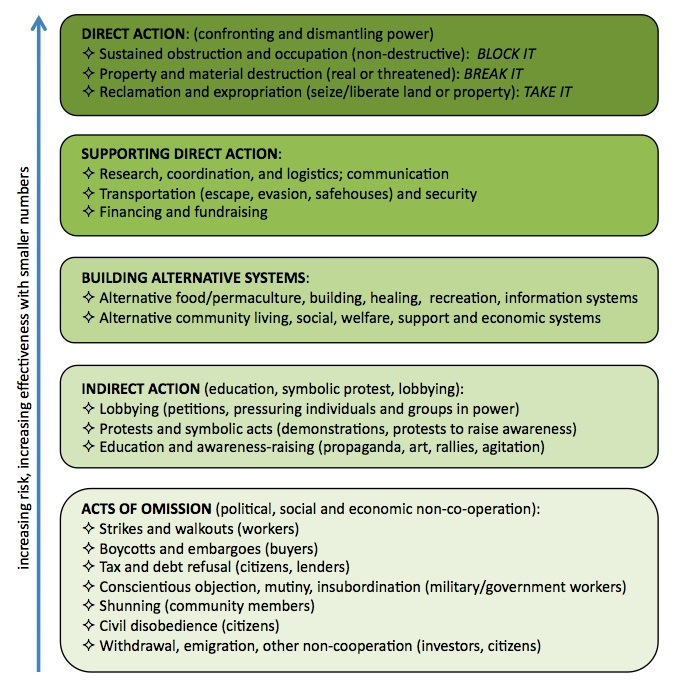

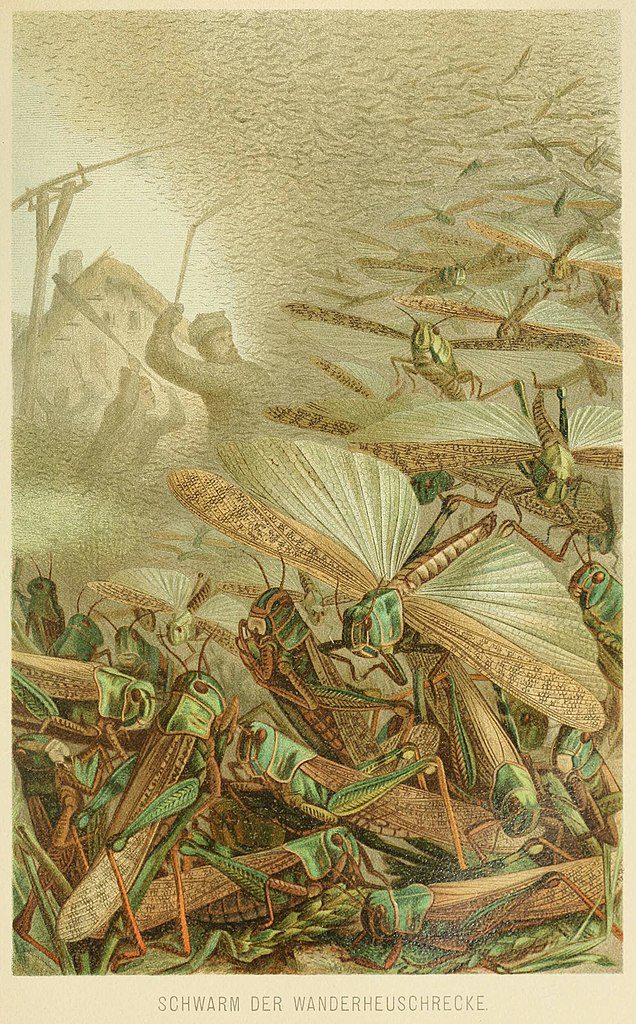

painting: A Swarm of Locusts by Emil Schmidt, in the public domain

A plague (in its generic meaning) is defined as “a destructively numerous influx or multiplication of a noxious animal; an epidemic disease causing a high rate of mortality”.

It is not that much of a stretch to define the explosion of humans on the planet, from a small range of 1-4 million individuals for our first million years on the planet (ie up until 7,000 years ago) to its current level of over 7 billion (a staggering and sudden 2,000-fold increase), as a plague. Our presence has crowded out every other species and brought about the 6th Great Extinction of life on our planet, which is advancing at an unprecedented rate.

The definition does conflate cause (the explosion in numbers of a “noxious” ie harmful species) and effect (the high rate of mortality), but in the case of our species we meet both definitions — we are unquestionably a harmful species that has exploded in numbers, and our presence has caused a very high rate of mortality everywhere on the planet.

What does it mean to be a plague? In the case of locusts, or dinosaurs, or viruses or bacteria, it essentially means that the “noxious” creature’s destructiveness to other organisms/species has massively destabilized the ecosystem, leading to sudden changes in the ecosystem that may take anywhere from a few years to eons to return to stasis.

Humans have tried to contain plagues in the past, but with very limited and temporary success; the sheer complexity of ecosystems and the rapid pace at which species can mutate in unpredictable ways to emerge as plagues, means that for the most part plagues have to be endured rather than prevented or even mitigated. We might argue that plagues serve an evolutionary purpose, since they tend to afflict creatures living in overcrowded and unhealthy conditions (eg the ‘plagues’ of avian and swine flu affecting the horror of factory farmed animals), and hence tend to restore rather than cause ecological imbalance. Without constant plagues of a variety of poxviruses affecting mosquitos, for example, mosquitos would constantly be multiplying unsustainably and causing ecological chaos everywhere as a result.

But some plagues seem to be evolutionarily unhelpful. Locust plagues, for example, occur when locust numbers start to surge in concentrated areas, usually as a result of an explosion of sudden new vegetation growth following a severe drought. The surge in numbers causes serotonin increases in the locusts which make them more gregarious, exacerbating the explosion of numbers. Is this an accident: nature going overboard trying to compensate and rebalance a sudden post-drought resurgence in plant life? We can only speculate, but it seems counter-productive when it inevitably leads to a mass die-off as the locusts exhaust their food supply — often followed by echo population explosions of rats eating the locust carcasses, and hence of rat diseases, including, of course, bacterial and viral plagues that further disrupt ecosystems.

Perhaps it’s natures way of self-limiting the exploding locust numbers themselves, although that would seem an exceptionally inefficient and harsh way of doing so.

Whatever the reason, there are some unpalatable parallels between locust plagues and human plagues. Throughout history, when human numbers have spiked beyond local carrying capacity, the propensity of our stressed species has often been to increase procreation even more (human population growth rates are, and have been, often highest in the world’s most ecologically desolated areas), worsening the overpopulation problem until it reaches the kind of crisis levels we are now seeing globally, which are inevitably followed by massive and ghastly die-offs.

On the other hand, in some species (like rats) overpopulation tends to have the opposite effect — fertility in crowded stressed conditions plunges, especially among non-alphas, bringing about depopulation and restoring the balance between numbers and food more quickly.

Rather than indicating that rats are smarter (at least at self-regulation) than humans and locusts, this may be a matter of confusing cause and effect.

A compelling argument has been made that many mammals tend to self-regulate their numbers proactively to match the available food supply. Daniel Quinn, in his Story of B, famously argues that this is so and that it applies equally to humans. Here’s the most pertinent extract:

Imagine if you will a cage with movable sides, so that it can be enlarged to any desired size. We begin by putting 10 healthy mice of both sexes into the cage, along with plenty of food and water. In just a few days there will of course be 20 mice, and we accordingly increase the amount of food we’re putting in the cage. In a few weeks, as we steadily increase the amount of available food, there will be 40, then 50, then 60, and so on, until one day there is 100. And let’s say that we’ve decided to stop the growth of the colony at 100. I’m sure you realize that we don’t need to pass out little condoms or birth-control pills to achieve this effect. All we have to do is stop increasing the amount of food that goes into the cage. Every day we put in an amount that we know is sufficient to sustain 100 mice — and no more. This is the part that many find hard to believe, but, trust me, it’s the truth: The growth of the community stops dead. Not overnight, of course, but in very short order. Putting in an amount of food sufficient for 100 mice, we will find — every single time — that the population of the cage soon stabilizes at 100. Of course I don’t mean 100 precisely. It will fluctuate between 90 and 110 but never go much beyond those limits. On the average, day after day, year after year, decade after decade, the population inside the cage will be 100.

Now if we should decide to have a population of 200 mice instead of 100, we won’t have to add aphrodisiacs to their diets or play erotic mouse movies for them. We’ll just have to increase the amount of food we put in the cage. If we put in enough food for 200, we’ll soon have 200. If we put in enough for 300, we’ll soon have 300. If we put in enough food for 400, we’ll soon have 400. If we put in enough for 500, we’ll soon have 500. This isn’t a guess, my friends. This isn’t a conjecture. This is a certainty. Of course, you understand that there’s noting special about mice in this regard. The same will happen with crickets or trout or badgers or sparrows. But I fear that many people bridle at the idea that humans might be included in this list.

His argument (which others like Jared Diamond and Richard Manning have also advanced) is that it was the invention (actually the discovery) of what is interchangeably called catastrophic, monoculture or totalitarian agriculture that enabled a surge in human food availability, which was immediately followed by a lock-step surge in human population. To the point that, with much of the planet now given over to such agriculture, our species has become a plague.

Let’s tie this back to locusts. Their explosion in numbers followed an explosion in post-drought plant life ie in their available food supply. Like the alders growing everywhere in first succession areas deforested by fire (or by incompetent human forest practices like clear-cutting), they are just stepping in to a system where there is suddenly lots of food and little or no competition. It takes evergreens, which eventually supplant the alders, much longer to take root in deforested areas — that’s why the bozos in charge of ‘forest management’ spray toxic chemicals like Roundup on ‘replanted’ monoculture forests, to kill the alders and make way faster for crowded stands of ‘commercial’ trees like Douglas firs, in the process making them more vulnerable to runaway wildfires and plant pest epidemics.

The seemingly paradoxical jump in fecundity of locusts when they are already overpopulated in the aftermath of a surge of new vegetation growth might be just an ‘unintentional’ evolutionary overreaction — nature making sure that this sudden increase in supply of one kind of food is kept in check by a sudden increase in supply of whatever species is next up the food chain.

If that’s so, then nature may be ironically attempting to bring the global explosion of food crops and farmed animals (which has encroached upon and threatened everything else that once lived in the ‘agricultural’ areas of the planet) back into balance by encouraging an explosion in the numbers of the one creature — humans — that seems best suited to quickly consume and eliminate that excess! If so, we should not expect our fate to be any different from that of the locusts once the gorging is over.

There is of course nothing that can be done about any of this. We didn’t choose to discover catastrophic agriculture, or to gorge ourselves on its excess until we are now on the verge of seeing our own numbers plummet, on the heels of precipitating the 6th Great Extinction. We’re just unfortunate players in what seems to be an evolutionary unfolding that is quickly approaching Endgame #6, with humans having played the only part we could have played. Not the part of the Crown of Creation, or the Pinnacle of Evolution.

The part of a Plague.