Photo by Steve Toombs, North Vancouver, young bobcat in the rain

I can see the place where I came from

I can hear those sounds right now

I can find the paths I used to run

And believe I still know how

Time keeps moving faster and faster

I’m not losing track

I’m afraid that something’s forgotten

So I keep looking back

I shake my head, clear my vision,

Keep those scenes at bay,

Feel the way I used to feel

Slip further and further away

— Cheryl Wheeler

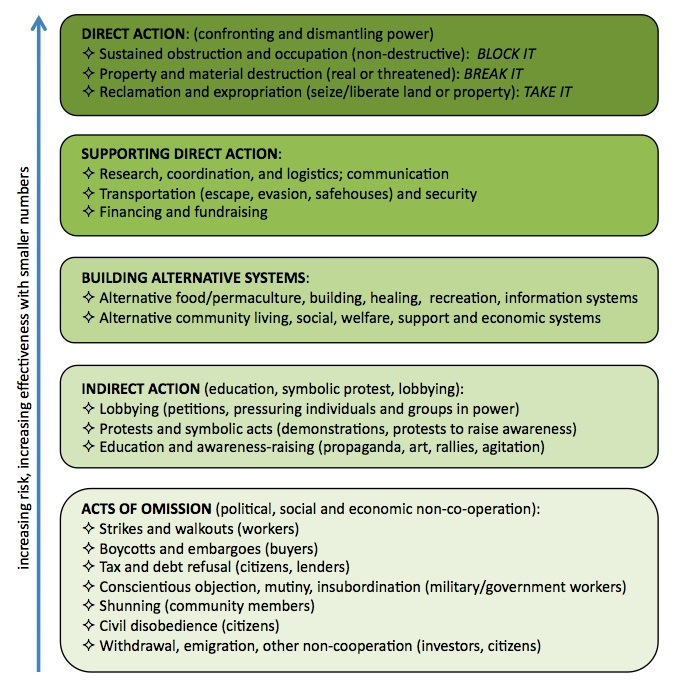

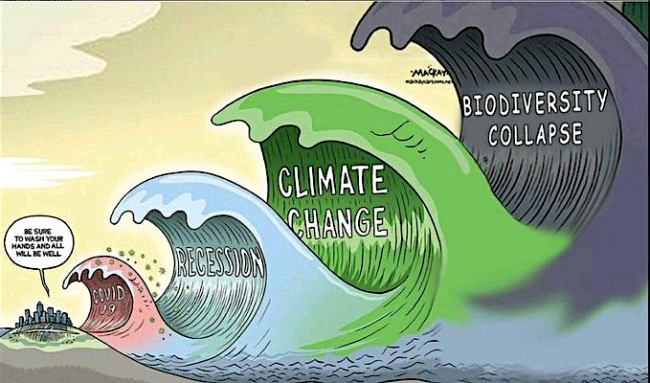

COLLAPSE WATCH

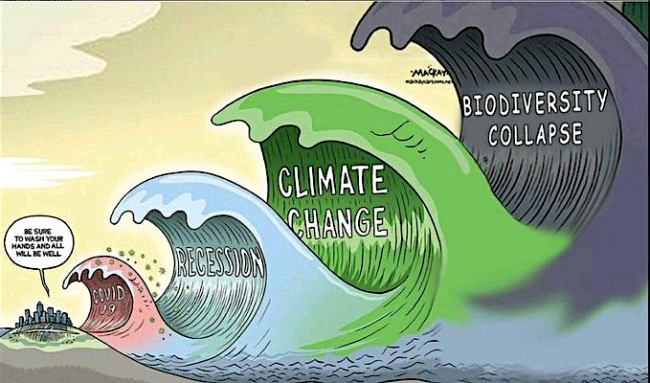

Cartoon by Graham MacKay; thanks to David Svarrer for the link. The fifth wave at the right end is, of course, civilization’s collapse. Text at left says “Be sure to wash your hands and all will be well.”

Five ways to deny collapse: Utah environmentalist Jim Catano outlines the five stages of denial that precede recognizing that civilizational collapse in this century is now inevitable. He interviews four people who have accepted that reality, including Guy McPherson and Michael Dowd, who sent me this link.

The stock market is a ticker of doom: Indi Samarajiva describes how our current multifaceted crises reflect a state of ongoing collapse, and reminds us that, in past collapses, no one recognized it or called it ‘collapse’ until after it had ended, in retrospect.

All growth is based on increasing energy consumption: Tim Watkins explains how our economy is founded on ever-increasing low-cost energy use and low-interest debt, and how the current collapse of EROEI (energy return on energy invested) belies its continuance.

The empty sea: A new Club of Rome report describes the ongoing collapse of ocean life and what that portends for our future.

When collapsniks become conspiracy theorists: Facing the cognitive dissonance between the denialist messages of the press, economists and politicians on one hand, and the increasingly obvious realities of climate, economic and ecological collapse on the other, it’s not surprising that many of us have become skeptical of what we read. What’s tragic is that this cynicism, combined with a lack of appreciation of scientific knowledge, has led a number of once highly credible collapsnik writers, including Ilargi at The Automatic Earth, Dmitry Orlov, and now permaculture pioneer David Holmgren, to become CoVid-19 skeptics or to embrace other ill-founded conspiracy theories. This is a great tragedy, because it leads otherwise sensible followers off the cliff of anti-science paranoia and misinformation, and in so doing undermines the entire field of research and study of civilizational collapse, and energizes denialists. It’s almost too depressing to write about. Thanks to Paul Heft for the link.

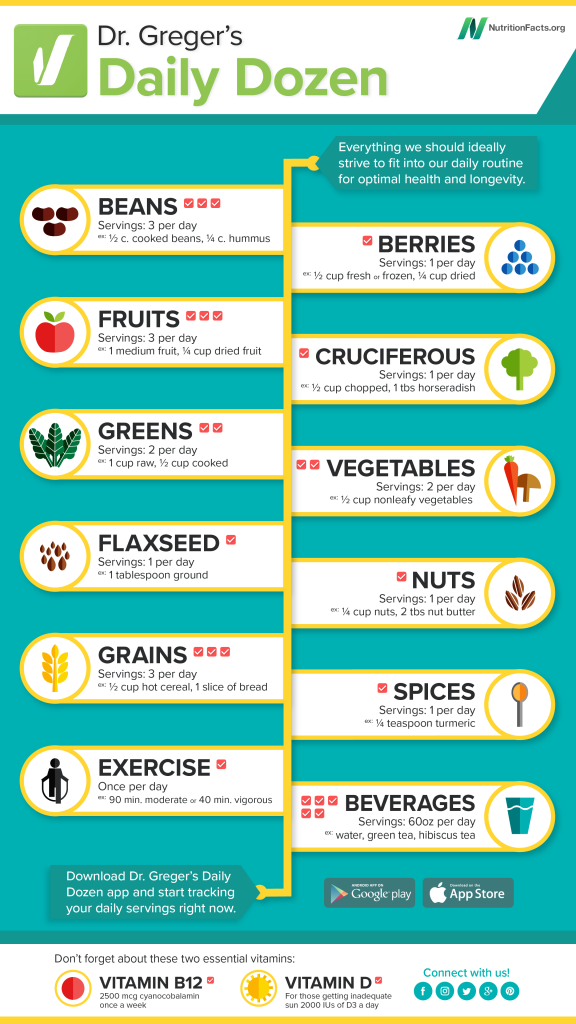

LIVING BETTER

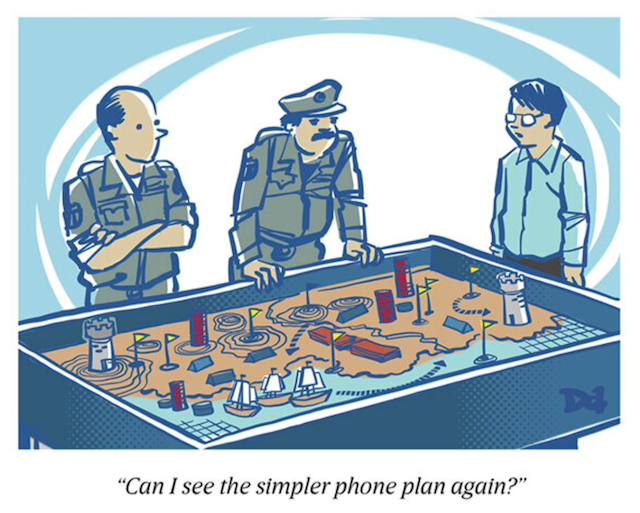

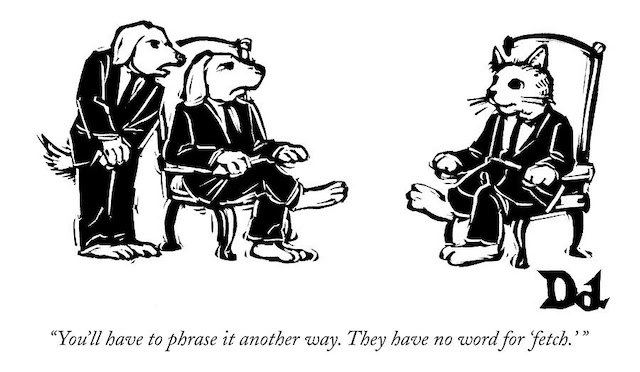

Cartoon by Drew Dernavich from his website

Putting public health first: Atul Gawande explains why Costa Ricans live longer healthier lives than Americans despite spending a tenth as much per capita on health care, because of how that money is spent.

How China eliminated malaria: From 30 million cases a year to zero, largely because of the dogged determination and brilliance of an unknown, under-acknowledged woman epidemiologist named Tu Youyou. Thanks to Kavana* for the link.

POLITICS AND ECONOMICS AS USUAL

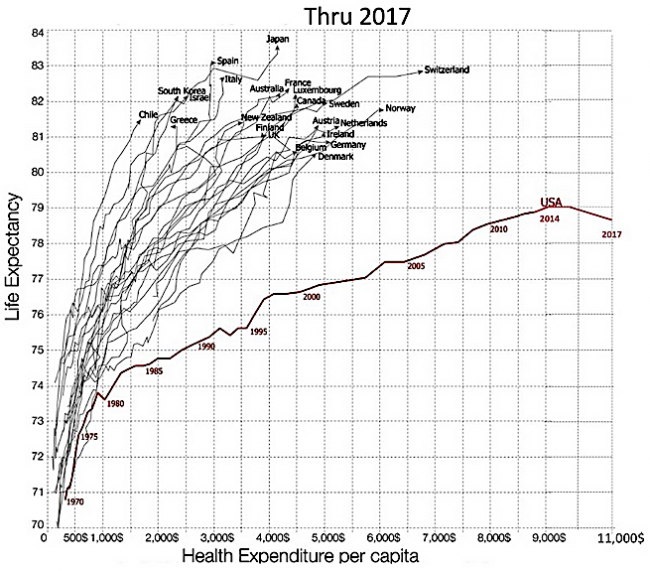

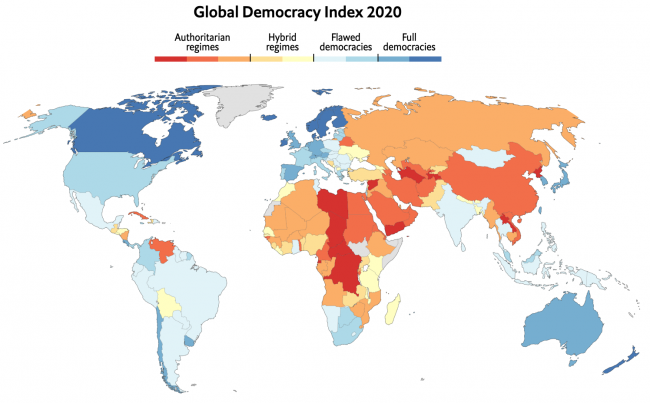

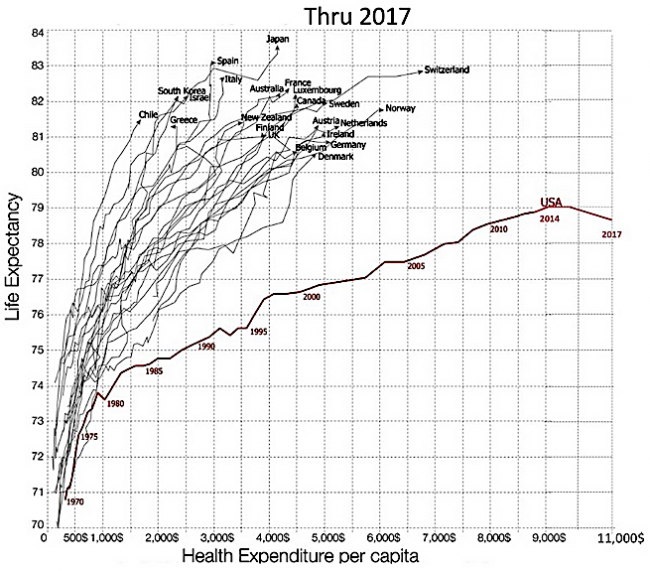

chart by Eric Topol, via Leo Beletsky

A terminal case of capitalism: Indi uses the chart above to explain how unregulated capitalism has become so dysfunctional that it now produces not just diminishing returns but negative returns.

Corpocracy, Imperialism & Propaganda: Short takes:

CoVid-19 Becomes the Pandemic (mostly) of the Unvaccinated: Short takes:

This week, I’m thinking about how little we actually understand the broad non-vaccinating population. Yes, for sure, there are some strong ideologues among them. But I’m also pretty sure there is a whole range of reasons people have found themselves unvaccinated at this point in the United States ranging from mistrust to misinformation to fear to identity to a mix of everything. That is why I think most people will go along with mandates.

I suspect the actual quitting the job because of vaccine mandates will be less than the [recent WaPo] poll indicates. The unvaccinated include many people who were just hesitant or scared rather than forceful ideologues, but when asked, people like to sound like they know what they’re doing.

I know the social media/mass media examples tend to highlight committed, outspoken anti-vaxxers but this is where a real ethnography/reporting with better sampling would help. When looking at reporting/self-narratives, I see a lot of “I was scared, kinda waited, kinda got stuck.”

Just today, I saw a tiktok from someone who, tragically, died from COVID. She says she was scared, worried vaccine wasn’t yet FDA approved, and wanted to do it later, together with her family. She needed a nudge, a push and hand-holding. A mandate could have saved life her life.

But I’m also frustrated as a researcher. I want to go talk to people, read more systematic research and try to better understand the dynamics and the proportions in the population. The pandemic has distorted our understanding of people, too: many of our examples come from social media which tends to highlight extreme and non-representative cases. It’s not that they are not real, but they are not representative, and they are especially flattened.

On pandemic news: not much new to say. I think this will rage on in the United States till more people get vaccinated or infected (but I suspect this is not a lot of time). I think there is a good case for immunocompromised, elderly, high-risk and J&J recipients to get a booster, but still not seeing the data that justifies it for healthy and immunocompetent people—especially given the still ongoing global shortage.

Inequality and Caste-ism: Short takes:

FUN AND INSPIRATION

Cartoon by Drew Dernavich in the New Yorker

The viruses that shouldn’t exist: We’ve only just discovered giruses (= giant viruses), a new form of life (or perhaps non-life) with a staggeringly complex ecosystem, most of which was also just newly discovered. We thought they were some kind of bacteria, but they’re not. They’re something else again. We’re basically clueless about what they’re for, but they’re everywhere.

Caitlin Johnstone channels Tony Parsons: Caitlin can usually be found railing, brilliantly and persuasively, against war-mongers, powerful psychopaths, and dumbed-down media, but here she perfectly articulates the core message of radical non-duality. What I can’t fathom is how she can reconcile this message with cajoling her readers to wake themselves up from their ignorance and passivity. If there is no “one” there is no “one” that can do anything. I love reading her work, but she makes my brain hurt.

Scientific tangents: A podcast developed by the vlog brothers, on fascinating aspects of everyday science. Silly, harmless fun. Like, did you know bee pheromones are being used to repel elephants from nearby farmlands? Or that Bill Gates has a huge campaign to reinvent the toilet?

First there is a mountain: Ever wondered what that mountain is that you can see from your house, your favourite campsite, or from another mountain you’ve just climbed? Now there are some fun online tools you can use, together, to solve the mystery:

- First, enter your coordinates into this site, PeakVisor. Or just move around the map in the upper left until it’s pointing where you are. Once it’s mapped the mountains, use the black and white bar to set your elevation. Then just wait for it to show you the entire 360º skyline from that location.

- To confirm your identification, enter the mountain’s name in the quick search bar in this site, Peakbagger. Copy the mountain’s precise coordinates in the upper left.

- Now, paste those coordinates in the “Coordinates B” box in this site, SunEarthTools. Enter your coordinates in the “Coordinates” box, and then click “Calculate distance and bearing”. It will show you a map, and the distance and bearing should make sense from what you are seeing. Or, alternatively, if you see a mountain that PeakVisor doesn’t identify, estimate its bearing from other mountains you can identify, and enter that bearing and the distance of the farthest mountain you can identify, and click “Calculate destination point B”. It’ll probably show you your mountain at point B on the map, or somewhere along the intermediate line.

- And of course you can use Google Maps/Earth’s 3D features to do the same, though it takes some practice to use all the settings. Once you’ve got the mountain showing on your map, right click and copy its coordinates, and paste them onto another Google Maps tab to identify the mountain. Or right click and then click “What’s here?”

Headline from the Beaverton: Toronto police leave homeless encampment in peace after residents say they’re just a 24-hour anti-mask protest.

THOUGHTS OF THE MONTH

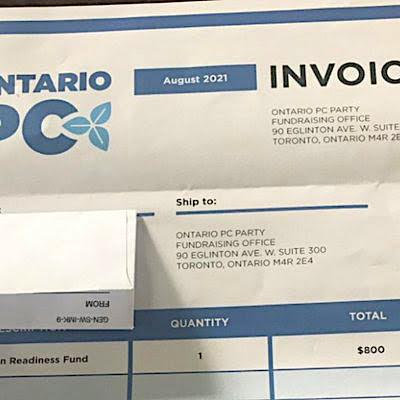

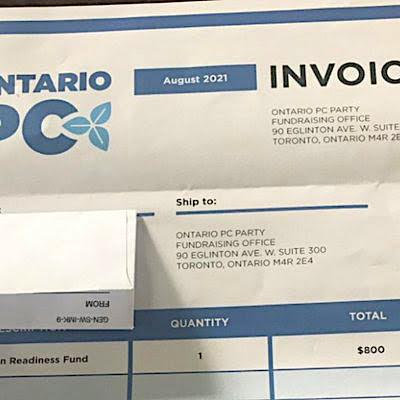

This is how Conservatives in North America fundraise. Canadians will find out Monday how well the strategy works.

From Richard Heinberg’s Museletter #342 in response to the question: Do electric, biofuel, and hydrogen powered vehicles make it somewhat more difficult to wean ourselves away from fossil fuel power?

The one thing we could do within the transport sector to ease and speed the transition would be to reduce transportation in certain modes, particularly air transport. Some vehicles are practical to electrify (bicycles, cars), while others aren’t (planes, ships, big trucks). Biofuels are ecologically a dead end, and hydrogen is problematic because it leaks so readily, and because producing it is energy inefficient. Synthetic fuels made with hydrogen solve the leakage problem, but are even more inefficient. So: there are alternatives, all of which work in the laboratory, but each suffers from some serious practical drawback if scaled up. That’s why we need to reduce transport and re-localize our economies as much as possible. As we do so, we should prioritize public transit and bicycles over automobiles of any kind, because bikes and well-designed public transit systems use much less energy and materials than cars—even electric cars.

From Caitlin Johnstone, from “Nothing to Celebrate”:

This [withdrawal from Afghanistan] is not something that Biden should be applauded for. Nobody deserves praise or credit for ending a twenty-year disaster, especially one they helped start. Nobody applauds the mass shooter for finally setting down the rifle and surrendering…

Invade a nation, kill hundreds of thousands of its inhabitants, stay for decades, accomplish nothing besides making war profiteers wealthy, drop everything and leave, then have your armed goon squad take PR photos with local infants so everyone thinks your military is awesome.

From Tim Cliss This:

This is complete vulnerability. Without the one who fears vulnerability, and works hard to assuage this fear with the illusion of invulnerability… there is neither.

The nakedness of no one to protect is total vulnerability, but no one to feel vulnerable.

Everything is nothing. Life is not a matter of life or death. Nor a question of one thing or the other. When things are no things the questions cease. This is nothing. Nothing to questions, nothing to gain, nothing to lose. Just always everything already.

This isn’t a story, but what is said or thought about this is. This is, regardless of thoughts and words about this. These words too are a story about this. Of course any thoughts or words are this too. Only this, and this alone.

From Dan Riffle, advisor to AOC: Every billionaire is a policy failure.

From Derrick Jensen, in A Language Older than Words:

What do you do, how tired do you get, when each day you struggle against an entire culture based on the normalization of trauma-inducing behaviour? There is no sanctuary.

From John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath (thanks to Caitlin Johnstone for the link):

“We’re sorry. It’s not us. It’s the monster. The bank isn’t like a man.”

“Yes, but the bank is only made of men.”

“No, you’re wrong there—quite wrong there. The bank is something else than men. It happens that every man in a bank hates what the bank does, and yet the bank does it. The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”

* Kavana is Tree Bressen‘s new name.