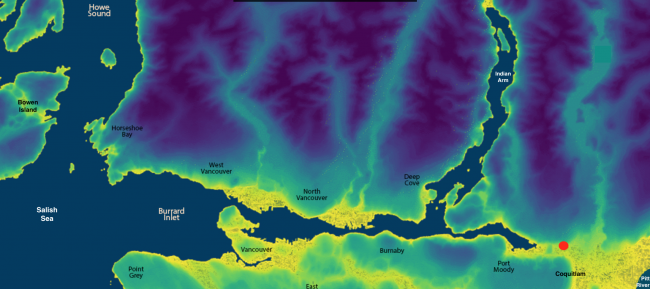

topographical map of the Burrard Inlet, image from UBC

what will become of those who cannot learn

the terrible knowledge of cities

— Richard Shelton, Requiem for Sonora

When I lived on Bowen Island, I could look out my window and sometimes see no human artifacts at all — no lights, no buildings, no power lines, no roads. Just forests and mountains and sea.

All human constructions, now, strike me, at least in the grey light of day, as shabby, ugly, and a bit sad — even (and sometimes especially) our most expensively designed creations. Try as I may, I cannot see them with the eye of a crow, who looks at everything indifferently as beautiful, wondrous. Who sees rust and ruin as curiously and impassively as water droplets on leaves, gleaming in the sun.

It’s cold, but the bright sunlight of midwinter beckons me out, to wander these still-unfamiliar streets of my new home in Coquitlam, and today I’m drawn to walk to the easternmost point of the fjord that we call Burrard Inlet (First Nations name: səl̓ilw̓ət, pronounced “tsleil-waut”, meaning, of course, “the fjord”). As I walk, I’m aware that all the land from my home to the mudflats of the fjord was deep beneath the Salish Sea a mere 10,000 years ago (when humans already haunted this land).

In those days, this fjord, the centrepiece of an area now home to almost three million humans, was twice as long, reaching to what is now Pitt Lake. In those days, the mighty Fraser River flowed into it, and we humans were mere bit players in a land of whales, orcas, and salmon running so thick you could grab all you could eat without a net or hook.

As I walk, beneath my feet are the relics of marine life. We are harpoon-dodgers, all.

I wonder at humans’ gullibility and herd mentality. We seem gripped by a form of recurrent collective madness. The media, and people across the political spectrum, are making the same mistakes in the drumbeat for war in Ukraine that they made in Iraq, accepting zealously the simplistic lies of the PR spinmeisters. Of course Putin is no saint, but the situation in Ukraine is complex and horrific and there are no “good guys”. Already the media are saying “Is Taiwan next?”. It’s insane. We want to risk nuclear war for this?

But of course we have no choice. After all, it’s a chance for polarized westerners to pretend we’re all on the same side for once, and it’s a desperately needed distraction for bumbling western politicians. We’re all up on stage reading the lines our conditioning has dictated that we read. We can do nothing else. It’s pathetic, but that’s where we are.

I arrive at the mudflats, and I am immediately greeted by hundreds, perhaps thousands of crows, as loud as anything I heard in Still Creek, but this is just a staging ground for their afternoon commute to the roost. The mudflats have, it appears, designated areas for crows, for ducks (mallards and mergansers mostly), for seagulls, for herons, and of course for geese. Few birds cross the invisible territorial lines, but everyone seems happy. It’s low tide. The mud, up to a foot thick in places, lies on a bedrock of sand and silt, and is dangerous for humans and others with un-webbed feet, so the birds have the vast flats to themselves. Unlike my species, these creatures seem to know how to enjoy doing nothing.

Alice Munro once wrote: “The complexity of things — the things within things — just seems to be endless. I mean nothing is easy, nothing is simple.” I think about this in the context of the dawn of another proxy war between NATO, Russia and China. I think of it in the context of climate collapse, and the ghastly and unnecessary toll of the pandemic. None of it is simple, and, when you realize that, none of it makes sense.

I wonder if the key is to try not to insist on things making sense. Why should they? What kind of hubris is needed to insist that everything can be known and understood?

But we have no choice in that, either. We do our best. We do what we’ve been conditioned to do, what we “have” to do. And if that means more brutal, pointless, staggeringly expensive wars, well, then, that’s what’s going to happen.

I try to shrug all this off, but it’s hard. You can know something, but it doesn’t stop you from wanting to ‘un-know’ it, wishing you didn’t. Wishing it were simpler, more valorous. Wishing that everything were moving in an inevitably positive direction.

Before the ice age, the Canadian and American Gulf Islands, including Vancouver Island and Gwaii Haanas, all the way up to Alaska, were part of the mainland. What we now call the Salish Sea was just a northern extension of the Willamette Valley that runs all the way down to southern Oregon, before the Salish Sea was created by the advance of two-mile thick glacial ice. After the ice’s retreat, it took another 1,500 years for the earth to rebound to today’s land/ocean borders.

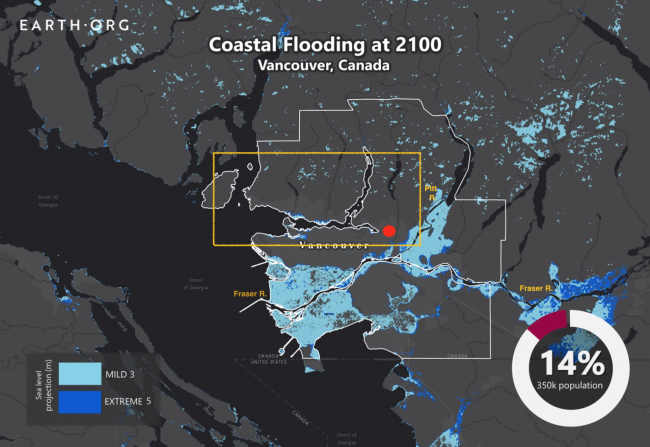

And it will likely only take decades before arctic and antarctic glacial and ice-shelf melt drives sea-level up so it reclaims all of the Fraser and Pitt River valley lowlands, and turns today’s Vancouver into a series of rugged, un-arable islands, lakes and marshes.

projected flooding by 2100, middle sea level rise scenario, per earth.org; yellow line is the Burrard Inlet area from the chart at the top of this post; white line is Metro Vancouver boundary; red dot is where I live now

Last November, the record rain and wind from “atmospheric rivers” collapsed or threatened many of the fragile human structures (dams, weirs, and pumping stations) designed to hold back the waters in southern BC. Sumas Lake, in an area just east of the city, was drained a century ago to create the farmland that produces much of what we in the city eat. As the riverbanks flooded, there was a fear that the lake could be quickly flooded back to its natural state. This was only avoided because of two unlikely strokes of luck (the holding of an abandoned, flooded Fraser River pumping station, and the return of the swollen Nooksack River to its pre-storm course to the sea). As many as fifty thousand people in the area were poised to evacuate. Even with this luck, the flooding created a nightmare of pollution and destruction that will take years to recover from.

Especially during climate collapse, we mess with nature at our peril.

I want the young child’s eyes, the birds’ eyes, that just look with awe and equanimity at everything without judgement, without trying to imagine everything as other than, “better than”, it is. We have only been on this planet for a flash in a hawk’s eye. We don’t know how to make things better, only how to build castles in the sand and then shrug when the tide comes in. We don’t know any “better”.

There is a rather sad-looking little beach on the park at the northwest corner of the mudflats, just above where they deepen into open water, where expensive homes and industrial plants take over the shoreline. But the kids there were playing delightedly in the sand as if it were 20ºC instead of 0ºC. Like me, their parents, pacing restlessly between the children and the birds, seemed caught in a different world from the one that was right there. Ours was an unreal place, one of too much ‘me-ing’ and not enough being.

Over the next six hours, the tide would be rolling in, and the fjord would be, everywhere, as much as four metres deeper. The mudflats would be replaced by shallow water, a place for creatures with gills, and creatures lighter than seawater. The sun was setting.

+ + + + +

Back home, and dark has fallen. The austere skyline of grey cement and steel, with its winter backdrop of dark green coniferous forest and jagged snow-topped mountains, has given way to a dazzling profusion of soft glimmering lights. My world has shifted from ponderous to magical.

I’ve often quoted the advice by John Green’s friend Amy Rosenthal to pay attention to what you pay attention to. Of course, I don’t believe we have any choice in what we pay attention to, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t useful to notice what those things are, and aren’t. In my experience, one of the things that has a major impact on what we pay attention to is light — not just its brightness or colour but its tone, its directions and angles and shadows and edges, its nuances, how it communicates with us, draws us or repels us, and how it touches us in subconscious but powerful ways.

[painting by BC artist Terry Kolber]

My favourite works of art, for example, all use light in ‘striking’ ways, which is remarkable given the limitations of most art media. They ‘draw your eye’ to pay attention to certain things, and then to other things. When I change the light in this room I’m sitting in, it changes what I notice, what I pay attention to. My relationship with light is, as I’ve said before, a kind of conversation. The light bouncing from its source to what I’m looking at, and then to my eyes, conveys and produces a gamut of emotions. There is a reason we call it the ‘play of light’. Interior designers, and theatre lighting technicians (“gaffers”) know all about this.

At night, I think, the neurons that process all these ‘conversations’ are less overloaded than they are in bright daylight, so the nighttime conversations are more like quiet one-on-one chats and less like everyone shouting for attention at a press conference.

At any rate, since I’ve started paying attention to what I pay attention to, I’ve found that I notice more, and that I am less concerned with making sense of, thinking about, knowing about, and remembering things. I’ve found that time seems to pass more slowly. And I’ve found that in my moments of greatest enjoyment and connection, what I am paying attention to are simple things, sensorially rich things, ordinary things, and what they are ‘telling me’, without me thinking about them and what they represent or ‘mean’, without words.

Things that I never noticed before.

Beginner’s eye, then, perhaps, more than beginner’s mind. The eye of a bird, or an artist, or a small child. Just noticing, not trying to make sense of it. Not a bad perspective, I think, for a lost, scared, bewildered person who is quite content, at last, to be old.

Beautiful. Thanks.

I really enjoyed this journal entry. The only thing I’d like to share is to wonder whether you need the last word, “old”?

Brilliant Bob. But if I removed it, I’d have to add “just” as the second last word. And there’s the rub!