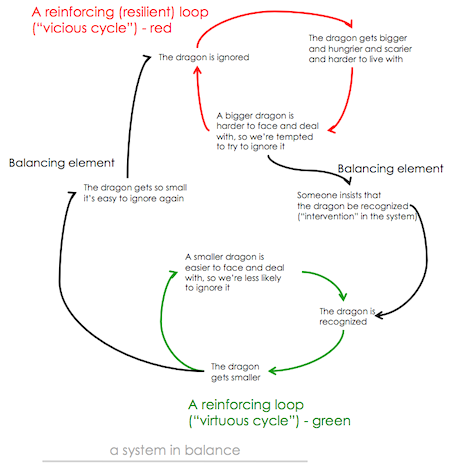

complex system diagram, from this earlier post

Last month I wrote about the 5 “turning points” in my life, the culminations of events and changes in circumstances that caused my life to significantly shift direction.

I have argued before that while we may change our beliefs, our behaviours and our personas throughout our lives, we don’t fundamentally change who we are. The turning points described in my recent article all changed my way of being, and what I did day-to-day and how I did it, but underneath I was (and am) still the same person.

In addition to these situation- and event-driven shifts, there are times in our lives when we suddenly have a realization that what we thought or believed to be true was utterly wrong. We then begin, rather more slowly, to act in accordance with a strange new realization of truth. In my life there have been three such occasions:

- In 2004, after reading over 100 books on human history and culture (16 of which were most influential in changing my thinking), I realized that our civilization was inevitably going to collapse in this century, and that nothing any or all of us could do would change that. Rather than being depressing and paralyzing, I found this realization liberating.

- In 2006, I finally understood how complex systems actually work, and in particular how and why they evolve to resist change. Now not only did I accept the inevitability of civilization’s collapse, I understood why it was inevitable. This led me to coin Pollard’s Law of Complexity. It also made me realize that most of what we try to do in our work lives, in our lives as activists, and even in our personal lives, will really change nothing. Retrospect has since showed me how true that is. Just about everything I tried so earnestly to do, for fifty years, was substantially a waste of time. That’s not to say that I didn’t have an impact, but what had the impact wasn’t my ideas, programs or projects, or really anything I did or created, but rather it was the time I spent with people I loved and/or worked with, listening, supporting, encouraging, suggesting, telling them stories, showing them things, and trying to get obstacles out of their way.

- In 2011 (or so), I finally appreciated that we humans are not in control of who we are or what we do, and that we’re all suffering from Civilization Disease and doing our best to make things better for ourselves, those we care about and the world in which we live (this led to my coining Pollard’s Law of Human Nature). This realization has given me a much more charitable, more empathetic and less judgemental view of our species and everyone I meet. It’s still hard to reconcile with my outrage over the destruction and suffering this collective ‘doing our best’ has wreaked on us and on our planet, but I understand it.

What I find most interesting is that these “sudden” realizations came as the result of years of reading, thinking and learning, so in that respect they weren’t sudden at all. But until a particular moment, a tipping point, had been reached, I was resisting and/or unaware and/or missing some piece of information or insight that prevented this “sudden” shift from happening. Until those moments I was not ready for the shift and would have argued with (or ignored) anyone who had already made the shift.

But once these shifts happened, they then had a profound impact on just about everything else I believed, much of what I did thereafter, and my entire worldview.

What is this process we go through, resisting or oblivious at first to an understanding, idea or perspective, then appreciative but unmoved, and then finally and “suddenly” — aha! — accepting and starting to integrate this new way of thinking and believing into our lives?

Here’s how I think it might happen:

- A profound cognitive dissonance begins to emerge between what we believe and the information, ideas and perspectives we are being exposed to. At first, when we’re exposed to things that don’t conform to our beliefs, we ignore them. We may not even be aware that we’re doing so. But when we start seeing a lot of ‘data’ on a subject, none of which conforms to our beliefs, cognitive dissonance arises. This is especially true if the ‘data’ comes from sources we trust, or if it is put forth in a particularly articulate and compelling way. Passionate well-crafted ‘rants’ and humorous or satirical ‘pokes’ can be particularly effective in ‘unsettling’ us. So can intense stories.

- For awhile, we sit with the unsettling ambiguity and uncertainty of tolerating both our old view and this new view. It’s uncomfortable because it makes it hard to make decisions and even to talk with people about the subject in question. We don’t like this feeling, so we look hard for anything that will resolve it, in either direction. We want to ‘make our minds up’.

- At this point, we will constantly test the new idea against the old across all four ways of knowing: intellectual, emotional, sensory/evidential/experiential, and intuitive/instinctual. The weight we place on each of the four ways will be personal, based on our life’s experience of the reliability of each way. For example, some people are deaf to their intuition but rely heavily on their emotional sense (in fact they confuse it for intuition). For them, a powerful emotional argument will trump everything else, and if it’s in favour of the new idea, they’ll “suddenly” shift. For others, with a more equally balanced ‘decision-making’ process, it will take more than this, probably at least something persuasive in all four ways of knowing, and greater ‘support’ for either the old or new idea in at least three of the four ways. At this point we will “suddenly” sense that the new idea seems right or feels right to us, and make the shift; or we’ll reject it and return to our previous belief. That rejection may be once and for all, or it may be tentative, open to revisiting, depending on our tolerance for ambiguity and dissonance.

So here’s an example:

For most of my working life I believed that things like mission statements, change programs and strategic plans actually influenced and even changed the organizational culture. That is what I had always been told and what everyone around me seemed to believe. I even developed models on how actions focused on people (training, reward systems), processes and technologies could change organizational behaviour in a comprehensive way. The ‘case studies’ and business books backed up this belief.

The first seed of doubt came with my study of something called ‘cultural anthropology’, which suggested the best way to change behaviour was to study it, like an anthropologist studies a human tribe, find the behavioural patterns, understand them, and then intervene in ways that demonstrably shift those behaviours. At the time I had started studying complexity theory and had read Donella Meadows’ essay on places to intervene effectively in systems. I had also befriended Dave Snowden and learned his theories of how change happens in complex systems, and his bottom-up narrative/anecdote ‘probing’ approach to understanding and intervening in complex organizations.

At this point I was wrestling with the cognitive dissonance between my long-held belief in the effectiveness of top-down interventions, standards and motivators in organizations, and this new perspective that the most effective way to bring about change was bottom-up. I had also discovered (from actually applying cultural anthropology with some clients) how much of what gets done on the front lines occurs by workarounds, circumventing obstacles and acting often in direct opposition to what the top-down ‘people’ (training programs and policies), ‘process’ (policy manuals) and ‘technology’ (actions mandated by limits on data input, and rigid performance evaluation system measures tied to salary/rating) programs of organizations were trying to impose. And I learned that ability to deploy these bottom-up workarounds, counterintuitively, correlated with high customer satisfaction, high worker satisfaction, and hence high employee performance assessment (at least by peers).

At this point, I was still intellectually wedded to the old point of view (that top-down interventions work effectively); after all, there were all these case studies and business books that ‘proved’ it! But from a personal evidentiary basis (anecdotal as it may have been) it was compellingly clear that this new point of view (that workarounds are how things actually get done, for the best) was closer to the truth. The cognitive dissonance between what my head said and what the evidence of my senses said was brutal.

It was my emotions that tipped the balance of the argument in favour of this heretical (and dangerous, in conservative organizations) new view. I have always been a shit-disturber, a challenger, a change enthusiast. It tickled me to believe that everything we’re taught in business school about how change happens is wrong.

It still required me to do more probing to be willing to make the shift. I read critiques of case studies and discovered how biased and distorted they are. I studied more about complexity theory. I found a few allies who dared to question the people-process-technology orthodoxy. I realized that in my own dealing as a customer with large organizations, I appreciated and celebrated workarounds and was frustrated and angered at the top-down constraints that not only prevented people from doing their best work, they did not seem, in the long run, to even maximize organizational profits. Who was actually benefitting from this top-down crap? Apparently only the executives who had deluded everyone (themselves included) that what they did was of value, and the consultants, academics and case study writers paid to reinforce that delusion.

With my intellectual resistance overcome, it was now easy personally (not professionally) to make the shift. If I hadn’t been close to retirement, I might have just lived with the cognitive dissonance and shut up about my new belief. I discovered quite a few people who were doing just that, waiting until they could say what they dared not.

So these three stages — the emergence of cognitive dissonance, sitting with uncomfortable ambiguity, and resolving the dissonance by testing the old and new ideas against the four ways of knowing — seem to be involved in the “sudden” shifts we make in our belief systems and worldviews. It’s no wonder we’re averse to such shifts if we can avoid them!

I may now be on the verge of a fourth aha! shift, related to the illusion of self, the way in which our culture reinforces that illusion, who/what ‘we’ really are, and that we are not ‘all of a piece’, but rather a ‘complicity’ of the trillion cells that comprise us. Tied up in that is the realization that there is no ‘separate’ individual, that there is no ‘thing’ at all (processes ‘exist’, not the stuff they appear to happen to), and that time, too, is an illusion. I get this intellectually and it seems to make sense to me intuitively. And because I sense this illusion of self etc. is at the root of my incapacity to deal well with stress and the cause of a lot of suffering (my own and others’), I’m emotionally ‘pulling’ for the shift to happen.

But I have yet to realize most of it experientially. Because I don’t ‘get’ it experientially, I cannot act in accordance with this radical new belief, so I continue to behave as if I ‘am’ this separate self moving through linear time, and dealing poorly with stress. Maybe I never will ‘get’ it. Sometimes cognitive dissonance never gets resolved. Since I tend to use this blog to ‘think out loud’ about these things, I hope it won’t be too excruciating for readers to endure for a while!

This is the hardest and most frustrating shift yet for me, the one taking the longest and the most effort, and the one likely (if it happens) to have the profoundest impact on my worldview, and on how I ‘am’ in the world and what I do going forward. I’m trying a lot of different approaches these days to push past this impasse (if that is what it is), and I’m grateful to be blessed with the time to do so.

And if it doesn’t happen, well, at least now I can appreciate what’s behind the dissonance, and the unresolved process I’ve been going through. Hope this exploration has been interesting to read, and that for some it might be useful in your own shifts.

Hi Dave,

I enjoy reading your blog from time to time. You’re clearly a thoughtful person.

You may be aware, this is core Buddhist teaching you are discussing, i.e. “no self” or Anatta in the scriptures. The way to realize it experientially is through meditation, as the Lord Buddha taught.

Dave, it blows my mind how often, and how deeply, you echo exactly what I’m going through. It’s such a luxury to not have to articulate this stuff myself!

As usual, good stuff Dave and it taps a lot of my buttons.

Here’s an idea. “we” are a bit like Jupiter’s red spot. We are persistent, coherent (as in sticks together) and in the sense that there is a wind shear at our periphery, wherever we may experience that, we are distinct from our surroundings but not separate from them. In fact we cannot exist without them.

Our eddies wont last as long as the red spot but while they do that distinction exists and is real; too effective attempt to break down the boundary results in the destruction of the eddy. But eventually it happens anyway and its constituents are returned to the pool to be reincorporated elsewhere and later on.

Our general distinction is that we appear to have evolved an ability to be aware of that distinction and in the process also built a huge and usually unjustifiable conceptual edifice around it, certainly the edifice itself appears to be more resilient and durable than any individual and while it exists it is too easy to hide in its labyrinth or become so confused that escape becomes too hard and we give up.

As for critical moments, going through one myself right now, having realised with the Hansen paper that, although my thinking has been down a valid line, my understanding of it is so wildly out of scale that I have essentially to start over again. Meanwhile so many of those around me STILL don’t want to hear, despite my rants, despite my humour, despite my trying to remove obstacles for them.

And, possibly because they cannot allow themselves to consider the cause, my current anguish is also being ignored.

Hard row some days.

Hi Earl: Sounds like a good metaphor for a Star Trek episode ^_^

I have seen families where abuse becomes a habit of co-dependence; anyone outside can see the behaviour of the family members as insane, but from inside it seems like the best strategy, or the only strategy. I think that’s kind of like where we’re at.

Thanks for your writing, and good luck with your next self-reboot.

Hard row indeed.

Dave, thanks for the forum, I’ve logged out of FB for a while because I can no longer cope with the fact that nobody among the non-collapse-dealers wants to hear. Checking now to see how long it takes for anyone to notice.

Once I see a hard row, apparently I have to hoe it to the end.

That reminds me of the following I wrote in a newspaper column: “Normal accidents, according to organizational sociologist Charles Perrow in a 1981 article, are problems that arise out of the very nature of complex systems. They usually begin with a small incident – either intentional or unintentional – but become magnified many times over, by many other small oversights, glitches, misunderstandings, misinterpretations, or missteps. They can become crises of overwhelming or even deadly proportions, when the parts of a complex system are tightly linked together in many different ways. Perrow’s classic example was the Three Mile Island accident in the 1970’s.

Perrow argued that what made these accidents normal, is that such accidents are a result of the interconnectivity of the system itself. While individual events may be anticipated and guarded against, the cascading of interlinked events that create the seriousness of the accident cannot be anticipated or prevented. There are just too many different possible connections between elements, too many different ways that things can go wrong. Moreover, the communication or transfer of action from one part of the system to another happens so quickly that by the time a problem has been identified, it has already been spread through the system in ways that are difficult to track.” (Lexington Herald-Leader, December 4, 2001)

Thanks Sue. Good to see other students of complexity out there trying to convey what so few care to hear.

Can’t remember if you are a T.S.Eliot fan or not, but by reading /listening to his poems – particularly Four Quartets – I find I can sometimes learn interesting things about my understanding of what we call ‘Time”