dancing together)

Every phrase and every sentence is an end and a beginning,

Every poem an epitaph. And any action

Is a step to the block, to the fire, down the sea’s throat

Or to an illegible stone: and that is where we start.

We die with the dying:

See, they depart, and we go with them.

We are born with the dead:

See, they return, and bring us with them.

The moment of the rose and the moment of the yew-tree

Are of equal duration. A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England.

With the drawing of this Love and the voice of this Calling

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

At the source of the longest river

The voice of the hidden waterfall

And the children in the apple-tree

Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

Quick now, here, now, always—

A condition of complete simplicity

(Costing not less than everything)

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

I would argue that the haunting, stark, playful and beautiful images in this work came to Eliot when he was in a state of “Now Time” presence, while the craftsmanship, the careful and precise choice of words, the brilliant re-statements and circular integration of ideas and images into a cohesive whole, occured when he was in a state of “Clock Time” presence. Eliot claimed that the only way to evoke emotion in the reader of poetry was through the use of images, though whether the emotion evoked was precisely the one the writer had hoped for was not the poet’s business. But images alone are not enough, he wrote, in an essay The Social Function of Poetry:

Poetry has to give pleasure… [and] the communication of some new experience, or some fresh understanding of the familiar, or the expression of something we have experienced but have no words for, which enlarges our consciousness or refines our sensibility… We all understand I think both the kind of pleasure that poetry can give and the kind of difference, beyond the pleasure, which it makes to our lives. Without producing these two effects it is simply not poetry.

These two effects, I believe, require two different states of presence to produce, and what comes to the poet in each of these states must then be crafted together into something that is neither overly sensuous and emotional nor overly intellectual. This, I think, is why poetry of the calibre of the Four Quartets is so rare.

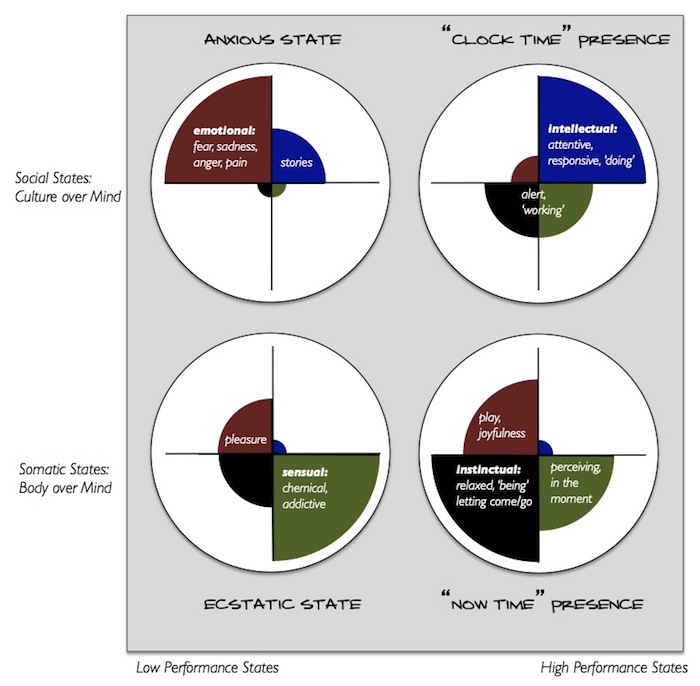

So what does each of these states of presence ‘look’ like, and how are they different? The fact that Eliot’s quartets draw on quaternities (the four seasons, the four elements etc.) got me thinking about Jung’s quaternity and the four aspects of the self: Emotional, intellectual, instinctual, and sensual. I tried to draw how dominant each of these four aspects of self are in each of the two states of presence, and in two more prosaic, lower-performance states: the state of constant anxiety in which many of us live most of our lives, and the state of ecstasy we feel during sex or under the influence of euphoria-producing substances or activities (most of them quite addictive). I’ve reproduced these sketches above.

From this perspective, the two states of presence are quite different, and I would argue it is impossible to be in both of these high-performance states at once. The “Clock Time” presence state (upper right sketch) is the one most of those we have relationships with would like us to be in as often as possible: Attentive, responsive, active, alert, and working unselfishly. This is the state wild creatures shift into automatically when they face a fight-or-flight crisis. It’s amazingly productive, but it’s exhausting and, I suspect, unsustainable. We can’t be “on” all the time. Still, this state allows our intellectual selves to dominate, supported by our sensual and instinctual selves, and, of necessity, we need to subordinate our emotions to the task at hand. We may be effective in this state, but, as cummings would say, we’re not really “ourselves”.

Wild creatures, many biologists now think, spend most of their lives in a “Now Time” present state (lower right sketch). This is the state that, I believe, corresponds to the relaxed/aware state of high creativity I occasionally enjoy: playful, joyful, living in the moment, highly perceptive (rather than conceptive, as in the “Clock Time” presence state). It is a meditative, letting go/letting come state in which our instinctual, intuitive selves dominate, supported by our emotional and sensual selves, with our intellectual selves subordinated. It’s an open, ‘being’ state rather than a directed, ‘doing’ state.

By contrast, most humans seem to spend most of their lives in the chronically anxious state (upper left sketch), dominated by (mostly ‘negative’) emotions, reinforced by the fictitious stories we are told by our culture or which we tell ourselves. Except, that is, for the brief respites we get in moments of sensory-overload ecstasy (lower left sketch) — mostly sex and escapist activities. No surprise we prefer this state to the state of chronic anxiety, even if this state has to be artificially induced and proves to be highly addictive.

Those are my thoughts, for what they’re worth, on what the two states of presence ‘look’ like. The obvious next question is: How do we shift into these two high-performance states, and back and forth between them, more easily and skilfully? I’m working on that, but, paradoxically, I might have to be in those states to figure out how to get there.

Dave – a quick note to say I read every one of your posts with interest. You are a really perceptive thinker and writer. Thank you for taking the time to write up your thoughts for us. I realised I’d been reading for a year or so without saying thanks so here it is!

Pingback: 41. READ. LOOK. THINK. | Jessica Stanley.

Great question, simple answer:

Read “Ensouling Language” by Stephen Harrod Buhner.

http://www.amazon.com/Ensouling-Language-Nonfiction-Writers-Life/dp/1594773823?tag=duckduckgo-d-20

Pingback: What Does Presence Look Like? « how to save the world | e-Development | Scoop.it

Another interesting post, Dave, thank you. What state(s) did you notice in writing the post?

Pingback: What Does Presence Look Like? - Dave Pollard at Chelsea Green