There are a few restaurants I’ve visited in my lifetime that prepare everything so well that you are truly spoiled, for weeks thereafter, for eating anything else. The word ‘spoil’ etymologically means ‘stripped bare, robbed’. So being spoiled is a mixture of blessing and curse: after the initial ecstasy, when you find you have been robbed of the pleasure you get from eating merely mortal food, you almost regret having tasted perfection.

There are a few restaurants I’ve visited in my lifetime that prepare everything so well that you are truly spoiled, for weeks thereafter, for eating anything else. The word ‘spoil’ etymologically means ‘stripped bare, robbed’. So being spoiled is a mixture of blessing and curse: after the initial ecstasy, when you find you have been robbed of the pleasure you get from eating merely mortal food, you almost regret having tasted perfection.

This is true, I think, for just about any hedonistic or aesthetic pleasure. An artist friend says studying Botticelli spoiled him for most other artists. The perfection reduced his capacity to appreciate other, ‘lesser’ works.

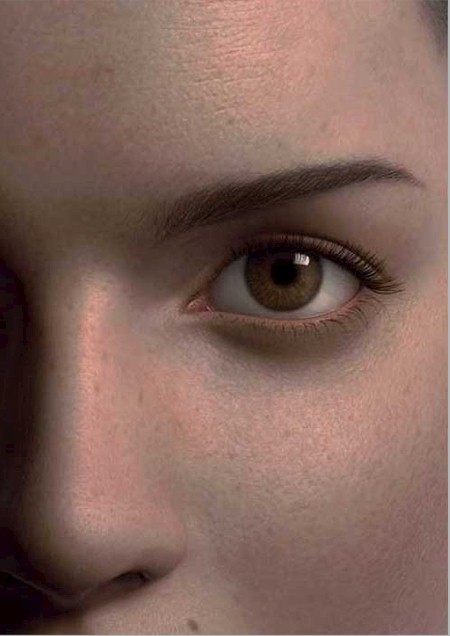

Advertisers and other exploiters in our consumerist culture do their damnedest to spoil us, but in an entirely negative way: rather than presenting us with aesthetically superb, brilliantly designed products, they cloak their mediocre products and services with impossibly perfect branding, usually employing impossibly beautiful photoshopped models in staggeringly beautiful photoshopped settings having unachievably breathtaking, flawless and exhilarating experiences. They shift attention from the imperfections of their shoddy merchandise to us, their consumers, by portraying only perfect consumers in perfect settings doing things perfectly (and, of course, consuming their crap while doing it).

This exploitation has a deliberate, grotesque goal: It strives to make us feel like we’re hopelessly flawed (physically and psychologically), uninteresting, half-alive failures by comparison, so we’re (they hope) compelled to buy their product or service to try to compensate. It deliberately damages us in order to exploit that damage. And it sets an impossible standard for us to strive after, yearn for, and be endlessly disappointed at failure to achieve.

It is not just the sleazy hawkers of products that do this. Employers hold out carrots of impossible perks to attract the most highly skilled and accomplished staff, and to prod them endlessly into working longer and harder (since the promised carrots — the golden promotions, the glory and fame and power and fortune and all the lovely rewards that can be secured with them — are almost always just out of reach). Those extraordinary meals I referred to above were nibbles of such carrots my employers let me taste.

I’m a hedonist by nature, so I’m even easier prey than most people for the temptation to imagine and dwell on perfection. It’s not surprising I was addicted to Second Life, where everyone is flawlessly beautiful and every place is lush and opulent. I am entranced by the perfection of CGI and the hyperrealism of HDR. I have heard musicians play instruments so perfectly or compose works so complex, intricate and brilliant that for a while thereafter I get restless and bored with all the other, inferior music I hear. After spending time in the forest or on an unspoiled beach, I find the city and all its deteriorating constructions and mindless activity unbearable. I haven’t been able to watch a movie in more than a decade because, compared to the rare, best works, the writing, acting and direction are insufferably poor. I’m reaching the same restless point in my reading.

Voltaire said that “the perfect is the enemy of the good”. Have we reached the stage at which imagining perfection in all things (with the help of corporations, Hollywood and others) — perfect looks, the perfect life, perfect relationships, the perfect job, perfect performance, perfect possessions enabling perfect experiences in perfect settings — just makes us miserable with ourselves, those we live and spend time with, and our reality? Is it any wonder so many seek escape in drugs and other addictions (especially the ones that make everything seem perfect, for a while)?

What intrigues me is: how and why did the human character evolve to seek and prefer perfection, even when it is not achievable? It seems a poor adaptive quality to the real, imperfect world.

Here’s a completely preposterous theory, completely unsupported by any evidence (but intuitively appealing), about why that might be. What if it is not the nature of healthy creatures to seek perfection — but rather to seek “the best available”? The best available places to live and migrate to, the best available partners, the best available adornments for ourselves, the best available food, the best available activities. The “best available” implies trade-offs: the best possible place might be too far away, the best possible partner might already be partnered, the best possible food might be rare and hard to find, so we might intuitively seek “the best available” alternatives to this seeming perfection. Without a culture that proclaims that that isn’t (and you aren’t) good enough, and that (with money, or wiles, or effort, or luck) perfection is achievable, the “best available” would seem the happiest and most adaptive strategy. Hoping and striving for more would seem a recipe for suffering, unhappiness and violence. Settling for less would seem a recipe for weakening the gene pool and eventual misgivings.

If this is true, where did we go, evolutionarily, off-track? I’d guess the first problem was the emergence of ideation and imagination, and hence ideology and idealism. Why would anyone become an idealist if they could instead be a realist? If the tribe were under severe stress (caused, say, by climate change, or overpopulation) the short-term reality might be pretty grim, and there might be some solace in dreaming of a better longer-term future. If the stress passed and the species was again thriving in balance with all other life, the idealism would become purposeless and likely cease; why dream of Eden when you live in it?

But what if the stress never went away, but instead became chronic? Then the idealism might become the escape it is for so many humans today. And the unhappiness behind that chronic dreaming of something better tomorrow could be exploited, as it has been, by those who benefit from us never being happy, always wanting more, and striving for perfection.

That’s my theory anyway — we got smart enough to imagine, and then stressed enough to want things to be, endlessly, how we imagined. And all it would take would be a brief taste of perfection — the perfect relationship portrayed in a movie, the zipless fuck in a video, the perfect face or body portrayed in a photoshop makeover, the perfect weekend in a beer commercial, the perfect sunset in HDR — and suddenly nothing real is good enough any more. We’ve been spoiled by perfection, and we never even got a taste of it before that happened.

Image: An entirely CGI character, Aki Ross, from the film Final Fantasy

Makes perfect sense to me.

It is as if the human race has some deeply buried memory of being in a state of perfect harmony that this been lost somehow. What seems to be a aspirational hopefulness and a tendency toward “imagining possibilities” might really be a longing for something that was lost. There are scientific ways of explaining it but I think myths and stories such as the one about the fall from grace, of being cast out of Eden, of being forced to live with the stress of constant toil, of making the earth yield its fruits….is as good a description of the shared human experience as any. Who knows when and where the change happened, but it seems to be it did and now we aren’t like the other animals. I don’t see how a state of grace can be retrieved by smashing civilization, or trying to return to the jungle. Evolution doesn’t work that way does it? By going backward or retracing steps? Civilization is just one of the symptoms of the change toward aspirational thinking. Or so it seems to me…

This is a narrow definition of imagination and closer to fantasy than what I sense imagination truly is. Fantasy is a product of the ego whereas imagination such as with Jung’s active imagination (leading to his Red Book as an example) something other is presenting the imagery to us. One needs to learn the difference. It is the difference between egotistical fantasy and working towards wholeness by following the urging of psyche. The former leads us to the dead end, Thanatos, and the latter perhaps to a sense of Eros and a loving relationship with life despite the ego’s defensive perfectionism.

Excellent comment, Theresa. First rate.

A long history of idealized or perfected forms exists. That’s essentially what Plato’s Parable of the Cave is about, though it’s dressed up slightly differently. In more modern history, both Nietzsche and Spengler recognized that ideals had gained greater currency than the actual, undercutting everyday experience. And that was before the rise of mass media. Now that we’re force-fed surprisingly narrow depictions of perfection through mass media, few or none of which are truly attainable, it’s no wonder that we feel anomie and listlessness, since the false promise of a near-constant succession of perfect moments never materializes.

This also plays out on the optimism/pessimism axis. Forced optimism is a disconnect from reality in favor of hope, yearning, and visualized fantasy, yet we’re encouraged to indulge because under some circumstances it works to keep people striving. OTOH, pessimism is more rooted in reality (a quick survey of just about any historical period ought to confirm that) but gosh, so unpleasant. Better to deny or forget and move on, right?

Both of these are symptoms of what I’ve variously called the “flight from the sensorium” and “living in our heads.” It’s transitional. Once the Transhumanist project of being pure thought is achieved (typically consciousness uploaded into a computer), we can leave behind all the messiness of having a body, with its aches, pains, and needs, and be free to explore without constraints. I have always felt that is merely a projection, much like the afterlife, which like idealized forms falsifies the world we actually have.

Brutus, I never really thought about Transhumanism in the context of non-duality. If we accept that the separate self, “consciousness” (of oneself as separate), and time are all illusions, as non-duality holds, then what Transhumanists would seem to seek is to make that illusory separation permanent. One cannot “transfer consciousness” into a machine (there is no such thing), but there’s no reason why the illusion of separation selfhood couldn’t be transferred into a machine, and inevitable failings of machinery notwithstanding, sustained more or less indefinitely. But while pain may reside in the body, suffering is a construct of the mind of the ‘separate’ self, and hence what Transhumanists would seem to be aspiring to is not liberation from the mortal body but to be sealed in the separate suffering self forever, a permanent hell.

I agree that there is no way to upload or transfer one’s mind into a machine, but that possibility has been bandied about for some time now, and like the Singularity (or collapse), it seems to always be right around the corner or just over the horizon. In the meantime, we indulge in thought experiments that reveal motives and desires shared by a surprising number of us. Others could no doubt correct me, but as I understand it, Transhumanists divide into those who wish to merge into a supposed electronic mind and thus lose themselves (or their selves) and those who wish to retain their selfhood (a virtual self?) and live as free-floating thought within an electronic environment. In the former case, there would be no one there to suffer psychic torments as you suggest; in the latter case, I tend to agree that it would be a hell of sorts, though no more sealed in that being embodied humans. Our intuition may not be commonplace among those toying with these ideas. I suspect others believe liberation from the body and some version of omniscience (partial, perhaps) might be quite appealing.