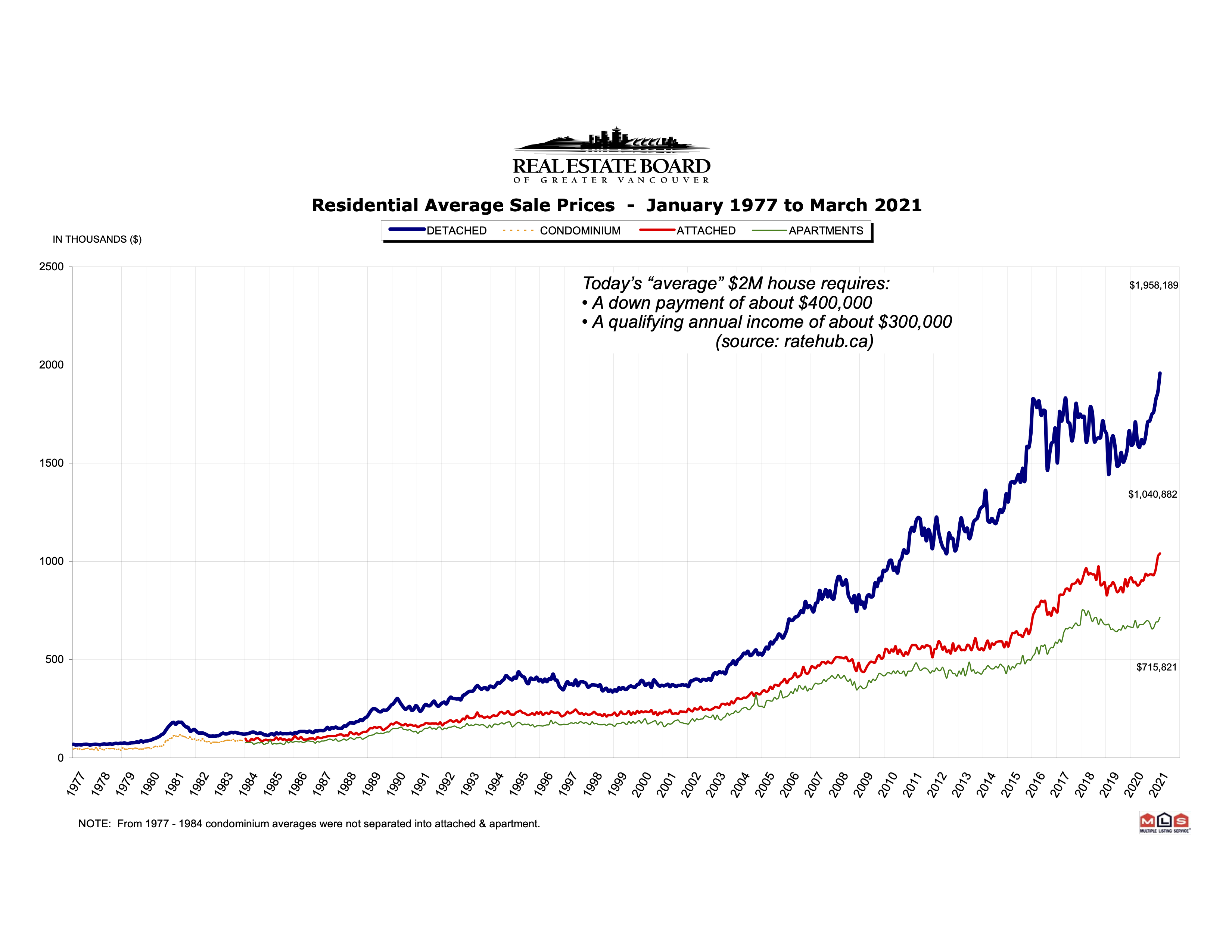

Average home prices in Greater Vancouver. Detached homes now “average” $2M in price. Chart from Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver.

I wasn’t going to write about this — my departure from Bowen — because I was concerned it would come across as sour grapes. I’m only one of many Bowen Islanders who’ve been forced to leave the island due to a lack of rental accommodations, despite the fact hundreds of ‘vacation homes’ here sit empty much of the year.

I had a good run — nearly 12 years before my luck recently ran out. I’ve been heavily involved in volunteer activities on the island since the very first day I arrived — Chris Corrigan invited me to a “future of Bowen” session he was facilitating that day, where I met Mayor Bob and many of the Bowen peeps who have subsequently become good friends.

I want to stress that what is happening here — haphazard development, housing problems, lack of good local jobs, growing and unmet infrastructure needs, and management by crisis — is happening in the ‘exurbs’ near most of the world’s most desirable cities. And Vancouver is regularly in the top 5 lists of the world’s most desirable cities.

I left Brampton Ontario, a suburb of Toronto, in the 1990s because it had changed in just ten years from a city with 40% of its land in Agricultural Land Reserve (and a mayor and council determined to keep it that way), to a city with no agricultural land at all, an endless, sprawling, ‘discount’ suburban bedroom community with no real industrial/commercial base and hence inadequate budget for sensible urban planning or infrastructure maintenance.

Most of its people were there of necessity — it was the closest place to Toronto, where they worked, that they could afford to live. Many had no real ties to the community, no interest in seeing it flourish, just a determination to keep property taxes as low as possible so they could continue to afford to pay their mortgages and live there. A similar tale has played out closer to home, in the relentless development of urban communities like Richmond, Burnaby and White Rock.

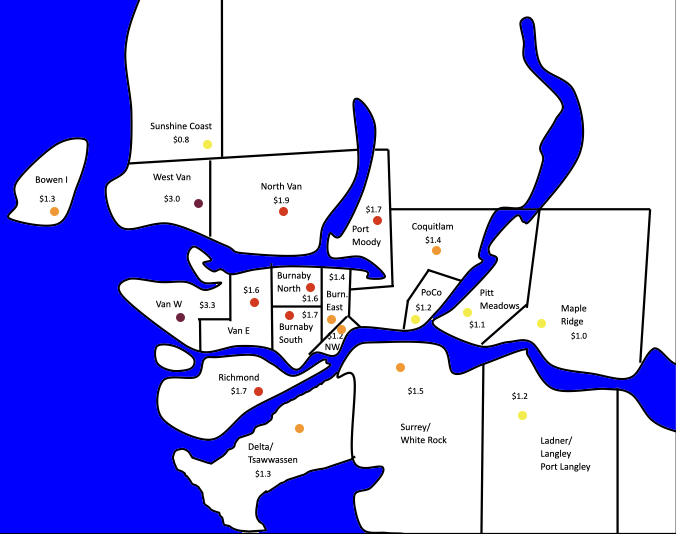

Current “average” detached house price in Greater Vancouver municipalities, in millions of dollars. Purple denotes $3M+, red $1.6-3M, orange $1.3-1.5M, yellow <$1.3M. Data from from Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver.

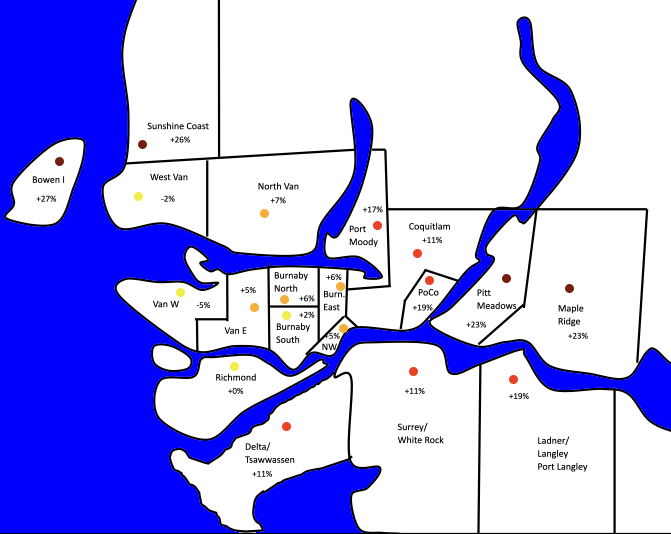

Percent increase 2018-2021 in “average” detached home. Purple denotes increase of >20%, red 11-20%, orange 5-10%, yellow <10% increase over the past three years. Data from from Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver.

It’s not that bad on Bowen — yet. But look at the map of housing prices and affordability in Metro Vancouver and the signs are not good — prices in the exurban areas like Bowen and the Sunshine Coast are rising at twice the rate of the rest of the city, catching up to the city in sheer unaffordability for most of the people who work here. There are already signs that those Bowen Islanders whose health and work allows them to live farther from the city are moving ever farther afield, to the Cowichan Valley on Vancouver Island, and to the more distant Gulf Islands.

Adding to the challenges of living on Bowen is that the list of needed infrastructure projects for our sprawled-out island, with a total cost that can’t be absorbed by our small population’s residential property taxes, is growing to scary levels, making us more and more dependent on federal and provincial government grants to make up the difference, and adding to the island’s precarity. Water is becoming a critical resource, and there is no money for bike lanes on the roads (cycling on the island is downright dangerous), so the island is increasingly dependent on cars, and of course the ferry to the mainland.

Like many exurbs before us, we are becoming a three-tier community: Here, the top tier consists of the ultra-wealthy with their multi-million-dollar (often second-home) mansions. The middle tier are the exhausted commuters preoccupied with preparing for their next ferry trip, and salvaging the rest of their precious time with their often-young families. And the third tier are the largely-subsistence working class and artists, the ones who spend the most time on-island, and who want to support and expand community amenities, but can least afford to do so financially.

A recent study indicated that Bowen Islanders, compared to our North Shore mainland neighbours, suffer from higher levels of anxiety and stress, and are more likely to be dealing with problems of addiction and illegal substance use. They came, many of them, in search of sanctuary, and now so many are forced to leave.

It’s a recipe for failure, but it’s nobody’s fault, and attempts to blame the Muni government for not “fixing” the problem are ill-founded. The problem is worse, for example, in the SF Bay area, as modest exurban homes there are razed to construct monster homes, driving the working population father and farther out. The situation is similar in exurban Toronto, and in many world cities like London and Sydney.

Rents in Metro Vancouver, like housing prices, have doubled over the last ten years, and only an economic collapse will prevent them doubling again in the next ten, further widening the chasm of inequality that has become a hallmark of this century.

Home-owners who rode the market up, quite a few of whom invested in second and third properties with low-interest mortgages before prices soared, are now mostly renting those extra properties out not as single-family dwellings but as two- or three-family dwellings with newly-constructed separate entrances, to get a decent combined ROI from all their tenants. In the most desirable areas, single-family homes are now mostly rented as “executive homes”, often for $10,000-$50,000/month, to corporations who (unlike us) get to write off the rent as a business expense, and which allows them to provide a perk for their six-to-seven-figure-income visiting execs at the same time. Or rented out as AirBnbs for $350+/night.

This is, of course, an unsustainable situation. Those who have ridden the market up to the point they now own their homes outright will probably be able to stay here, but their new wealth is fragile and only on paper. Their kids won’t be so lucky, unless they move back in with the folks and wait to inherit the family home. But there is a lot of global money looking for beautiful cities to invest in, and that money will continue to push prices up, so that as residents leave or die, there will be only two choices for places like Bowen: Subdivide, turning most of the Cove into multi-family dwellings and possibly Horseshoe Bay-style highrise waterfront condos; or sell out to rich property owners and developers who will tear down the small homes and convert them to luxury accommodations for multi-millionaires.

In my early days on Bowen, I dreamt of a third alternative: The island being declared a model “eco-village”, with severe restrictions on development, the use of conservation development principles, and piloting of projects for local sustainable living that could then be copied by other communities. Or else I thought Bowen might evolve into an artists’ colony of sorts, a creative focal point where artists and crafters of all stripes could meet and collaborate, much as they did in the island’s Lieben days, and where a combination of large-scale public funding for cultural projects, initiatives by studios and arts foundations, philanthropic ventures and new-media arts and cultural institutions would make Bowen a hub for the creative industries, a kind of small-scale Silicon Valley for the right-brained.

But I no longer see these as real alternatives. The fiercely libertarian streak of some of our residents, expressed through their defeating the national park plan in a referendum, their opposition to the “controlled by outsiders” Islands Trust (regional ecological preservation governance body), and their resistance to zoning limitations, suggests we aren’t ready for such a radical vision, or for the sacrifices (both financial, and in the personal ‘freedom’ to do whatever we want with ‘our’ private land) that such a vision would entail.

So we are just kind of flopping up every which way, allowing the market and the zoning variance requests of the moment to dictate much of our dialogue on the future we want. We have a wonderful, aspirational Community Plan, but in the face of development demands it seems to me now a rather toothless document. Chain saws, logging trucks and construction vehicles straining up our hills now often drown out the natural sounds of the island. We can say how many people we’d like to have living on Bowen, the diversity we’d prefer, and the principles by which we’d like them to live, but we really have almost no control over it, and the development pressure will only get worse.

I think we, the citizens of Bowen, really tried to create a better vision, a better model of how to evolve a sustainable, human-scale, somewhat self-sufficient community. But the power ultimately rests with the property-owners and developers, and they have outgunned us at every step. To much of the development industry, ‘underdeveloped’ communities are viewed as just corporate enterprises to be clear-cut, liquidated, squeezed of as much cash as possible, and then, having been sold off to private landowners at the highest possible price, abandoned as attention shifts to the next ‘underdeveloped’ place.

And our backwards provincial government still aspires to log 40% of the island, which only a massive expression of outrage by our community has prevented so far; “we’ll be back in five years” the government timber corporation promised.

The residents of the island have limited power and money to realize any grandiose vision, and therefore I think Bowen will inexorably evolve into some combination of multi-millionaires’ playground, retirement sanctuary (for those pension- and property-rich enough to afford it), and grinding commuter bedroom community. The underclass of workers and artists will be slowly forced out, as mid-six-figure down payments and mid-six-figure qualifying incomes become the only ticket to becoming, and staying, a Bowen Islander. Like so many other exurban communities that are sitting on “the next closest available land for development”, our intentions and dreams will be noble but they are unlikely to be realized. That’s a shame, but no one is to blame — the market forces unwittingly smashing our dreams of exceptionality are relentless, indifferent, agnostic — and global.

What will be a small and bitter consolation for many of us is that, unlike the fools in the Joni Mitchell song, we really do know “what we’ve got”, even before “it’s gone”.

My new home, Coquitlam, has been largely paved already, and developers are now pushing new developments up the mountains and coveting the precious tidal lands to the east — including the world’s largest tidal freshwater lake, home to thousands of wild species. Property-owners in the hills leading up to the area’s gorgeous Crystal Falls have blockaded the trail leading to the falls, on the basis that, as it traverses private property, the public has no right accessing this natural wonder. The government is stymied, apparently hoping the problem will somehow go away.

So it’s the same all over, but at least, for now, there are still places for dreamers like me to rent there.

So I’m off, but I will continue to do volunteer work on Bowen as long as my Bowen peeps will have me. I already sense my continuing presence will be something of a constant nagging reminder of Bowen’s incapacity to hold on to some of its most passionate and diverse residents. But it will unfold as it does. I’m not angry, or surprised, at what has happened.

For nearly 20 years, I’ve been keeping a blog called, with tongue firmly in cheek, How to Save the World. Its subtitle is “chronicling civilization’s collapse”. It doesn’t propose any magical solutions, since I am increasingly convinced there are none. Yet I remain a self-proclaimed joyful pessimist, and I have no regrets. It’s an amazing time to be alive, and all we can do is our best, with what we have to offer, wherever we are.

I will be forever grateful to the people of Bowen Island for making me feel so at home this past twelve years. I salute you, and though I’m leaving, I’m not going away. See you around, my friends.

In Part Two of this “letter”, I want to talk about what it takes to be a real community, in an age when urban areas seem to have only disconnected and anonymous “neighbourhoods” instead. Most of what I’ve learned about community I learned from fellow Bowen Islanders.

From Google Maps, it looks like the farms along the Pitt River are next in line for development, particularly the big blueberry farm (or perhaps they are all subject to flooding, which would save them).

Since the world won’t be saved and collapse will include a significant amount of human depopulation, there will be plenty of places to live after collapse. But most of those places will be too far from ag land to survive on, and urban pavement is too hard to remove just to expose a little gardening soil. Asphalt might be broken up for heating fuel and that will help a little, but not much.

The vast majority of existing housing infrastructure will deteriorate while empty. A little will be broken down for building materials to construct dwellings elsewhere, but most of it will just rot or rust. Abandoned cities will be the wonders of the future, but most people will never see them since there won’t be any good reason to go to one.

In the future, the most valuable housing of all will be large “McMansion” style homes on rural gentleman farms and in resort areas with lots of golf courses. They will provide housing for many families while they provision themselves by working the surrounding land. The houses won’t have electricity but they will keep the rain off and the wind out.

And the sheltered area of some modern homes is nearly equal to that found in historical small farming villages. So rural subdivisions of five acres or so, each with a big house, will be an investment in housing for future subsistence farmers. Rural sprawl may therefore be preferable to the dense urban housing often touted as saving open farmland. If sprawl happens, it’s one of the few silver linings to be found in real estate development these days.

Sorry to read that you have been uprooted and hope that you find continued happiness in your new location.

Dear Dave,

I send my very best wishes for your new life in your new community.

You have enriched my life on Bowen by your presence and your insightful contributions of words and pictures in this blog. Your bird pictures always helped to lift my spirits and make me glad to be alive. May there be many friends and wild beings in your future.

Susan Matthews

As a former islander, I know the sense of loss as you move back onto the continent, Dave! All the best in Coquitlam!

Ahhh… the truth will out! Your tongue has been firmly planted in your cheek as you write this blog. I suspected as much. Some of us who share our musings on the internet run tests to see whether or not people are aware. I find that I am artificially bombastic for the same reason. I want to see if my conversation partner is actually paying attention to the topic.

Well, it’s interesting to hear about the big changes to your life. I drove up through British Columbia a few years ago, and was surprised to find that the tourist communities had the opposite vibe of those I was familiar with in the Colorado Rockies.

I moved away from my town of Durango Colorado, years ago – and it has had some really hard times in the past couple of years, even before the pandemic. It’s been facing a serious bout of ennui. I think that as you say, the problem is that newcomers to the town don’t recognize that the economy runs on the creatives who settle there… they run the art galleries, they act in community theater, and they volunteer in the schools. In short, the property values can only rise in direct proportion to how these people add value to the community.

There is a great skit which I always love to watch, here:

https://youtu.be/hgYwTELj-fs

Creatives are important, but an often overlooked resource. There has, as a result, been a lot of chitter chatter in Durango about affordable housing. And this has led to a trend of inviting a growing transient population of young men into the community who really have no personal investment in the town, or respect for the values that we hold dear. I have even worried about the risk that the community might end up like the Florida Keys. The community has a heart of gold for young men just like the Keys had a love for ethnic minorities when the Beach Boys took an interest in them and it inspired them to write the song Kokomo, but you have to demand certain standards of conscientiousness.

Personally, I think that the secret to keeping a community flourishing is that people pay attention to the kids. I have seen communities which resolve not to do this, like one of my favourite cities on the West Coast – Portland Oregon – suffer decline when the grandparents feel that they cannot wistfully look at the neighbors’ kids in the park.

To the extent that kids have an interest in strangers, child abuse declines dramatically. It just makes the parents think twice, when the kids start being eager to talk about the characters of the community.

Flourishing kids means the future of the community is bright.

Thanks for the comments and good wishes. And Christopher, thanks for the interesting thoughts towards Part 2 of this post, on community. It’s interesting to see the disconnects between generations and between ethnic groups living and working alongside each other but operating as if they existed in different dimensions. I’m trying to understand why that’s so, but the best I’ve come up with so far is that the different age/cultural cohorts don’t understand each other, and what we don’t understand we tend to fear or at least distrust. That has serious consequences for a neighbourhood’s capacity, when things get tough, to act as a true community.