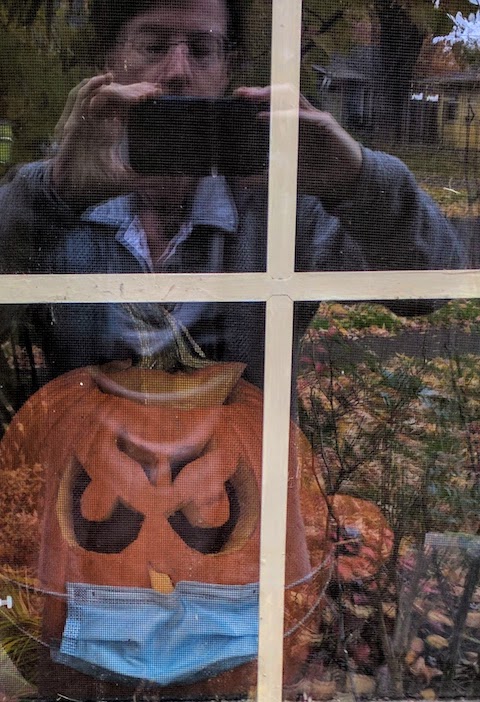

image by amira_a from flickr, via pixhere, cc by 2.0

Several people have recently asked me questions (sometimes with concerns about my mental health) about why I have tentatively come to believe in what is being called ‘radical non-duality’. So I thought I would try to answer them, for the record. Here’s the basic message of radical non-duality:

There is no you. The sense of a separate person with free will and choice inhabiting a body is an illusion, an evolutionary misstep, a psychosomatic misunderstanding that seemingly arises in creatures with large brains. The brain and body have no need of a ‘self’ in order for the apparent human they are seemingly a part of to function perfectly well. Since there is no you, there is nothing you can do or learn or become to dispel or see through this illusion. It’s hopeless.

Nothing is real. Nothing is separate. There is no thing. There is only this (or nothing, or everything, or whatever word you want to use), appearing as things and actions. These appearances are not illusions like the self, and they’re not real, or unreal; they are just appearances. Inexplicably. For no reason or purpose.

Q1: How is ‘radical’ non-duality different from other spiritual traditions of non-duality that date back millennia?

It is a completely different message, and it is not at all ‘spiritual’. It is ‘radical’ in the sense that it asserts simply and categorically that there is ‘not two’ — nothing separate, no thing, no one, no time, no space, just nothing appearing as everything. And since there is no one and no thing and no time, there is no ‘path’ to realize this, and no advice on what to do or how to live to achieve anything, or any kind of self-improvement. All spiritual and traditional non-duality messages offer a path or advice for ‘you’ to follow, when the essence of non-duality is that there is nothing separate and hence no ‘you’.

Q2: How can there be ‘no one’ and ‘no thing’ when it’s obvious that we’re real and so is everything we see — we can see it, touch it, move around it, use it?

Everything is just an appearance, neither real nor unreal. It’s kind of like (but this is only a metaphor) how a movie on a screen is just an appearance — the people and events it depicts aren’t really there or happening when you watch it, though you might get so engrossed in the movie that your whole body will react as if what is being depicted is actually happening, and you may even ‘forget’ it’s just an appearance. Quantum science suggests that time and space are likewise just inventions, ideas, the mind’s way of making sense of what our senses ‘report’.

As for there being ‘no one’, neuroscience has been unable to identify any part of your brain whose activity equates to what we think of as the self, or to anything the self seemingly does. In fact there’s evidence that what we think of as the self’s decisions are merely after-the-fact rationalizations of what the body had already begun to do.

Q3: If the self is so useless and even traumatizing, why and how would it have evolved in humans? Why would the mind have invented the self, and the concepts of time and space, and come to believe them to be absolutely real, if they are not — if they are just dangerous distractions?

It’s possible the invented self is a spandrel — an accidental consequence of a brain that got large enough to be able to construct an imaginary sense of self and separation. Nature is always trying things out. Such constructions, after all, may turn out to be evolutionarily advantageous. As it turned out, however, the invention of the self confers no survival advantage and has a number of disadvantages (like capacity for trauma). In that sense it might be like the appendix — a well-intentioned nuisance that evolved but which humans would be better off without. Perhaps the reason they haven’t disappeared yet is the same reason our toes and appendices haven’t disappeared — they haven’t been around long enough yet for our genes to evolve to eliminate them.

Q4: If the self is so useless and dangerous, how have humans with selves survived so long?

Look around. There’s plenty of evidence that we won’t survive much longer. We did fine for a million years before the sense of self seems to have emerged in our species. Now, despite all the competitive advantages having a large brain would seem to confer, we deemed destined for collapse and perhaps even extinction.

Q5: But how could humans function if there was no self in control of what we do?

The same way animals do. Everything that animals (including us) do is the result of our biological and cultural conditioning given the complex circumstances of every moment. This conditioning has evolved successfully in life forms over billions of years, and conditioned creatures have no need of a ‘conscious’ mind or self to thrive. So why would we?

Q6: Aha! There’s a contradiction in that answer. How can you say something has evolved over billions of years when you also insist there is no time (and, for that matter, ‘no thing’ to evolve)?

Everything that happens, including evolution, and every ‘thing’, is an appearance. These appearances, a bit like our dreams (again, this is a metaphor), seem to follow patterns. When we (and science) attempt to make sense of things, we look for patterns, and we create models and maps that seem to represent reality. But we do have a habit of mistaking the map for the territory! Evolution is just a story, an attempt to find patterns. And every ‘I’ is likewise just a story, made up by our large and complex brains to try to make sense of things and perhaps to try to provide a locus for acting on what it makes sense of. Other creatures simply don’t have the brain power to concoct such a fiction — nor do they need one.

Q7. Why do you believe all this? You can’t prove it, and it’s completely useless — it doesn’t help you in any way. What’s its appeal?

Two reasons I am inclined to believe it. First, there are people (some of them listed on my right sidebar, if you want to check them out) who report not having a self, and not needing one. When this loss-of-self seems to happen, they say, it’s obvious that there is no thing and no one real, just appearances. They say it’s obvious, unarguable, that ‘nothing’ just appears as ‘everything’, for no reason. And secondly, there have been glimpses ‘here’ when it was absolutely obvious this was the case — when ‘I’ disappeared and everything continued to appear exactly as it did before, but with no ‘one’, no ‘me’ witnessing it. And it was clear that this appearance of everything has no substance, no weight, no actual reality. It’s impossible to describe until a glimpse apparently happens and then you can no longer deny it.

The message appeals because it resonates with something intuitive that I think we sometimes all feel or suspect. It also makes sense intellectually — it’s an irreducible ‘theory of everything’ with no inconsistencies or missing explanations to figure out. And it even appeals emotionally — I keep thinking it never made sense that life on earth would evolve to be so hard, so full of suffering and destruction, and if this message is correct, life is instead perfect and simple and easy. And even better — it’s only an appearance.

Q8. So who are ‘they’ — these seemingly-real people saying that there is no one? And if it wasn’t you who had these ‘glimpses’ you refer to, who had them?

They are just, apparently, ordinary people. They are not coordinated. They are not exceptional in intelligence, scientific knowledge, brain wave patterns, use of drugs, or in any other way. They are not trying to make money from this, or convince anyone of anything, or suggest any kind of ‘path’ or process to see it. They are just describing what is ‘seen’, what is obvious, ‘there’, when there is ‘no longer’ any self. In fact they assert there is nothing anyone can do; this apparent falling away of the illusory self just happens. Or it doesn’t. So they aren’t selling anything; they have nothing to sell. They say there is no one ‘there’, in their apparent bodies, and no need of anyone.

Likewise, during the glimpses there was no one ‘here’, so they were not ‘my’ glimpses, merely glimpses of the truth when ‘I’ got out of the way. They were no one’s glimpses.

Q9. Sounds like a rationalization to make you feel better, by denying the reality of everything horrible going on in the world, and everything horrible that’s been done, and hence denying responsibility or any requirement to do anything to make things better. Sounds like a form of disengagement or desensitization or nihilism.

I suppose that’s possible, but I wasn’t particularly troubled by any of these things at the time I discovered and became intrigued by the message of radical non-duality. I’ve suffered from lots of depression and anxiety in my life, but learning about this new explanation of the true nature of reality came during the most joyful time of my life. And if it’s a form of escapism, it’s a pretty lousy one — it offers no escape whatsoever, no solace, and it is impossible to explain to others (despite my endless efforts to do so).

Q10. If there is no one, why do ‘you’ continue to call yourself ‘I’, and behave in ways that suggest you do see real people doing and interacting with real things?

That’s partly my conditioning, and partly the fact that our languages all evolved to allow selves to communicate among each other — for us to reassure our selves that our hallucinations about reality are real. Language has no words and no capacity to express this message precisely.

And I should also stress that I still sense an ‘I’ here, still feel that ‘my’ actions have consequences and make a difference. My self has not fallen away (to my endless annoyance). It’s similar (again, only metaphorically) to the fact that I still see the sun revolving around the earth, and even refer to things like ‘sunsets’, even though I know that’s not what is really happening. There’s a huge cognitive dissonance between my intellectual and intuitive acceptance of this message, and my conditioning that suggests a very different reality and way of behaving. But the message of radical non-duality is that nothing matters, so even though it offers only cold comfort, the cognitive dissonance it produces is actually OK. Or so my conditioning has led me to believe!

Q11. This still seems riddled with logical inconsistencies. Look in the mirror. Is there a human being there, or not? A body, or not? Is it doing things, and aging, or not? Will it die, or not?

Hmm. Yes, none of this can be explained logically, even though recent science intriguingly hints at its truth. Logic is the language of selves. There is an apparent human being, an apparent body, and apparently things are being done and bodies are apparently aging. But there is no ‘real’ human or body or mirror — just the appearance of ‘being’ and ‘bodying’ and ‘mirroring’. And ‘things being done’ and ‘aging’. These are gerundive (not really either noun or verb) terms and they’re the best that language can offer to explain that there is no one and no thing and nothing happening, not really — just appearances. And appearances are not things and not actions — they are just nothing appearing as everything, for no reason. All there is, is that.

Q12: So there is no birth, no death, and no life either? When you die, what actually happens?

Nothing. There is no time in which any of these things can actually happen. There is apparently being born, dying and living, but these are just appearances. This is already everything, complete. There is no process, no causality, no trajectory. That’s just the brain’s patterning to try to make sense of everything. Death is perhaps the self’s worst invention, other than maybe the invention of its self. The self fears the body’s apparent dying because it suggests the end of the self, and to the self that’s unbearable, terrifying. When the self seemingly ‘falls away’, the illusion ends, and what’s left is just nothing appearing as everything, in wondrous, awe-inspiring ways. With no ‘ownership’ of anything. There can still be apparent emotions and feelings and thoughts, like fear and pain and imagining death, but these are just appearances, too, not belonging to any ‘one’. A body’s apparent dying, or being born, is just another appearance. Of no consequence, for no reason.

Q13: So when this body walks into a wall and gets stopped, what is doing the stopping and what is being stopped?

Nothing. What the self conceives of as a body walking into a wall and being stopped, is actually just nothing appearing as bodying, walking, walling, and being stopped. Back to the movie metaphor or the dream metaphor or the story metaphor: In a movie or dream or story, you would expect an apparent body to be apparently stopped by an apparent wall. That’s the pattern you’ve always observed. But there’s no ‘real’ body or wall or being stopped in a movie or dream or story. There doesn’t have to be. The being stopped is just a story your brain makes up to make sense of what ‘you’ perceive to be actually happening. But nothing is actually happening. You’re just making it up. Including making up your self as the observer of the story.

Q14: That’s just sophistry. You haven’t answered the question. I could make up a story that the universe is a hologram created by an extraterrestrial intelligence, that we’re caught inside. It’s equally plausible and equally absurd.

If by ‘sophistry’ and if by ‘absurd’ you mean it doesn’t really make sense, you’re right — not by the logic of language and selves. But the hologram idea is staggeringly complex, and rather unimaginative, drawing as it does on our limited, self-obsessed human ideas of intelligence and the universe. It’s plausible, but not very. Whereas the message of radical non-duality is extremely plausible. It explains everything, quite simply.

I’m not trying to convince you. It takes a glimpse, I think, before it can be really convincing. The glimpse plants a seed of possibility in the memory, and that and the inherent intellectual and intuitive appeal of the message was all it took to convince me. The radical non-dualists simply articulated it in a way that even my Doubting Thomas self could kind of make sense of.

Q15: So if you’re not trying to convince anyone of it, why do you prattle on about it so much?

I suppose for the same reason I prattle on about the inevitability of global collapse of our civilization in this century. It’s just really interesting. When you find something really interesting, especially when it’s contrary to popular wisdom, you tend to want to talk about it.