image by greentumble.com

In his articles and books, Richard Manning describes high-maintenance monoculture, which has prevailed in much of the world since the early days of civilization, as “catastrophic agriculture”. He uses that term not because of its impact on the environment, but because of what it requires humans to do to maintain it — precipitate an endless series of simulated, unnatural ecological catastrophes (in the form of poisoning crops with toxins to kill pests and weeds, addition of unnatural fertilizers, elimination of complementary crops in favour of a single crop, and using unnatural amounts of water).

The result is a very fragile system, dependent both on a high degree of weather stability and on constant human (and now machine) interventions, to “force” the soil and the monoculture crops to produce a maximal amount of one specialized type of human (and human-consumed animal) food. Most gardeners today practice catastrophic agriculture, because they never learned any other way.

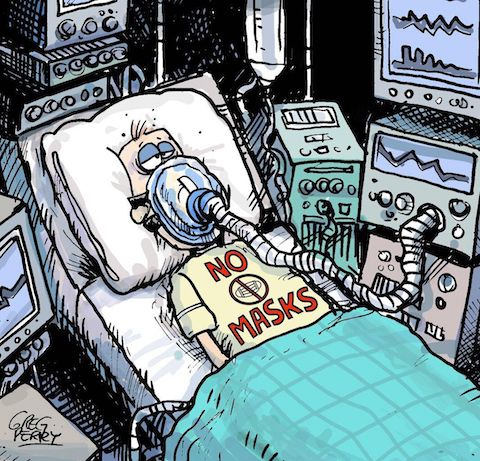

In similar terms, our current untrammelled hyper-capitalist economy might well be described as “catastrophic capitalism”. Artificial interventions in markets (like the 2008 bailouts, the vast and constant corporate subsidies of many industries, notably petrochemicals and the military, and the deliberate suppression of interest rates to encourage endless and reckless borrowing while punishing savers and those on fixed incomes) are now absolutely essential to “market growth” and hence global industrial capitalism’s continuance.

The result, again, is a desperately fragile system, with ghastly amounts of waste and inequality, leaving the system and its citizens utterly dependent on these artificial interventions, and requiring blind citizen/consumer obedience to enable them to continue, despite their destructiveness, unfairness and the massive suffering they cause.

This is what a culture (and a Ponzi scheme) does in its death throes. It desperately tries to perpetuate the existing system even when the costs vastly outweigh the advantages. The whole system is deemed “too big to fail” because knowledge of less dysfunctional systems has been lost and forgotten. History is replete with stories of the collapse of civilizations and societies that went “all in” on one way of doing things, even when that way of doing things was no longer viable, and even when it was utterly dysfunctional and self-destructive.

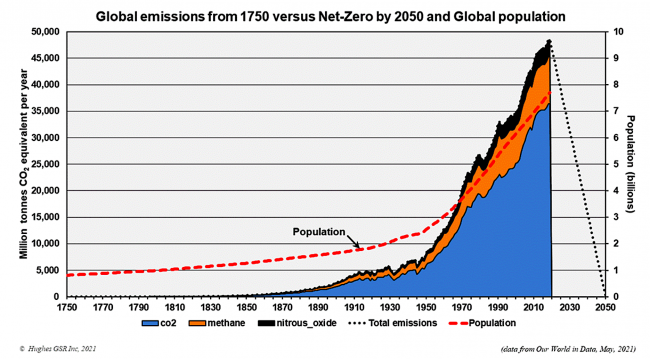

When systems of catastrophic agriculture begin to collapse, due to climate change, exhaustion of soils and water, or epidemic disease, the attempt to perpetuate such systems anyway might more accurately be called “Extinction Agriculture”. The Irish potato famine is one extreme example of what can happen. Complete dependence on a fragile and unsustainable system, with no viable replacement system available, will inevitably lead to the extinction of critical elements of the system and, as it collapses, the extinction of those dependent on it.

Similarly, our modern, fragile, unsustainable system of catastrophic (fragile, overextended, artificially supported, and perpetuated against all reason) capitalism, has now reached the stage it might accurately be called “Extinction Capitalism”. Like our modern industrial food system, it is killing us, and our planet, and still, ludicrously, we continue to support it.

image from XR, by Vladimir Morozov/akxmedia

Extinction Capitalism is, like other self-destroying systems, the result not only of forgetting possible alternatives to the prevailing but now dysfunctional system, but also of incapacity to imagine and hence create a more viable system.

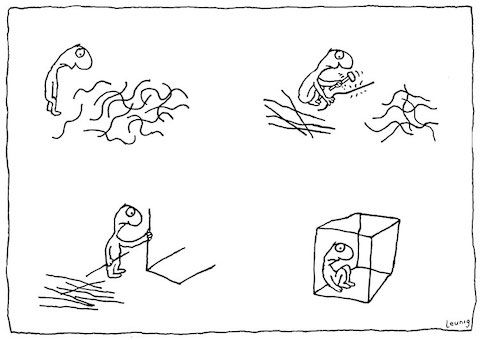

I have argued that we live in an age of immense imaginative poverty. Imagination is a capacity that must be learned and practiced. Children were once encouraged to develop that capacity, but now the toys, games and media they are exposed to actively discourage and stunt the imagination, replacing it with rigid instructions and rules, preset boundaries and options, and a bunch of tech-induced visual thrills that make them passive consumers of the culture, primed for more kits, sequels and simplistic binary plots and precluded from considering any possibilities other than those the programmers, who suffer from similar imaginative poverty, have preconceived. Everything in our modern technology-obsessed culture is formulaic, constraining, artificially thrilling and relentlessly numbing.

That is not to say we are not creative. The detritus of human productivity that now weighs down our world came about because we have a predilection to make stuff, to create. But in a world of imaginative poverty, that creativity is derivative, replicative, devoid of novelty and originality, and lacking in any appreciation of the astonishing lessons that the natural world, outside our prosthetic human one, has to offer.

So instead of new ideas and possibilities inspired by practiced, collaborative, imaginative thinking, learning from the more-than-human world, we instead have a bunch of bored billionaires competing to see which of them can make or buy his way into outer space first. And numb, equally unimaginative media passively reporting on this competition and on other ‘celebrity’ activities.

And, instead of inventors and experimenters, we have dimwits running our political and technological systems, people who have never had an imaginative thought in their entire lives. As a result we have ever-more-derivative social media that offer all of the exploitativeness and none of the potential that global connectedness and collaboration might have offered, had it been imbued with imagination rather than simply harnessed for private profit.

So Facebook is a ghastly, dysfunctional, time-wasting replicator of unoriginal material, much of it deceptive or simply wrong, essentially a clone of an earlier tool that didn’t get big enough fast enough or ruthlessly enough to control the market. We are now its product, not its customers.

Amazon is just a private monopoly that did what a properly-run and properly-funded post office could have done much better, and could have run as a public utility for everyone’s benefit — had the 1% not conspired to starve public institutions in the interest of private “enterprise”.

And Twitter is just a pathetic, useless addiction — a machine for public masturbation, the ultimate manifestation of what Neil Postman called “amusing ourselves to death”.

So this is where we are, much like many previous civilizations that grew too large and too sclerotic to continue to function, and then collapsed, mostly unmourned. Most of our civilization’s citizens have developed a common and utterly useless specialty — we have become mindless, unimaginative, overweight, malnourished, placid obeyers of authority, unthinking consumers of more and more stuff that we don’t need, can’t afford, and which is killing our planet, and capable only of doing what we’re told, because we can’t imagine doing anything else. And this tragic state has not even made us happy.

Extinction Capitalism isn’t the cause of our disease, just the instrument of our execution. We are so busy looking at the barrage of messages and sparkly colours on all the pretty, irresistible screens we are surrounded with, that we can’t see the noose, slowly lowered and tightening around our necks. And the footing on the road ahead, especially when we’re not looking, is pretty precarious.

In Part Two I’ll speculate on where I think Extinction Capitalism is taking us over the next ten rocky years.

O

O