This is a bit of a theoretical exploration. I had to write it out to make sense for myself of the two complex articles it attempts to summarize, so I thought others interested in the theory of politics and power might find it interesting.

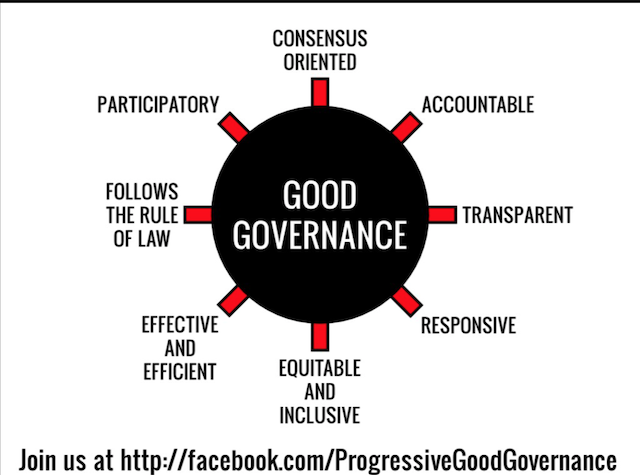

This is how it’s supposed to work. From flickr by Occupy Posters (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Over the past few days, Rhyd Wildermuth has been exploring the subject of political collapse and the history of human governance, drawing in particular on a summation of Carl Schmitt’s political theories by the arch-conservative historian NS Lyons.

This article is an attempt to summarize these two extremely long articles, and figure out what they might mean for our current situation. The basic argument is, I think, as follows:

Throughout the history of civilizations, governance has always been about power — who has it, and when and how it should be used. Civilizations in order to function need an acceptance of a hierarchy, and authorization of those in power, to maintain order. Without it, chaos and anarchy would prevail and these civilizations would inevitably politically collapse.

For most of our civilizations’ history, that power was vested in the gods, and in their chosen representatives — the shamans, the clergy, the emperors, and the royalty. These representatives acted on the will of the gods, with whom they were in direct communication, and hence had the “divine right of kings”.

Most of our civilizations’ wars and crusades were thus ideological, internecine battles between different groups who claimed they were the ones that spoke for the god(s) (singular or plural). These were absolutist battles between ‘good’ friends and ‘evil’ enemies.

Attempts to introduce secular and representative governments were a direct confrontation to this arrangement of power, though they existed side-by-side for much of our more recent history. They are, it is argued, inherently weak, since under them power is supposedly granted from below, by people who never really know with any finality what they want, rather than vested from above, by gods who are omniscient.

Carl Schmitt (an advisor and supporter of Hitler) claimed that such secular governments can survive only to the extent they retain the power of exceptionalism — to impose executive orders that suspend democracy, by a kind of resurrected ‘divine’ right, as ‘custodial dictators’ when the circumstances require it (a ‘war on terror’, for example). A tacit pact must always therefore exist between the ruling government which provides security for the masses in any large society or state, in return for obedience to those rulers.

If obedience is not forthcoming, Schmitt argued, anarchy and collapse of the state is threatened, and then the government’s duty is to suppress the disobedience by suspending the laws as needed, decreeing the disobedient to be ‘enemies’ of the state, and destroying them, in the interest of restoring and maintaining order and security. Just as the gods once ‘smote’ enemies directly so that good would triumph over evil.

So, as we have seen in countries where drug lords, criminal gangs, kleptocracies, robber barons, corrupt corpocracies, and religious fanatic groups (Taliban etc) are actually in a better position to provide security to the citizens than the elected government is, the citizens will quickly pay fealty to these unelected powerful groups instead, as long as that makes them feel more secure.

Rhyd argues that what we’re facing now is a situation where governments think they can and must invoke emergency and executive orders to maintain authority and order, while the citizens have come to believe that governments should have no such authority — that all authority must be the will of the people, and that executive orders, like CoVid-19 mandates and undercover wars and decrees on universal ‘rights’, are a violation of that authority.

The problem is that, while many agree with this, they disagree on what exactly constitutes a violation of government authority. Some see CoVid-19 mandates as essential to the health and safety and hence security of the citizens, while others see them as tyranny. Some would see the ‘secret’ CIA bombing of the Nord Stream pipelines as essential for the eradication of enemies of the US and its vassal states and the maintenance of global order and security, while others see it as a blatant and indefensible war crime.

The question, then, is: How, if at all, can secular governments survive in the absence of any consensus on who the ‘good’ (friends) are and who the ‘evil’ (enemies) are? Especially when modern technology enables propaganda, mis- and dis-information, censorship, surveillance and mass oppression by whoever happens to be in power against whoever happens to not be in power.

Complicating all this, Rhyd argues, is the belief by many religious fundamentalists that the collapse of this unstable, corrupted civilization is actually a good thing, since it will usher in a ‘rapture’ of some kind or other, where the gods will save them (in their current or future lives), smite the ‘bad’ guys and disbelievers, and restore the ‘natural order’ of the gods. All of this generally presupposes humans to be inherently evil, flawed sinners incapable of governing ourselves.

This is radically opposed to the more recent but some might say equally religious view of an equally large number that we are inherently good, that the ‘natural order’ of things is an unsteady but inevitable ‘progress’, and that technology is speeding us along that trajectory.

_____

My thoughts on all of this:

There is a tendency here for us to see our current situation as rather unique — an unprecedented struggle everywhere in the world for power over the ‘other’ groups that are seen as threatening to destroy everything we believe in.

But I would instead see this as just a change in the geographic playing field of similar struggles that have been with us since the dawn of human civilizations. Whereas at one time crusading armies conquered the enemy by marching on and occupying their territory, and either killing them or ‘converting’ them, today the opposing forces are right in our midst.

So what is unique, today, I think, is that the planet is now so crowded with humans that instead of homogenous tribes and nations of similar-thinking people warring against each other along their borders, our ‘enemies’ today often live right among us. The ‘winning’ side can no longer just redraw the borders to show how good conquered evil. The red-blue map, for example, is no longer two solid blocks of colour with a Mason-Dixon line between them, with largely-unopposed (at least, unopposed by those enfranchised) governments in power in each area.

In fact, all over the world we have seen such a fracturing of beliefs in every small geographical area that we can no longer Balkanize our way into separating the combatants. Even a ‘civil war’ is impossible, because the opposing sides, while living in their own psychological and religious worlds, walk the same streets and live in the same communities, largely indistinguishable from each other by their dress, language and practices. Segregation, at every level, almost never works.

We saw in Rwanda where this can lead — during the 1994 genocide, Rwandan Hutus slaughtered nearly a million fellow Rwandans, mostly Tutsis and Hutu ’sympathizers’, and mostly with machetes. These two peoples are virtually indistinguishable in appearance, and share the same languages and religions, and live in the same communities. Some Catholic and Protestant church leaders egged on the Hutu murderers, using their pulpits and broadcast media, falsely portraying the Tutsis as un-Christian ‘foreigners’. Many observers trying to keep the peace were severely traumatized by the sheer ferocity of the slaughter, often neighbour-against-neighbour.

Some would say that humans are just inherently xenophobic (and there are some interesting evolutionary arguments as to why we evolved that way), and that the only answer is homogenous tribal communities with clear geographic territorial boundaries between them, and resigning ourselves to constant skirmishes over those boundaries. Others would blame more recent phenomena like the new media, or new technologies, or overpopulation, or new religions, or ‘evil’ leaders and stupid/complacent followers, for the kinds of ideological polarization that seem poised to erupt into violence almost everywhere.

I have no idea myself. Human civilization has evolved the way it has, and I don’t think it has to be logical. Nor does it have to be inevitably leading in any particular direction. Most changes are cyclical, not linear. “History may not repeat itself, but it rhymes.”

The important thing, to me, is that we simply don’t have any time or energy to waste on ideological and philosophical and religious differences and the resulting wars and violence. Our world is on fire, and the industrial economy that spread the conflagration is poised to collapse.

But it seems likely to me that, since our ideological differences are more visceral, more relatable, and more emotional, to most people, than the heady abstract stuff of climate change and economic fragility, we will continue to pursue our wars, our coups, our bombings, our propaganda, our oppression, and our xenophobic hate, even as everything continues to collapse around us.

Is that just the way we are? Can we really not help killing each other, and in so doing accelerating the damage to our planet and its climate, at the very time collaboration on dealing with our shared crises is so desperately needed? Over any period of time longer than a century or two, are we just incapable of governing ourselves in any kind of democratic way?

These are rhetorical questions. But political theorist Rhyd and historian NS, from opposite sides of the political spectrum, put forward a pretty compelling case that the answer to all of them is ‘yes’.

There is NO CHANCE that well behaved institutions can be designed, be they left, right or otherwise.

We are going to witness such a failed “experiment” very soon, we are actually right in there NOW.

Democracy? What a strange concept.

Who ever invented such a social organization beast?

It’s nowhere found in nature. Even in those societies that call themselves democratic, it doesn’t really exist. The ruling elites don’t give up power and profit. Democracy is a neat trick to manipulate the masses so that they become deluded in believing that they really can participate in the power game.

As long as there are plenty of resources to give the masses bread and circuses, tyrants, dictators and “democratic” rulers can get away with anything.

Now that net energy is declining and the masses (now 8 billion in the aggregate) won’t be able to get sufficient bread, the game will change dramatically. Tyrants, dictators and “democratic” elites will have to find different ways.

But there are no different ways that haven’t been tried before. War and collapse, this time on a truly global scale, will make (fake) democracy and other forms of societal organization obsolete.

Maybe “true” democracy, as practiced by the San and other small small hunter-gatherer groups can become popular again, or maybe not. Maybe there will only be chaos.

Thanks Dave for your constant reflections and questionings; a natural healthy process which although uncomfortable at times, brings us clearly in contact with ourselves and our feelings about mental constructs.

In Times of confusion where truth is mixed in with all the distortions, we should at least be reflecting upon our inner state of comfort and discomfort so that we can maintain some sort of personal coherence. Sit with it regularly so that we can be more semi-comfortable with that as a reality rather than deny anxiety.Things don’t have to ‘make sense’ necessarily as the predominant sense stimulation we have all received is mental and linear while our natural gut feelings and a sharing of them, has become uncommon. (relegated to political representation)

Humans are part of a biologic, evolutionary ‘system’ which has its’ own rules and tendencies which are hierarchically more relevant than our mental constructs where our mind follow our body or mostly suffers the effects of our body(mille-seconds make a difference). History is vitally important to know and to study as it repeats itself and can help reflect the light to us differently. In times of change and emergency, the ability to let go of ‘reality’ or the sinking ship can be vital and uncomfortable, but life into death, into life is this universal manifestation we are imbedded in. Our biggest problem now is sifting through all the lies, as they have become a dangerous habit. That’s why we have seen the dominance of narcissist governments as theoretically their light would save us. If there is a leak in the boat, we must all be sure where it is so that we can apply our minds and bodies to the task. If you don’t know, then sit quietly, as within the quiet, somehow we also can know. If you have not the habit to act (learned to rely on democracy like your mother to care for you), then now is our time to act.

If there is a storm outside, put on your hat and coat when you go out and check if there is wind or rain. In the streets, we will meet others and in our hearts also, even if we stay at home. Solid state paradox time. Regards Pete

homogenous tribal communities with clear geographic territorial boundaries between them, and resigning ourselves to constant skirmishes over those boundaries

Exactly. This had been the state of human affairs for many tens of thousands of years prior to the invention of the state. The sooner we get back to pre-state tribalism, with appropriate population levels, the better. Perhaps this century?