image by Neil Howard on flickr CC-BY-NC2.0

Ontology is “a gathering of or speaking (-logy) about ‘what is, what exists’ (onto-)”. The suffix -logy has come to mean a study or science, but originally it just referred to something said (the word monologue has the same root). So an ontology is a statement about what is.

The radical non-duality “message” is, essentially, an ontology, though a very unorthodox one. It is not a theory — its messengers assert that it is absolutely true, undebatable and obvious, and that it is only our illusory selves that cannot see this truth. The message is simply this:

There is no you. The sense of a separate person with free will and choice inhabiting a body is an illusion, an evolutionary misstep, a psychosomatic misunderstanding that arises in creatures with large brains. The brain and body have no need of a ‘self’ in order for the apparent human they are seemingly a part of to function perfectly well. Since there is no you, there is nothing you can do or learn or become to dispel or see through this illusion. It’s hopeless.

Nothing is real. Nothing is separate. There is no thing. There is only this (or everything, or whatever word you want to use), appearing as things and actions in (apparent) time and space. These appearances are not illusions like the self, and they’re not real, or unreal; they are just appearances. Inexplicably. For no reason or purpose.

That’s it. That’s the message. Everything else that radical non-dualists talk about is just an elaboration, an illumination, of the essence and consequences of this simple, hopeless message.

So we might inquire how and why this useless, annoying, suffering-causing illusory sense of separate self arose in this seemingly perfect-just-as-it-is “one-ness” appearing as everything (although if this message is true there is actually no “how” or “why” for anything).

There are possible evolutionary explanations, as I’ve described before — perhaps when large brains evolved the capacity to ‘model’ everything they perceived in order to make sense of it for survival purposes, that ‘model’ turned out to include a ‘self’, and when that ‘self’ was conjured up it began to use the brain’s power to perceive of itself (and everything else) as real and separate. There is growing evidence (from physics) that time and space aren’t ‘real’ (in the sense of being scientifically objectively verifiable) either — they’re just mental constructs used by the brain to organize and make sense of sensory perceptions. So why couldn’t the same be true of the self, itself?

If that’s true, then it implies that we, the supposedly super-intelligent, knowledgeable and super-conscious species, are actually the only species that cannot see through the illusion of its self, ie the only species that can’t see everything as it truly is — as a wondrous appearance of everything out of nothing, outside of space and time, without meaning or purpose or intention or anything separate.

If the message of radical non-duality is true (and over the last several years I’ve come to believe it is), then it is the most profound, and the most humbling, discovery in the history of our species. It means that our species is the only one hopelessly afflicted and debilitated by a hallucination that causes its victims untold suffering for no reason, and renders us uniquely unable to see what actually is. And who are its victims? Not the naked bipedal creatures ‘we’ presume to inhabit. These creatures are just appearances out of nothing, so they can’t be victims.

The victims of our selves’ psychosomatic misunderstanding are our selves. If this sounds recursive, it is. It would appear that our brains conjured up an illusory, imagined self so convincingly that it made that illusion ‘self-conscious’ and capable of believing itself real.

How can something invented become ‘self-conscious’? Well, what does it mean to be ‘self-conscious’? It means to believe itself to be real and separate and aware of something other than itself. AI fans are intrigued with the idea that robots could eventually do just that.

But if nothing is real, how could a self come to believe itself to be real? Because that’s what it perceives, how its conceptions makes sense of its perceptions. How can something that isn’t real have perceptions and conceptions? Anything is possible. Why not? If the sleeping brain can have a dream or nightmare that seems astonishingly real (perhaps enough to cause the body of the dreamer a heart attack), when it isn’t real at all, why should it be impossible that the (unreal) self can dream it is real and its experiences are real, when it is just an illusion, something conjured up by a pattern-making brain?

Let’s take a step back. The radical non-dual ontology says there are no ‘real’ creatures, brains, dreamers, heart attacks, lives, deaths, places, times, or things of any kind; there are only appearances of these things. What does it mean for something to be an appearance? (This is not the same as something being an illusion — a psychosomatic misunderstanding).

This is where the self’s understanding falters, and runs into the constraints of self-invented languages. The (illusory) self, which perceives itself to live in a dualistic world, where everything is either real (ie fits within its conceptions of what is real) or unreal (ie fits within its conceptions of what can be imagined) cannot conceive of or imagine what an ‘appearance’ is. An appearance is neither real nor unreal. It is not a conception, it is not a perception, it is not something that is or can be imagined, conceived or perceived by the self. How can it then possibly be true? Because it appears that when the self drops away (and it is seen that it never actually was) everything that is, is suddenly, wondrously, seen, as an appearance — by no one.

How do we know? We don’t — but (apparent) messengers of the radical non-duality ontology who claim ‘they’ don’t exist and do not ‘any longer’ have selves say this truth is now seen. Why should we believe them? Because their ontology is air-tight; it has no flaws, no loose ends, no ‘dark matter’ still unexplained, no contradictory arguments, no inconsistencies; no one could invent and ‘argue’ an ontology this brilliantly, and continue to do so for decades, as Tony Parsons has done for example.

And as perplexing as this ontology is, to some extent it is intuitive, even obvious to everyone. Whenever there is a ‘glimpse‘ it is seen to be true. When it’s accepted it is actually profoundly satisfying, since everything suddenly makes sense, including all the unhappiness and frustration the self feels, hopelessly and needlessly, life-long.

But it makes no sense to the self. It seems utterly preposterous. And even when science is able to eliminate all other possible ontologies (and I’d guess that will happen by the end of this century, if our civilization lasts that long), it probably won’t be accepted by most people as other than a useless scientific curiosity, like black holes.

It’s been suggested that belief in radical non-duality is just another dogmatic ‘self-denying’ religion — something that someone desperate enough for an easy answer to life’s apparent suffering will glom on to as a last resort, a coping mechanism during their ‘dark night of the soul‘. This is probably the hardest argument to address, since radical non-duality does partly meet the broader definitions of religion as a “system of faith and worship” or as a “system of beliefs, symbols and practices that addresses the nature of existence, and … is lived as if it both takes in and spiritually transcends socially-grounded ontologies of time, space, embodiment and knowing.”

But I don’t think it qualifies as a religion because:

- it has nothing to do with spirituality or belief in a higher power or the supernatural

- it has no object of worship (not even Gaia)

- it is built on skepticism about other ontologies, rather than on faith (ie an unsupported or unsupportable belief) in an ontology

- rather than being in conflict with, or dealing only with areas outside of science, it seems to have considerable scientific support (in neuroscience, quantum physics, astrophysics and cosmology)

- it entails no practices and offers no pathways to or ideas about better ways to live

- it offers no solace, salvation, redemption, comfort or any of the other apparent benefits of religious belief

So, back to the sheer preposterousness of this ontology. If it’s so “obvious”, why does almost no one subscribe to it?

The history of the human species is replete with belief systems that lasted millennia because they were simply the best that available scientific and other empirical evidence could come up with. And humans want to believe, and will accept almost any belief system that isn’t obviously wrong, dangerous or useless. We have believed (and some still believe) in magical and evil spirits, in reincarnation, in a geocentric universe, in a flat earth, that the earth was created by a superhuman in six days, that babies and non-humans cannot feel pain, that diseases are caused by humours or miasmas and can be cured by faith-healers, etc.

We generally believe (a) what we’re conditioned by parents, peers and other trusted people to believe, (b) what we learn that isn’t inconsistent with what we already believe, and (c) what we want to believe (because it’s easy, safe, or for other personal reasons). It is likely that billions of people still don’t believe in evolution. Many believe in outmoded ideas like the “big bang” or string theory simply because others have persuaded them that these theories seem to be consistent with scientific knowledge, and no better theory has been presented and explained to them.

So the fact that there is not even a small consensus on the validity of the ontology of radical non-duality is probably not surprising. It is very new (though in some ways very ancient — there is after all no such thing as “progress” of ideas and belief systems). It flies in the face of centuries of scientific thought. It is hopeless (there is no path to realize its veracity), useless (it offers no guidance on any subject), and it creates a host of moral dilemmas (it denies the existence of purpose, meaning, free will, self-control, or responsibility). In fact the only thing that it seems to have going for it is that it’s perhaps the only ontology that explains everything and isn’t directly contradicted by very compelling evidence. It is, perhaps, the ontology of last resort.

Suppose this ontology is correct. What would happen if it became largely accepted? Nothing would change. Because if it’s correct, and selves and separation don’t exist, then acknowledging that truth isn’t going to change anything. Those whose selves have apparently fallen away seem to behave almost exactly as they did before, confirming that the self, being an illusion, doesn’t actually influence anything — the apparent character (body+behaviours) ‘left behind’ continues to do what it’s been biologically and culturally conditioned to do. What seemed to be ‘decisions’ made by selves were discovered to be merely ‘rationalizations’ for what the character was going to do anyway.

So when I wrote earlier that humans are the only species that can’t see everything as it truly is, that’s kind of unfair to the billions of apparent human bodies on the planet that, unbeknown to our ‘selves’ are not actually separate or unable to see what truly is. What “can’t see everything as it truly is” are the selves that presume to inhabit those bodies, and which are disconnected from ‘everything that is’, including our remarkably competent (without any self telling them what to do) bodies.

So there is nothing to lose, or to gain, if this ontology becomes widely accepted. What will continue to (apparently) happen is the only thing that could have happened.

Our languages are utterly ‘self-ish’. They consist primarily of nouns (things that don’t actually exist), pronouns (references to self and others, which are illusory), and adjectives (conceptual, perceptual and judgemental descriptors of these non-existent things). Every sentence, by its grammatical form, is a story fragment — a fiction. Thoughts and feelings and personal sensations and perceptions, in the absence of language, are ephemeral — they have no substance, import or reality. They can’t be ‘made sense of’ without the context of a story, ie without language.

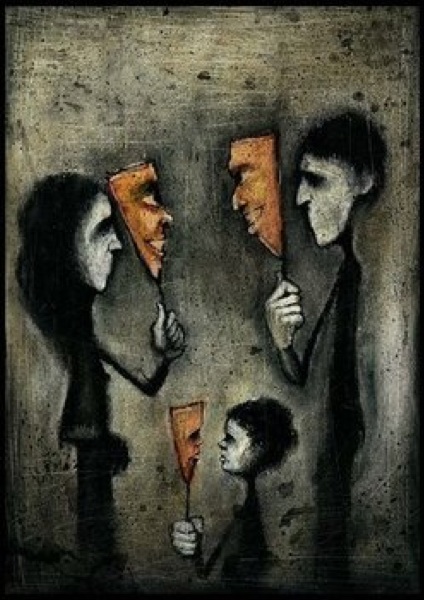

It is only when the self takes ownership of these ephemera that it ‘makes’ them real. Then, using language, the self weaves them into a story (about seemingly ‘real’ things existing and happening in ‘real’ time and space, and full of ‘real’ causality). And then these “psychosomatic misunderstandings” (as Jim Newman calls them) begin to wreak havoc on us — setting up the vicious cycle of what Eckhart Tolle calls the “egoic mind’s” often-terrible (and always invented) conceptions, perceptions, ideas, judgements, stories, expectations and beliefs, and the “pain-body’s” reactive negative emotions. Egoic mind sees loved one hugging stranger, invents a story about its meaning, and reacts with jealousy. And that jealousy then feeds more imagined aspects of the story, which fuels more reactive pain etc.

Language thus entrenches and reinforces the self’s sense of separation. Without it, could there even be a sense of self? Have humans always been afflicted with this sense of self?

There is (hotly debated) evidence that the first settlements, agriculture and abstract languages (the three hallmarks of ‘civilized’ society) all began about 10-20k ago (by contrast, human art dates back at least 100k years). These civilizations likely emerged independently in widely dispersed areas on five continents.

It is plausible that abstract language only evolved because it was needed to function in complex agricultural settlements, but it’s probably safe to assume all three hallmarks co-evolved and that all three are essential to a functioning civilization culture. There’s also some (equally-debatable) evidence that civilizations arose either (1) because exceptionally-comfortable post-ice-age climate conditions (since ~10k years ago) allowed massive increases in populations in suddenly-lush areas that had been largely lifeless when they were under mile-thick ice, or (2) because exceptionally-grim late-ice-age climate conditions (~20k years ago) forced humans to evolve civilizations in order to survive.

Whichever theory holds, it is interesting to speculate whether, prior to ‘civilization’, when we lived in relatively tiny numbers in tropical forests (and, later, as many vast forests burned due to more climate change, savannas), humans actually had selves. There is a credible argument that our first expansion (perhaps expulsion is a better word) from the once-all-providing forest to the unfamiliar and more perilous seashore enabled us to start to consume large amounts of amino-acid-rich (and plentiful) fish and seafood, which led to the major increase in the size and capacity of our brains, perhaps beyond the tipping point that would allow the idea of the ‘self’ to arise. Indeed, most early civilizations were in coastal areas.

This argument, then, would hold not only that climate change both provoked the emergence of human civilizations, and is now causing the termination of our global human civilization, but that illusory human ‘selves’ are concurrent with both stable climate and civilization culture. That would mean that pre-civilized humans were not conscious of themselves as separate and not afflicted by the illusion of selves with their commensurate, useless, body-mind trauma. It would also hold that when our global civilization culture fizzles out with the end of stable climate later this century, the (relatively small number of human) survivors millennia hence will not be afflicted with selves, and will not have civilizations, (catastrophic) agriculture, settlements or languages. Lucky them! What an amazing time that will be! But for no one, since the apparent human bodies will have no sense of being separate and apart from everything that (apparently) is.

Why wouldn’t these post-global-civ humans just reinvent language, settlement, agriculture, and civilization? Because they wouldn’t need any of these things to thrive, as humans apparently did for most of a million years before the ice ages. Even if selves emerged in certain large-brained post-civ humans, there would be no cultural conditioning to reinforce the illusion that the self was real, and hence it would be ignored, and not evolutionarily selected for.

How can any creature function without any sense of itself? When we study tiny wild creatures with minuscule brains (like silverfish or aphids), we see an amazing and clever instinct for survival, honed over millions of years to know just when and where to flee or freeze. When we study wild creatures that have no brains at all, like jellyfish, we likewise see amazing intelligence, but if there can be said to be a self in such creatures, it would have to be plural, since they have no centre, no place for a ‘self’ to reside.

When we study large-brained wild animals, like whales and elephants and ravens, we insist they must have a sense of self, and other, to explain many of their apparently clever, self-absorbed or altruistic activities. Yet none of these creatures has (to our knowledge) invented abstract language, catastrophic agricultural processes, complex settlements, or large-scale complex civilizations. Why not? Because they don’t need them. Whales have lots of the stuff of complex brains, so it’s clear they could evolve these things if it served an evolutionary purpose to do so, but it doesn’t. Does that mean they don’t have selves?

I would argue that they don’t have selves because they don’t need them, either. A self needs nurturing, conditioning, reinforcement. I would say that without abstract language it is impossible to ‘teach’ infants of any species to acknowledge and accept their selves as real. Without language there can be no stories, no sense of individuality or purpose or apart-ness — no sense of self. So even though a baby whale surely has the brain capacity to create a model of itself, even if it did so, would it take it seriously? Without language reinforcement from other whales, why would it consider the model of the self as any more than it is — a mental construct of no evident use or import?

There have been studies that indicate these complex creatures live most of their lives in a perpetual “now time”, unaware of the existence of “clock time”, of their separateness, or of anything apart. And then in moments of existential threat (eg a looming predator) they briefly enter an ‘altered state’ that causes them to fight, flight or freeze, and to use everything in their power (including their considerable wits) to protect themselves or their tribe-mates. And then it is physically ‘shaken off’ — like a bad dream — after which they return to “now time”. This makes enormous evolutionary sense.

Unfortunately, in humans, in crowded, precarious, agricultural settlements and massively overpopulated, crowded, unfathomably-complex civilized cultures, the stress that brings about this ‘altered state’ is chronic — it never goes away. So how do we cope? Enter the self, valiantly trying to make sense of this unnatural and traumatic state that you never seem to wake up from. And the self decides it is real, that everything else outside it is real (especially those threats), that it is in control (someone has to be in this awful chaos!), that it has free will and choice, and that it is responsible for the survival and well-being of the body it now presumes to inhabit. It invents language to communicate its trauma, and what might be done about it, to similarly afflicted selves, in the hope that selves working together will accomplish more than a lone self. And it never wakes up.

The tragedy of course is that this well-meaning self doesn’t actually do anything. It is the dream (or rather the nightmare, the prison it has caught itself in) it is trying to solve, to make better. Just as with every other creature, the human body knows, from a million years, a billion years of evolutionary learning stored in its DNA, just what to do. Not only does the self not do anything, it doesn’t even get in the way. It is a self-created illusion.

The question is not how we could or would function without selves, but rather how we are able to function perfectly well without selves. In part, that is the wonder of evolution — no ‘self-conscious’ self is needed (which is a good thing, because the self is pretty poor at what it does, in case you haven’t noticed).

Hidden beyond the veil of your self, that body that you’ve come to think of as yours is an amazing evolutionary ‘machine’ that doesn’t recognize or see ‘you’ at all, and it knows exactly what to do. No help from ‘you’ or ‘me’ required.

Beyond this dream-veil of the self the wondrous oneness of everything — not real or unreal, just everything appearing to happen, beyond time or space — is seen as it truly is. Not seen by a body, not seen by any one, just seen for what it, astonishingly, is. If you know (kind of) what I mean by a glimpse, you’ll understand. But you’ll still be trapped in the prison of your self.

If this makes no sense to ‘you’, it doesn’t matter. Everything will go on appearing, perfectly, wondrously, outside of ‘you’ and ‘me’, eternally and everywhere. Except when and where ‘you’ and ‘I’ are, hopelessly, looking.