Thinking more about this astonishing eight word phrase, from Amy Rosenthal via John Green: Pay attention to what you pay attention to.

Over the past decade, I’ve given up thoughts of “improving” myself, what some people call doing the work of becoming a more sensitive, empathetic, complete, useful person. Perhaps it’s just laziness, or fatigue, but I think my giving up is more likely because I’ve abandoned the belief we have free will, given up thinking we have any choice over what we do or don’t do.

Instead I’m simply trying to become a little more self-aware of what’s going on inside this probably-illusory mind inside this apparent body ‘I’ bizarrely but unquestioningly presume to inhabit. Catching myself when I get reactive, defensive, triggered, self-righteous, or just plain anxious. Just noticing that, and as much as possible doing so without judgement.

Lost, scared and bewildered is kind of the essence of who ‘I’ am, so recognizing my disorientation, my fears, my bewilderment, in the moment, is a strange kind of awesome. It’s a fleeting recognition that there is no real ‘me’, and that the sense of self and separation that is essential to feeling lost and scared is an illusion, a construct, a fiction.

At one time I thought I might at least learn to choose what to pay attention to — the stuff seemingly inside, and all the stuff without. But I see now that there is no choice; what we pay attention to, or fail to pay attention to, is utterly a result of our biological and cultural conditioning, given the circumstances of the moment, and we have absolutely no control over it.

But somehow, paradoxically, it seems possible to be aware of that conditioning and the apparent actions it inevitably prompts, as if I were looking at someone else.

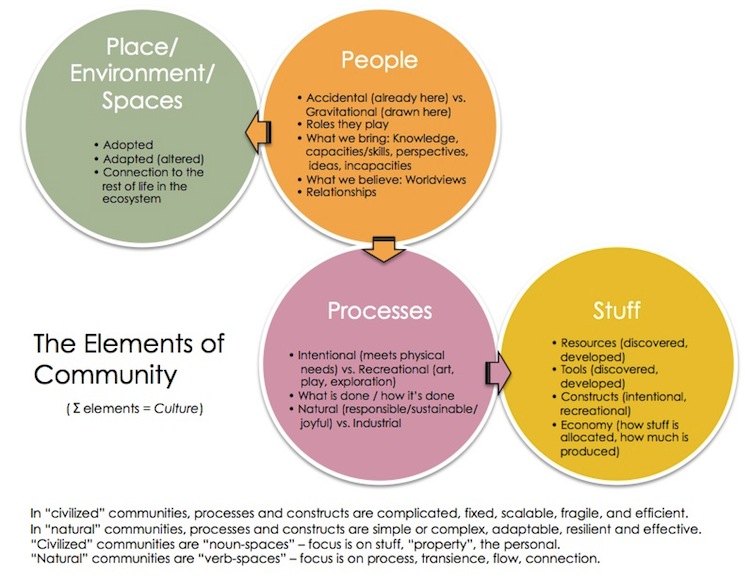

Coquitlam, my new home, the place I have recently been ‘transplanted to’, is very different from Bowen Island, my home for the previous twelve years.

I’ve moved a mere 60km from a house on a 300m hill a half-mile from my neighbour on an island of 3800 people, to an apartment 42 floors up in the middle of a city of a quarter of a million people (the so-called “TriCities”). I’ve moved from the northwest extremity of Metro Vancouver to its northeast extremity. Lots of green and mountains outside my window, still, but even on the roof I can’t see the stars anymore, even on a cloudless night. I’ve gone from five lights visible from my bedroom at night, to tens of thousands.

And it’s noisy. People yelling, honking, and gunning their engines. Car alarms, trucks beeping backing up, shunting trains, squeaking brakes, sirens, banging garbage trucks, unidentified industrial noises, and the constant hum of traffic.

I noticed myself paying attention to the brightness, the urban sprawl of subdivisions and parking lots, and the noise. And then to my surprise, I stopped paying attention.

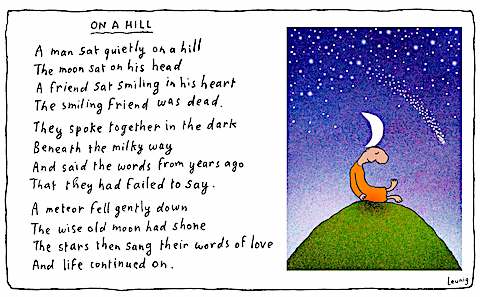

Instead, I’m sitting here on a late summer night, having watched the sunset and the falling dark from the roof. I’m sipping on a mug of tea, looking at the astonishing, garish, awful, wonderful display of lights you can see in the photo above. I’m listening to VOCES8 on headphones, singing the music of Ólafur Arnalds , Eric Whitacre and Rachmaninoff.

I noticed that I didn’t put the headphones on to drown out the Friday night city noise. In fact I noticed that I wasn’t paying attention to the noise at all. I was paying attention to the lights, and the music that I put on just seemed the right accompaniment to the new, astonishing light show outside the window.

It has been a long time since I’ve felt so much at peace, and I’ve found it here amidst all the noise. Just because of what I’m paying attention to, and what I’m not paying attention to.

I’m noticing other things that never caught my attention before, too. I’m noticing the different ways the wildly diverse cultures represented here in Coquitlam (half the population are visible minorities) look at me (and at others), or don’t, and the different ways they express what comes across as politeness but is probably more nuanced than that. Still figuring all that out — more attention required.

I’m noticing the brightness, the features, and the angle at which the moon waxes and wanes. I’m noticing that you can infer most of someone’s facial expression, even hidden behind a mask, from the expression of their eyes, eyebrows and the line of their jaw. I’m noticing the change in the ‘tone’, the weight, and the smell of the air as I pass from areas that are open, to those sheltered by greenery, or near streams and rivers.

Part of the reason I’m noticing — paying attention to — new things, is that everything is so different here from how it was on Bowen Island. I think that is one of the important virtues of travel to see different ecosystems and different cultures — we get inured to things after a while, and no longer notice them, but when we’re suddenly surrounded by things we are not used to, we have no choice but to pay attention. It’s like suddenly regaining binary vision after having to make do with one eye for a while.

I think one the main reasons I’m paying attention to more and different things is that I’m no longer paying attention to other, unimportant things, or at least not giving them as much attention. Most significantly, I’m not paying as much attention to my thoughts as I used to, which shifts my focus from the internal to the external. I’m not sure why that is, but it seems to be healthy.

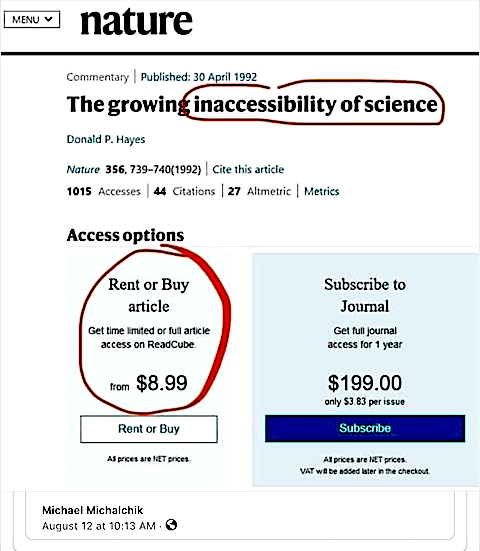

I’ve also stopped paying attention to the endless distraction of social media and the news scroll. It was a total, addictive, time suck. Facebook and Twitter still send me daily email notifications of posts by people I apparently once ‘followed’, carefully curated to draw me in. Of course they require me to go to their sites to see more than the ‘teaser’ the email includes, so they can then bombard me with more sensational posts. But now I delete the teasers without looking at them.

The NYT has now done me a favour by doubling down on their paywall, so that even with incognito mode I can’t read their articles unless I time the switch to ‘reader mode’ just right. Very few articles are worth that hassle. So I scan the ‘top 10’ headlines from the websites of the Tyee, CBC, NPR, Atlantic, Guardian, Al Jazeera, and the NYT, on my Protopage.com newsreader page, once a day, and on an average day will visit just one link for more details — usually an analysis from a favourite writer or a rare article that is actually actionable. Once a month I scan what’s new from about 30 blogs, vlogs and websites that have consistently offered useful and insightful reporting, research and perspectives, usually just before I post my “links of the month”. That’s all the news I need, I think, to stay current, informed, and sane. Works out to about 20 minutes a day.

That frees up a lot of time for paying attention to things that are more fun, more immediate, healthier, and more useful to pay attention to — with all my senses. And, a little bit more each day, that’s happening without the over-thinking, judgement, “sense-making”, and “what does that mean?” interpretation that has characterized my attention most of my life. It’s enough it seems just to notice, just to pay attention. Most of the time, trying to make sense of everything just gets in the way of really seeing, hearing, sensing what is happening.

Can paying attention to what we pay attention to, actually change what we pay attention to, or how attentive we are, or how much we appreciate and enjoy paying attention? I don’t know — I’m too new at this, and besides, I have a sense it doesn’t matter anyway. Even as my self-awareness seems to grow, and my attentiveness shifts, I am even more aware that I have no choice in any of it. It’s just what’s happening, apparently, here, now, on this terrace in the sky in Coquitlam, on the 240th day of the 21st year of civilization’s final century.

O

O