drawing by hugh macleod at gaping void

I spent many years of my professional life advising small and medium sized businesses. My main advice to them over the years was: have iterative conversations with customers and colleagues about what you and they care about, and how things could be made better, and act on them. As I explained in my book Finding the Sweet Spot, (yes, sadly, it’s now out of print) organizations that routinely do that are much more successful and resilient workplaces, and much more fun places to work.

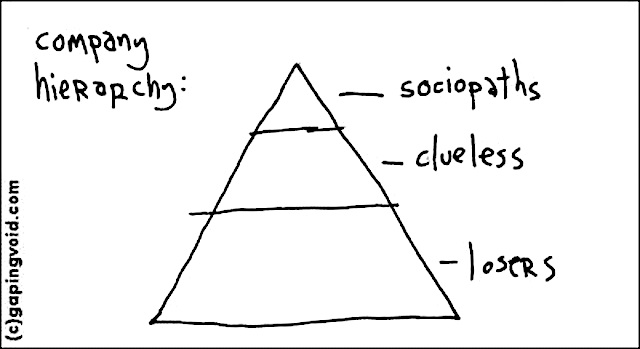

Since retiring, I’ve often found that, in dealings with corporations and government organizations, my professional advice on how to improve products and services has been filed away by the poor underlings responsible for “customer support” or, worse, “customer engagement”. Not because they weren’t excellent ideas, but because the people I spoke/wrote to weren’t high up enough in the hierarchy to get anyone to listen to them. They were generally either new hires or specialists, without the ability to see how the idea would work, and not empowered to forward it on to anyone who could.

This has entrenched my realization that hierarchy is the enemy of learning, and that almost all the brilliant ideas that could be instituted in organizations in both the private and public sector never get heard by the people who have the knowledge to appreciate it and the capacity to implement it. In other words, the best ideas never see the light of day.

The stupidity that created and sustained such hierarchical systems probably stems back to the origins of human organization and even human language. There is considerable evidence that our ‘modern’ abstract languages date back to when humans first settled in one place and required organization to get large-scale work done: agriculture, military/defence, and later industrial processes of all kinds. Just to show how recent this is, anthropologists tell us that we’ve been making art three times longer than we’ve been using abstract languages.

Abstract languages were essentially invented to enable instructions to be passed down from the top of the hierarchy, and evidence of compliance passed back up. Our languages are inherently patriarchal: there is little nuance in our vocabulary, and few words that are without top-down agricultural, industrial or military value. (A read of all but the very best music lyrics and poetry demonstrates that. We have, for example, only one word for love.) It is excruciatingly difficult to contort our language into something that can convey feelings, passion, anything long-term — or anything but the simplest and most obvious changes to the way we do things.

In my work as an innovation consultant, I dealt with the double challenge of (1) managers and workers incapable of seeing how things might be done better differently, and (2) language that, except through the use of stories, made it extremely difficult to persuade or show how things could be improved. So the default is stasis, and the larger the organization grows and the more complex its hierarchy becomes, the more risk averse everyone becomes and the more difficult any kind of positive change becomes.

This is not anyone’s fault. It’s the system, stupid. (Though the system doesn’t actually exist.) We’re all doing our best, and non-hierarchical systems, at least in the current capitalistic economy and competitive social zeitgeist, just can’t survive at any scale. Small is beautiful, and bigger is almost always worse, but in our current industrial society even the most horribly ineffective large organizations will crush small effective ones (except those in niches too narrow for the larger companies to bother with), because the big guys have the money and power to out-advertise, out-produce, price-starve and buy out the smaller ones. Every business they buy and close is a write-off against the massive profits oligopoly guarantees them. And the religion of neoliberalism dictates that even the provision of public goods and services be centralized and made hierarchical for “efficiencies” and “economies of scale” (neither of which actually occurs), and, failing that, “privitized” (under the authority of even larger and less democratic hierarchies). That’s how the system works.

This is true not only in every consumer and industrial sector but in public sectors as well. Ever tried to institute a brilliant new idea in a school or medical organization? These are staffed and run mostly by bright, well-intentioned people, but these people are totally incapable of innovation — they haven’t been given the right opportunity to become creative or imaginative — and are, right up to the level at which they’re beholden to outside political forces, disempowered to institute anything new except on a pilot basis (pilots are good PR and offer the pretence of innovativeness without actually requiring any enduring change), and they haven’t the skills to do so anyway.

I’ve witnessed organizations whose executives knew the choice they faced was radical innovation or extinction. None of them still exists.

There are workarounds that enable front-line people, even in very large organizations, to make significant changes that are valuable to customers, without being sacked or disciplined for violating company polices and procedures that prevent good customer service from being offered. But this is exhausting, and the (mostly young) people who walk that line for a few years get worn out and quit to do work that doesn’t require lying to and disobeying the boss in order to do their job well. Sad to say, many of them face the same dilemma in every job they take, and often end up running their own small niche businesses instead, just so they can look at themselves in the mirror without shame.

As I describe in my book, these small niche enterprises don’t need hierarchy to function and are highly adaptive and (need to be) highly innovative. Everyone in them is listening carefully to customers and colleagues for ideas, and empowered to implement them. Their scale is small enough that they can change quickly. They never have to say to a customer “I’m sorry I don’t have the authority to do that”, and are never forced to shrug off possibly brilliant customer ideas because they haven’t the knowledge, skill or authority to do anything with them.

Over the last few years I’ve offered (based on my own sad customer experiences) excellent ideas to two provincial crown corporations, two of the national telcos, two large financial institutions, and three large educational institutions. They weren’t pie-in-the-sky ideas, but specific, step-by-step detailed process improvement ideas. In half of the cases it took me a half day on the phone to even identify someone willing to field my suggestions. In half of those cases, I gave up — they simply aren’t interested in interaction with customers at all, and see customers as a nuisance and distraction and hire (often offshored or outsourced) junior staff specifically to block customers from talking to anyone further up the hierarchy. None of my suggestions was seen by anyone with the authority to act on it, and mostly I got “thank you” emails telling me that they appreciated my comments while making it clear they didn’t understand them.

The only solace is knowing that these people really are doing their best with the impossible work situation they are stuck in, and that hierarchies of every kind will collapse when the military-industrial-corporatist economy that gave rise to them falls apart. That won’t take long now that real (not the fake ones governments report) inflation and unemployment numbers, massive and soaring corporate, government and personal debt levels, and artificially suppressed interest rates have reached utterly unsustainable levels. No wonder the execs are all buying up land in isolated areas to escape to. They somehow think they’ll be able to support themselves there without cheap, obedient hired workers to do all the essential work for them.

So I’m saying (probably no surprise) that it’s a waste of time trying to reform large hierarchical organizations (private, governments, education, health care included). They’ll be gone soon, bankrupt, and we have more important things to do. Most of those things entail relearning the lost art of community-building, so that, while none of us can be personally self-sufficient, innovative and resilient, our communities together just might.

At the moment, most of us are too indebted to the existing systems (financially, psychologically, and with our scarce time) to even consider anything else. But as the systems get worse (and don’t believe the fools at the NYT and your local politicians citing GDP growth as proof the economy is healthy), the organizations you now think you owe your career, your time, and your mortgage to will start to disappear, and you’ll have both the time and the need to relearn about community self-sufficiency. In most neighbourhoods, there is no cohesiveness and no local essential resources with which to build community, so those communities will eventually become ghost towns; you might want to find viable neighbourhoods that can survive as communities after economic collapse, and consider moving there and taking your loved ones with you. There aren’t many, and once you’re there you’ll start to learn how important community is and what some communities have already started to do.

Once reality sets in, and the problem of a collapsed economy is compounded by unaffordable energy and worsening climate crises, it’s going to be tough for everyone for a few decades or even a few centuries. Talk to those who lived through the Great Depression and you’ll get a taste, except this one isn’t going to end in anyone’s lifetime. Once we’re through it the small remaining human population will likely thrive, though in ways we don’t measure and probably can’t imagine.

In the meantime, when you get frustrated with hierarchy, appreciate that no one is to blame for it, and that it’s unreformable, and do your best to work around it. That’s good practice for the decades ahead. Instead of trying to help these bloated bureaucracies learn how they could do and be better, help those in your community learn what you can do, together, to thrive without the bureaucracies that, for a little while longer, we have to put up with.

great realpolitik, Dave. You just helped me get my head around the pecking orders and the bigger picture. Always worked in hierarchies and amazed at how frustrated people are when we have knowledge we cant talk about in constructive ways. Progress is celebrated while none is made. My friend watches colleagues teach Orwell’s Animal farm while they actually work in one. Some are more equal than others! I couldn’t stand being a wooden top in charge of a system that stifles imagination and genuine “love” for others and making real differences. I’m focusing on community building and heading your wise advise.

Pingback: MWL Newsletter No 80 – Centre for Modern Workplace Learning

I sympathize with your observations but have a slightly different take.

Even ancient tribes had a chief who made important decisions. Organization is essential and organization implies hierarchy. Problems arise when the people at the top stop consulting and listening to their subs. Dysfunctional hierarchy is usually opaque and unaacoutable. Unfortunately, the solution is not to dismantle hierarchy – that leads to worse problems described here:

http://www.cleararchy.com/2017/06/hierarchy-is-inevitable.html

Cleararchy is my attempt to help organizations achieve learning despite hierarchy.

Just realized that’s a pyramid of my ancestry! ;-)