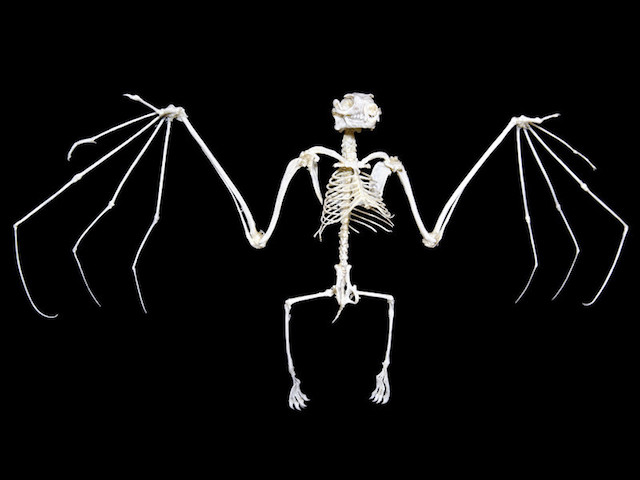

image via Ulf Parczyk on Jim Newman’s Facebook Page

Sometimes I feel as if I’m in possession of a great and important secret, but I live in a world where (almost) everyone else speaks a strange foreign language, so no one can understand me. “Hey!”, I call out, “Our civilization is on the verge of collapse, and there’s nothing we can do about it! It’s an extraordinarily complex, self-sustaining system, and it’s way out of our control. You can see that, right? And it’s all fine, right? And there’s no one to blame for that; we’re all doing our best — yes, even him! And in any case it doesn’t matter, because there is no civilization, no separation of anything from anything else, and no ‘us’ — those are all illusions, figments of our imagination. No, wait, not our imagination, since there is no ‘us’, they are just figments, appearances of, uh, ‘all that is’. That’s obvious, no? No? How can you not get that? Well at least you know that the problem behind almost all human illness is poor nutrition, but that, as we have no free will, and don’t want to eat what’s good for us, we won’t, so we’re not going to get better. You get that at least, right? What do you mean I’m crazy, there is evidence for all this. I’m not making this up. You’re the one that’s crazy, and sick too, you fool! Why do I even bother? No I won’t shut up. If you don’t like the truth, you leave! So there!” Hah! I sure told them…

Postscript on Links: Some of the links below contain qualifiers as to their source (usually referring to Pocket, a free news article digest service). I’ve started using these because they can penetrate annoying paywalls like those of the NYT. If they’re not working for you, or if you’re still hitting paywalls with these links, please let me know.

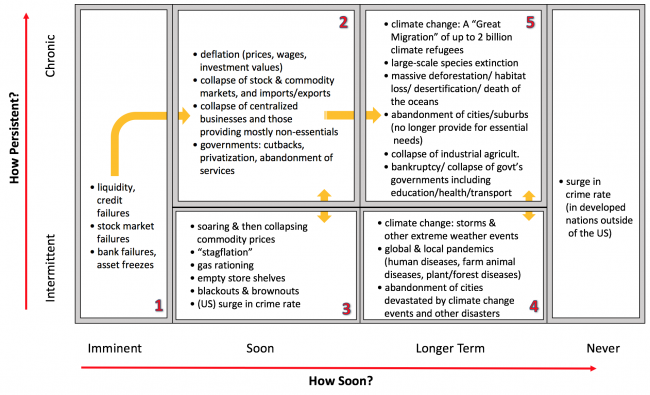

PREPARING FOR CIVILIZATION’S END

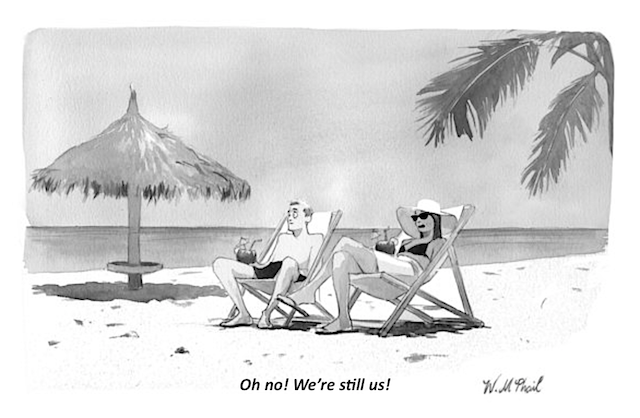

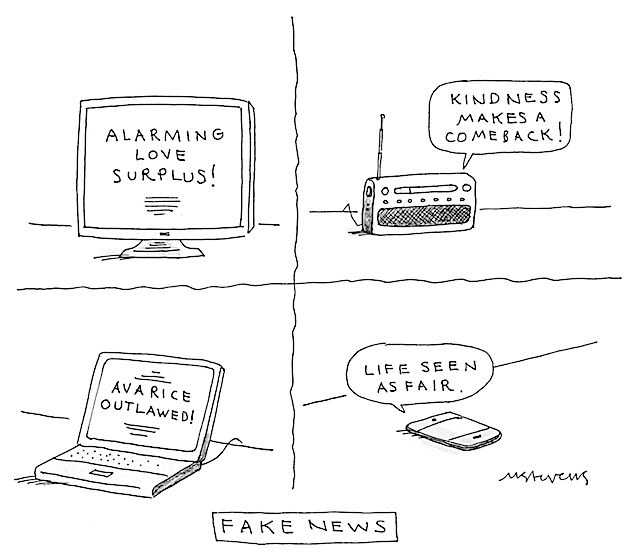

cartoon by David Sipress in The New Yorker

A Plea to Millennials: Tim Kreider pleads with America’s young people to fix everything that previous generations broke. It’s just a hopeless wishful rant, but its tone of exhaustion and bewilderment is telling:

My message, as an aging Gen X-er to millennials and those coming after them, is: Go get us. Take us down — all those cringing provincials who still think climate change is a hoax, that being transgender is a fad or that “socialism” means purges and re-education camps. Rid the world of all our outmoded opinions, vestigial prejudices and rotten institutions. Gender roles as disfiguring as foot-binding, the moribund and vampiric two-party system, the savage theology of capitalism — rip it all to the ground. I for one can’t wait till we’re gone. I just wish I could live to see the world without us.

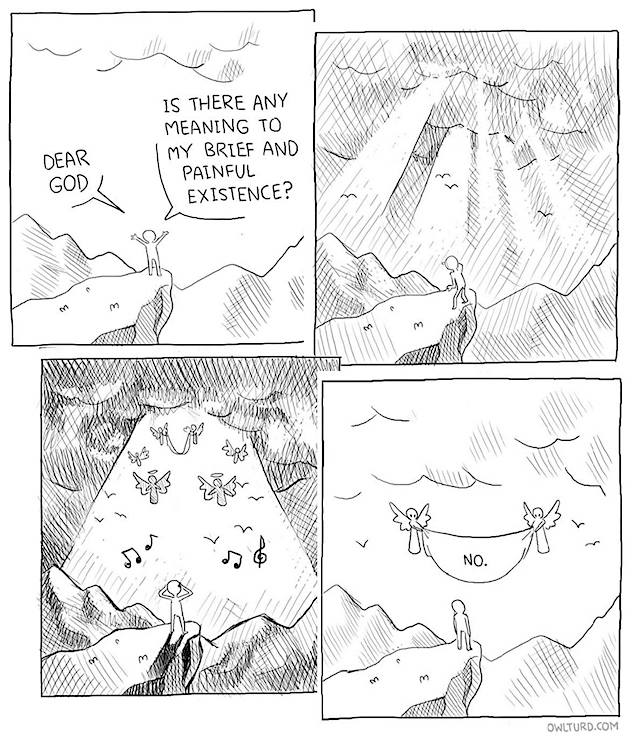

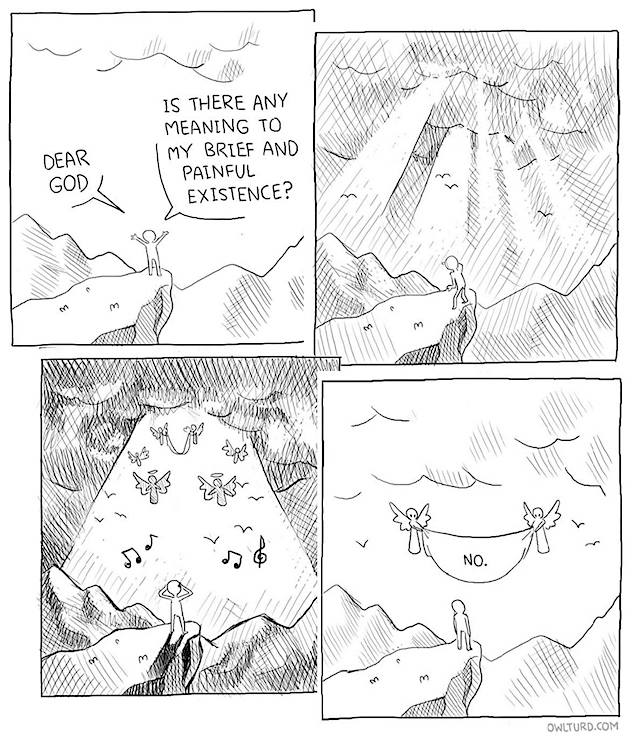

No One Is To Blame: RSA animation of an excerpt of philosopher Raoul Martinez’s explanation of the significance of discovering no one has free will, choice or responsibility for their apparent ‘decisions’ and actions, and hence no one is to blame; we’re all doing the only thing we can possibly do in the immediate circumstances we face each moment.

Rotten: Td0s writes about our culture’s unwillingness to do things well, and to pay to maintain the infrastructure we build and depend on:

Doing something well, making something that will last, is not prized in this culture. All that matters is completing the transaction. Once the purchase is made, the relationship is over and the poor sucker holding the bag can deal with the fall out. Empty and depressing malls ring towns of financially strapped families living in factory framed houses. Adults work wherever there is work for however long they have to while children are shuffled through overcrowded and underfunded schools until the bell rings and they are sent out into the meaningless wastes of suburbia. By some miracle a few of them turn out exemplary, while others muddle through it towards a life of alcohol and anxiety medication…

How do we tend to needs that have gone unmet for decades? How do we do social upkeep in a culture that wants us to believe that there is no society, only hard working winners, lazy losers, and a stop at Chick-Fil-A in between? How do we build places worth living in, and how do we make lives worth living? While trillions are spent on militaristically enforcing empire around the globe, our bridges and water mains crumble, and our population has sunk into such a deep pit of despair that it spends almost every non-working hour escaping into a drug or a fictional landscape.

Civilization’s Final Form: Brutus suggests we might be witnessing the end of our civilization culture precisely because as it crumbles it’s starting to look less and less like a culture at all:

We operate under a sloppy assumption that, much like Francis Fukuyama’s much ballyhooed pronouncement of the end of history, society has reached its final form, or at least something approximating it. Or maybe we simply expect that its current form will survive into the foreseeable future, which is tantamount to the same. That form features cheap, easy energy and information resources available at our fingertips; local, regional, and international transportation and travel at our service; consumable goods only a phone call or a few website clicks away; and human habitation concentrated in cities and suburbs connected by paved roads suitable for happy motoring. Free public education, such as it is, can be enjoyed until one is presumably old enough to discard it entirely. Political entities from nations to states/provinces to municipalities will remain stable or roughly as they have been for the last 70 years or so, as will governments. Suffice it to say, I don’t believe any of these things are capable of lasting much longer. Ironically, it’s probably true that what is described above is, in fact, society’s final form precisely because what follows won’t qualify anymore as a society.

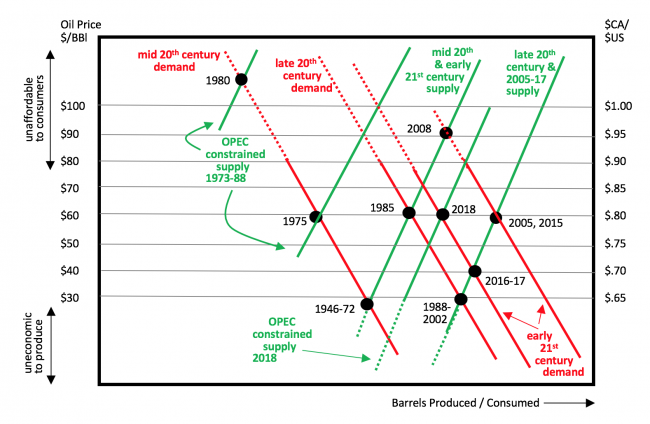

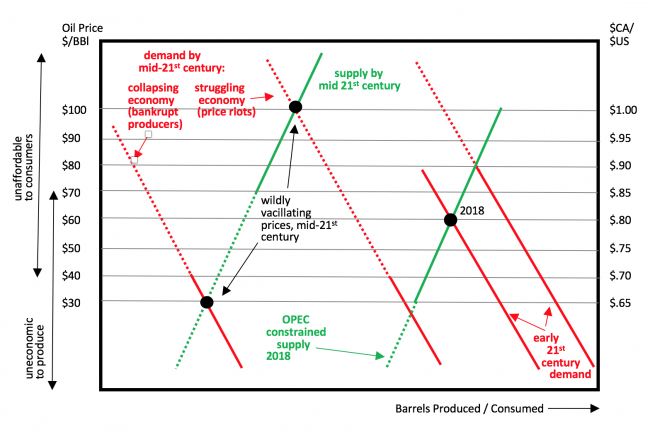

Why a Renewable Energy Society is a Pipedream: Despite technophiles’ dream of a world of clean abundant energy, the evidence clearly shows that our civilization will continue to rely mainly on hydrocarbons long past the point that hydrocarbon energy ceases to be affordable, precipitating a collapse of our economy and our industrial culture. Thanks to Sam Rose for the link.

Was Jared Diamond Wrong?: Recently a consensus has been achieved that the ‘scale problems’ of ‘civilized’ culture (lack of direct representation, inequality, hierarchy etc.) emerged with the development of ‘catastrophic’ agriculture (intensive, high-maintenance, large-scale monoculture). Now David Graeber argues that this wasn’t the case: all human societies, he argues, have employed a mix of egalitarian and hierarchical social structures, even the earliest tribal societies.

Is Civilization a Wetiko Culture?: Many ancient cultures have a concept called wetiko, a disease that induces cannibalism or vampirism (thanks to Philip Kippenberger for pointing me to this). Stories about it are cautionary tales against excessive acquisitiveness and disconnection from community. A new study suggests our culture is what they were warning about (but falls short of asking the more intriguing question whether, because of our large brains’ propensity for abstraction and seeing ourselves as apart from the rest of life, human cultures will inevitably succumb to the disease):

When Western anthropologists first started to study wetiko, they [identified] two traits that are relevant for thinking about cultures: (1) the initial act, even when driven by necessity, creates a residual, unnatural desire for more; and (2) the host carrier, which they called the ‘victim,’ ended up with an ‘icy heart’— i.e., their ability for empathy and compassion was amputated.

The reader can probably already sense from the two traits mentioned above the wetiko nature of modern capitalism. Its insatiable hunger for finite resources; its disregard for the pain of groups and cultures it consumes; its belief in consumption as savior; its overriding obsession with its own material growth; and its viral spread across the surface of the planet. It is wholly accurate to describe neoliberal capitalism as cannibalizing life on this planet. It is not the only truth—capitalism has also facilitated an explosion of human life and ingenuity—but when taken as a whole, capitalism is certainly eating through the life-force of this planet in service of its own growth.

LIVING BETTER

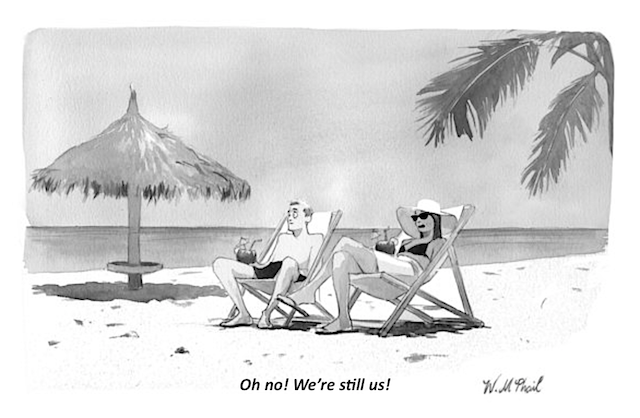

cartoon by Will McPhail in The New Yorker

Food as Medicine: Nutritionfacts.org’s Michael Greger’s TEDx talk about why almost all the major causes of death in western society are attributable to poor nutrition and the industrial food system.

Howe Sound Ballet: My friend Bob Turner captures astonishing footage of seals, sea lions and massive schools of anchovies right in Snug Cove, Bowen Island.

Music As Life and Death: His friend James Stewart writes a brilliant biography of Eric Sun, violin virtuoso and Facebook genius, an exemplar of how to live with purpose and how to die with dignity.

Rent Now, Buy Never: Vancouver is using modified shipping containers to create a network of neighbourhood lending libraries for tools and recreational gear that people only use occasionally, each run by a neighbourhood co-op.

Re-Thinking Our Reading Problem: Perhaps the problem with our high rates of functional illiteracy, and poor skills at reading and understanding complex material, are due less to lack of literacy teaching in schools, and more to a lack of breadth and depth of knowledge about a wide range of subject matter. If we learned more about subjects (from oral discussions, demonstrations, visits etc) before we tried to read up about them, in other words, our reading might go a lot further than it does without that context.

Why Capitalism, Modern Management and Bonuses Lead to Poor Work Performance: What apparently motivates us to do our best work, says Dan Pink, is not monetary rewards (beyond a comfortable salary); it is autonomy (degree of control over what we do), mastery (the desire to achieve a high level of competence at what we do), and purpose (a shared sense that what we do is important in the world, and why). Capitalism, in contrast, rewards obedience, cost reduction, and coercive marketing.

In the Market for a Laptop, Phone or Camera?: Take a look at ProductChart, which allows you to select all the criteria you care about and then shows a chart comparing benefits vs cost, with links for more information. Seems to be free of hidden sponsorships and biases. Thanks to Tree Bressen for the link, and the one that follows.

The Unknown Language of the Jedek: A new language has been discovered, almost by accident, in Malaysia, and neither the language nor the culture of its people seem to support or encourage misogyny, violence, private ownership, punishment of criminals, or specialized professions or jobs.

The Secret of a Great Email Message: A message from Steve Jobs about whether HarperCollins should publish e-books through Apple rather than Amazon, serves to point out the essential elements of a short, persuasive, articulate message.

POLITICS & ECONOMICS AS USUAL

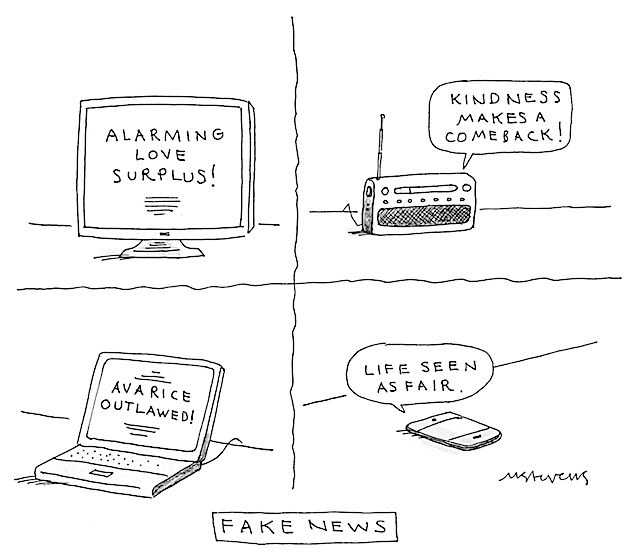

cartoon by Mick Stevens in The New Yorker

What Money Can’t Buy, and What It Shouldn’t: Professor Michael Sandel explains the corrupting influence of untrammelled ‘market’ capitalism, where everything has a price and the ‘market’ (ie who has wealth and power) entirely determines what gets done and made, and what doesn’t.

Corporations Loathing Customers: Corporations have done their damnedest to automate and outsource the annoying nuisance of employees. Now they are turning their loathing to that other class of people, their customers. It started with forcing you to deal with call centres (whose staff are paid to prevent customers from any access to management and any facility to improve processes or obtain satisfaction), and online ‘community FAQs’ that essentially outsource customer service to — other customers! They also use ‘community engagement’ and ‘focus groups’ as fraudulent means to pretend to actually listen to customers, when all they really want is for the customers to shut up and buy.

Our Broken Democracies: The smug reaction of the Democrats waiting for Trump to implode so they can resume their rightful place in power (in bed with Wall Street), is reflected in equally egregious actions (and inaction) almost every democracy in the world, as the incapacity of centralized governments to address the challenges of our time becomes more obvious. In Canada, the once-left NDP party’s provincial governments are threatening each other and showing their true anti-environmental colours, as the Alberta NDP touts tar sands energy and the BC NDP goes ahead with the abominable and unnecessary Site C hydro dam (with the complicity of the Greens), to placate labour and defend its base. Meanwhile, at the federal level, the governing so-called Liberals are reneging on both their environmental and proportionate representation promises.

Blowing the Whistle on the Times: James Risen explains why he quit working as an investigative reporter for the NYT when he learned how complicit they were in working with the federal government’s propaganda and war machine, and why the NYT signed up for this devil’s bargain to access and release information that would otherwise never see the light of day.

The Stock Market Has Nothing to Do With the Economy: Almost all investments (and savings of any kind for that matter) are owned by a tiny proportion of the populace. I could add that the “official” unemployment rate and inflation rate and the number of people in (mostly lousy underpaid) jobs and the GDP have nothing to do with the economy either.

And the Housing Crisis is All About Globalization: The unavailability of affordable housing in the world’s desirable cities has little to do with local or even national politics, or with immigration — it’s all about global money from the world’s rich elite seeking safe places to park the staggering wealth they have accumulated. And it’s not just housing they’re gobbling up — it’s arable and resource-rich land as well.

Why Blacks Live in Mostly-Black Neighbourhoods: It is because they aren’t safe living in white neighbourhoods. Not safe from violent whites. Not safe from police. It’s not because they want to live in segregated neighbourhoods. Thanks to Tree Bressen for the link.

The End of the Job and the Age of Drudgery…: As the obsession with profits and competition leads to endless outsourcing, corner-cutting, quality-reduction and benefits-reduction, we have witnessed in a generation the end of the ‘job’, a bargain in which you once got security and the guarantee of a decent living wage, in return for promising to offer one master your skills and experience for a lifetime. Everyone is now a freelancer, but in a world where the rules are fixed in favour of the rich and powerful oligarchs, for most this is no improvement, just a life-sentence to long hours of drudgery in multiple work environments with no opportunity for promotion and no security whatsoever.

…and Why That Drudgery Arose: Umair Haque describes the brutal world that leads to this drudgery as a predator society, in which the only ‘successful’ young workers are those who emulate the brutal predation of corporate oligopolies on people, resources and nations. This predation has evolved because of what Umair calls a broad social pathology with these qualities (Thanks to Antonio Dias and PS Pirro for the links):

Americans appear to be quite happy simply watching one another die, in all the ways above. They just don’t appear to be too disturbed, moved, or even affected by [pathologies like] their kids killing each other, their social bonds collapsing, being powerless to live with dignity, or having to numb the pain of it all away. If these pathologies happened in any other rich country — even in most poor ones — people would be aghast, shocked, and stunned, and certainly moved to make them not happen. But in America, they are, well, not even resigned. They are indifferent, mostly…

A predatory society doesn’t just mean oligarchs ripping people off financially. In a truer way, it means people nodding and smiling and going about their everyday business as their neighbours, friends, and colleagues die early deaths in shallow graves. The predator in American society isn’t just its super-rich — but an invisible and insatiable force: the normalization of what in the rest of the world would be seen as shameful, historic, generational moral failures, if not crimes, becoming mere mundane everyday affairs not to be too worried by or troubled about.

FUN & INSPIRATION

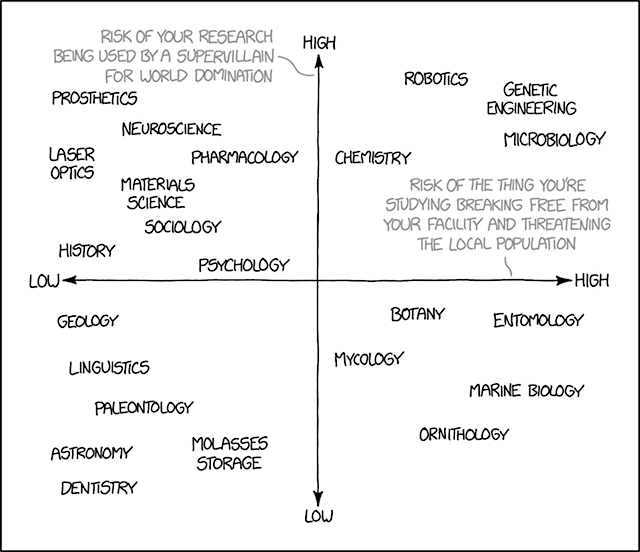

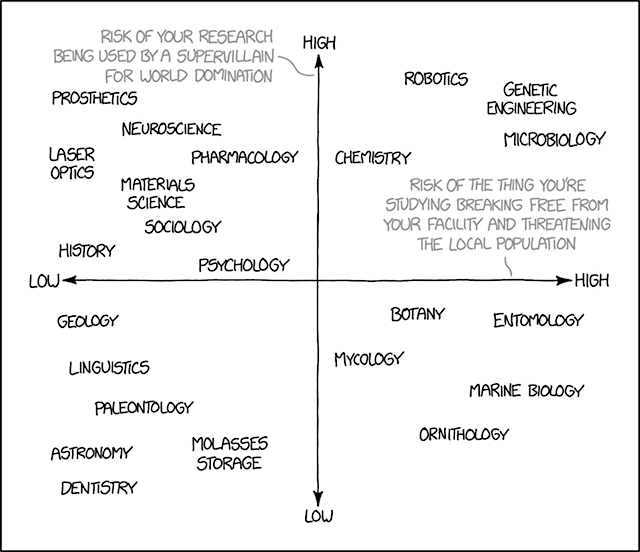

from the comic xkcd, “Research Risks”

The Annals of Pard: Brilliant, observant, compassionate, imaginative writing from the late incomparable Ursula Le Guin, about her cat, Pard.

Show Them the Way That You Feel: Choir! Choir! Choir! sings James Taylor’s Shower the People, hundreds strong.

Boys Will Be Boys: As mothers take over from fathers tending adjacent nests of baby albatrosses on the island of Kaua’i (just a few miles up the road from where I’m staying), one of the males moves too close to the other and a brief scuffle ensues. Their mates are not impressed.

Never Gonna Dance Again: Young virtuoso guitarist Alexandr Misko does a stunning version of George Michael’s Careless Whisper.

Life on Earth 3.5B Years Old?: Scientists, in disarray over discoveries all over the planet that indicate global human presence more than 100,000 years ago, are now struggling to make sense of fossils that indicate primitive life all over the planet as long as 3.5 billion years ago, a billion years before it was previously thought possible.

Hard to Know When to Give Up the Fight: Lovely animation of the moving Patti Griffin song Rain.

“What important truth do very few people agree with you on?”: The answer to this question, says Peter Thiel, probably indicates the work you’re meant to do, the greatest entrepreneurial opportunity waiting for you to jump on it.

March 31st is International Quit Your Crappy Job Day: Discover if it’s the right time for you to find more meaningful work. Thanks to Tree Bressen for the link.

Whoever is There Come on Through: Wonderful writing about friendship and loneliness by Irish writer Colin Barrett. If you want to learn how to write dialogue that brings out a character’s personality and passions, study this. And read this interview with Colin too.

What Music Videos Could Be: Stunning, carefully-composed ultra-HD videography combine with gentle music in a series of shorts about food and life in (a bygone era in?) remote parts of China. This one is about matsutake mushrooms. Thanks to Ben Collver for the link, and the one that follows.

Mutant Marbled Crayfish Charm the World: A new species of crayfish that clones itself, is astonishingly prolific, and produces only females, has been found in the wild (its origin is unknown, though some speculate it came from a German laboratory, though its biological predecessors live only in the southern US), and is now a thriving import business. The fact that it’s a clone, however, means limited resistance to disease (no variability in genetics) so it’s not sure how long its population explosion will last.

THOUGHTS OF THE QUARTER

From PS Pirro, from Listen: “Words are my hammer. I pound and I pound on what is not and never will be a nail.”

From the late Ursula Le Guin, from Steering the Craft:

Recognition of syntactical constructions used to be taught by the method of diagramming, a useful skill for any writer. If you can find an old grammar book that shows you how to diagram a sentence, have a look; it’s enlightening. It may make you realize that a sentence has a skeleton, just as a horse does, and the sentence, or the horse, moves the way it does because of the way its bones are put together. A keen feeling for that arrangement and connection and relation of words is essential equipment for a writer of narrative prose. You don’t need to know all the rules of syntax, but you have to train yourself to hear it or feel it, so that you’ll know when a sentence is so tangled up it’s about to fall onto its nose and when it’s running clear and free.

From Anna Tivel, Illinois:

Underneath the heavy sky, the highway shines

A razor blade cutting down to bone

Nothing left to do but hold the wheel and drive

The dark of night, the dim light on the road

All the way from Illinois, a thousand miles of waiting for

A gentle touch, a kind, believing word

All the way from Illinois, and not one to be heard

Tell me all the ways to make a day go by

In an aeroplane high above the earth

Or standing in the kitchen in an awful fight

The brightly colored blood of ugly words

All the way from Illinois, a box of clothes, a can of oil

The promise of a place to settle down

All the way from Illinois, and not one to be found

And nothing hurts like crying on a long drive home

Nothing worse than hiding in the dark alone

From the beautiful lights of a dangerous love

Shattered glass, a photograph of a broken heart

A crack along the windshield of the world

The shape of something running in the untamed dark

The howling out of freedom and of hurt

All the way from Illinois, the radio, the rain, the road

The dream of finding out just what is love

All the way from Illinois, and turns out nothing was

From Peter Everwine: The Day:

We walked at the edge of the sea, the dog,

still young then, running ahead of us.

Few people. Gulls. A flock of pelicans

circled beyond the swells, then closed

their wings and dropped head-long

into the dazzle of light and sea. You clapped

your hands; the day grew brilliant.

Later we sat at a small table

with wine and food that tasted of the sea.

A perfect day, we said to one another,

so that even when the day ended

and the lights of houses among the hills

came on like a scattering of embers,

we watched it leave without regret.

That night, easing myself toward sleep,

I thought how blindly we stumble ahead

with such hope, a light flares briefly—Ah, Happiness!

then we turn and go on our way again.

But happiness, too, goes on its way,

and years from where we were, I lie awake

in the dark and suddenly it returns—

that day by the sea, that happiness,

though it is not the same happiness,

not the same darkness.