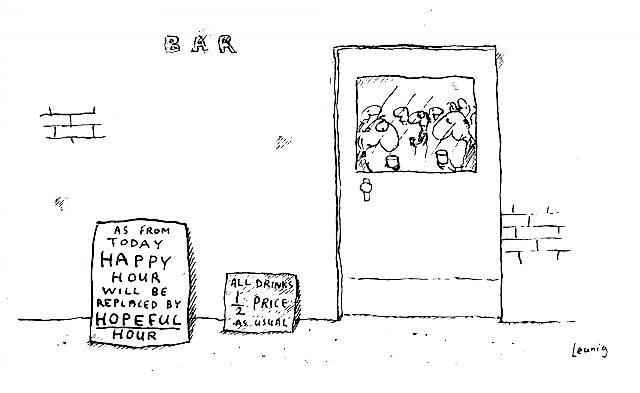

our civilization, it seems to me

our civilization, it seems to me

is like an old man with alzheimer’s;

it has its good days and its bad days,

but on the whole the progress of the disease seems slow but relentless

and the prognosis doesn’t look good —

there’s more crashing into walls and other sudden mysterious crises each year

and the recovery, each time, seems a bit slower.

on the surface it seems to be functioning just fine,

though more and more helpers have been recruited to stop by

and do the things it use to be able to manage by itself;

it doesn’t seem able to feed itself any more.

and it used to be so clear, so coherent and reliable,

it seemed possible to believe it could live on forever,

growing ever-bigger and better and stronger

and looking after all the generations who depended on it.

the real problem now is the infrastructure,

the hidden stuff, the stuff inside that’s been neglected too long

denied, ignored, in the hope the problems will somehow just go away,

consequence of decades of unhealthy behaviour;

we’ve seen the images, the scans, and it’s nasty in there,

lots of stuff festering, rotting, falling apart, beyond repair.

and then there’s the stuff outside, the externalities,

the mess beyond the centre, where the waste was thrown

without any real intention to clean it up later

and now the whole place is a mess,

and the stuff that’s needed is harder and harder to find.

and what happened to the old energy?

there used to be such enthusiasm, such magic, such joy,

such belief in the eternity of everything;

now it seems it takes more and more effort to do the same thing,

and there’s a lot of stumbling and coughing.

and the cost of maintaining everything just goes up and up,

90% of the cost of maintaining health, they say

comes in the last 10% of one’s life,

will that be true of this once-mighty and resilient culture?

and is it worth that investment

for the quality of life it might provide

for just another short while?

it may be time to move it to a home where it’s comfortable,

where it’s not so exhausting trying to look after its needs

and once again get on with our own lives, beyond it.

it may be time to think about the wisdom of life support

and ask whether it’s a favour to it or anyone

to keep it alive, another day, another year.

but today seems a not-too-bad day, shuffling forward

one step at a time; maybe we need to get back to work

so it can be fed, medicated, bandaged up

one more day, it’s just one more day —

how would we ever live without it?

we can decide what to do about it tomorrow.

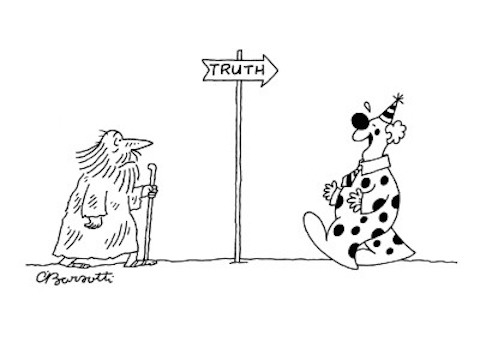

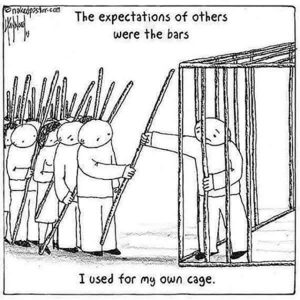

cartoon above by the Naked Pastor, David Hayward

~~~~~

PREPARING FOR CIVILIZATION’S COLLAPSE

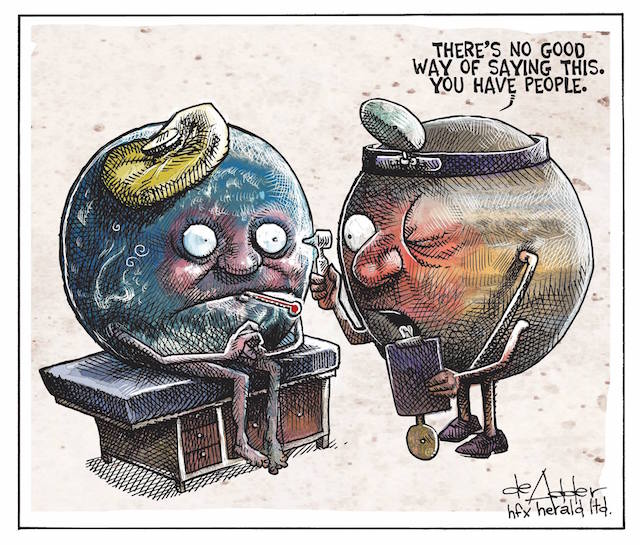

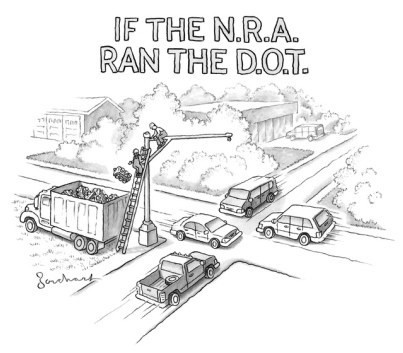

cartoon by Michael de Adder in the Halifax Chronicle Herald — thanks to Karen Runge for the link

To Change Everything, Start Here: Crimethinc offers a smartly written manifesto for anarchism (“a philosophy that advocates self-governed, stateless societies based on voluntary non-hierarchical institutions and free associations”) starting with how you see yourself, your own beliefs and behaviours, your relationship with others, how you perceive the problems we face in the world (and how they’re all connected), and the principles and power dynamics that underlie a completely different way of thinking and seeing. It’s inspiring, liberating, and thought provoking. Thanks to Tree for the link.

td0s Reads the Signs: The articulate author of Pray for Calamity describes what he’s seeing in the map of our immediate future:

Simply stated, this is what I see: A period of economic depression is on the wind… Where it all leads is too far out to say… It is when a majority of the significant trend-lines slump downward that we can say with certainty a society is in decline… There will be a shake out of never-to-be-solvent again institutions, and a generalized acknowledgement of a paradigm of “hard times” being upon us. Natural disasters will be harder and harder to recover from as they will strike more often in regions where status quo thinking believes them too unlikely or impossible and this will combine with a financial inability to afford repair. Politically, people will seek easy and incorrect answers, so on that front we will have nothing new in thinking modality, but we will see new lows in practical application.

Dave Talks About Preparing for Collapse: Lone Raven at the Dispossess Podcast interviews yours truly. About 75 minutes long.

What Will We Use Renewable Energy For?: Jason Hickel asks the difficult question about whether our zeal for renewable energy is so that we can continue to fuel destructive and unsustainable activities. He think we will just use the energy to “raze more forests, build more meat farms, expand industrial agriculture and deplete our soils, produce more cement, and fill more landfill sites, all of which will pump deadly amounts of greenhouse gas into the air. We will do these things because our economic system demands endless compound growth, and for some reason we have not thought to question this.” Thanks to Shasta Martinuk for the link.

One Percent Away From Disaster: Low interest rates penalize savers and those on fixed incomes, and reward gamblers, big banks and heavy borrowers (including most big corporations). A recent study indicates that an interest rate rise as small as 1% would put nearly a million Canadian borrowers under water — unable to pay their debts with current sources of income. The situation is the same in most “affluent” nations. That’s why regulators and politicians keep interest rates artificially low — way less than the real rate of inflation — and we all suffer as a result.

~~~~~

LIVING BETTER

driftwood horse by Heather Jansch

The Hows and Whys of Financial Regulation: The heroic Janelle Orsi at the Sustainable Economies Law Centre explains why (and by who) the myriad of complex and costly financial and fiduciary regulations that govern corporations were established, and why a completely different set of regulations is needed for small, cooperative, not-for-profit enterprises. This 13-minute video is essential to understanding the sharing economy and the obstacles it faces. Thanks to Tree for the link, and the two that follow.

A Superb Apology: A news reporter demonstrates how to admit you’ve done something wrong, in a way that helps others learn as well, and do it with class.

Please Unsubscribe: Chris Clark, co-founder of the Reinventing Organizations wiki, reminds us to be wary of promises and demands (some of them self-initiated) to become more efficient, productive, or better in other ways, especially when they consume valuable time and reinforce “behaviors that don’t actually make a difference, perspectives that limit our capacity to make a difference, and mindsets that cause us to act from fear of difference: scarcity, comparison, and ego.”

Coping With Climate Change Distress: This PDF from Australia has a little too much cognitive behavioural content for my liking, but the idea is a good one, and there are many sound coping strategies for coming to grips emotionally with the grim reality of climate change in it. Thanks to my friends at NTHELove for the link.

The Sea Shepherd Sails On: The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society has recently been in the Salish Sea near where I live, researching and protesting the scourge of “salmon farming”.

The Pill You’re Not Allowed to Take: The economics of the pharmaceutical industry demand that no medicine be commercially developed that actually cures an illness (no profit in that), and that no research or support be given to the benefits of unpatentable medicines. That’s one reason, explains Michael Pollan, why hallucinogens have been off-limits for research and prescription for anxiety, depression, addiction and a host of other chronic medical conditions since the 1960s, despite their promise not just as a treatment, but as a cure. Meanwhile, we keep using the self-defeating Alcoholics Anonymous 12-step type programs and other cognitive behavioural change methods, even though they have never worked. Maybe the therapists, like the pharma companies, are not unhappy that their patients are never cured and have to keep coming back for more?

Not Even Greens Understand Complexity: The City of Victoria BC dumps all its raw sewage into the ocean. That’s outrageous, right, and even at a cost of $1 billion it needs to stop, right? Well, maybe. Read this for an explanation why apparently obvious “green” solutions to some complex problems may not be the right answer. Outstanding writing from Mike Ruffolo.

The Forest as “Natural Economy”: Rob Hopkins draws a metaphor between the way in which the forest self-manages and self-optimizes, and the way that a more healthy economy than the one we have today, would naturally do likewise.

~~~~~

POLITICS AND ECONOMICS AS USUAL

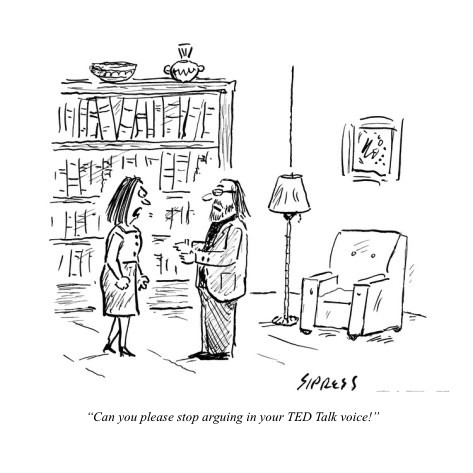

New Yorker cartoon by David Borchart

What “the Talk” is Really Saying: Ta-Nehisi Coates: “In the black community, it’s the force they deploy, and not any higher American ideal, that gives police their power. This is obviously dangerous for those who are policed. Less appreciated is the danger illegitimacy ultimately poses to those who must do the policing. For if the law represents nothing but the greatest force, then it really is indistinguishable from any other street gang. And if the law is nothing but a gang, then it is certain that someone will resort to the kind of justice typically meted out to all other powers in the street.”

The Private Legal System for Multi-National Corporations: Big companies suing foreign governments for the right to pollute and pillage worldwide (embedded in so-called “free trade” laws) have decided they can’t afford to lose, so they have set up their own parallel legal system to ensure they don’t, and to ensure governments can’t afford to fight them.

Power Concedes Nothing Without a Demand: My friend Paul Cienfuegos explains how Monsanto and other execrable corporations get away with coercing politicians to pass laws that contravene the public interest, often quite overtly. He quotes Howard Zinn: “Civil disobedience is not our problem. Our problem is civil obedience. … Our problem is that people are obedient while the jails are full of petty thieves, and all the while the grand thieves are running and robbing the country.”

The Fight Against Getty: A famed photographer is billed and threatened by Getty for unauthorized use of her own images, images that she’d placed years ago in the public domain. She uses Getty’s own billing algorithm to compute the damages they owe her for their misconduct. I’d love to see these bastards, the Monsanto of digital intellectual property, driven out of business. Unfortunately, similar unscrupulous organizations lurk everywhere, especially online — the 1000% ticket scalpers, the “virus cleaners”, the exploiters of gullible seniors, and all the rest. It’s a major problem in the unregulatable ‘wild west’ of the internet. Can we label it “digital terrorism” and hence get some big money and resources to fight it? (Thanks to Tree for the link.)

The Collapse of Canada’s Political Left: Like its British cousins, Canada’s two prominent progressive parties are killing themselves. The NDP leader, like Britain’s Labour Party leader, is hanging tough despite a widespread call for his resignation and his general off-putting irascible nature and proven unelectability. At this critical point when PM Trudeau has abandoned his party’s traditional progressive values and shifted the “Liberals” to centre-right and needs to be called to account, the NDP is now stuck with its lame-duck leader for at least another year until his permanent replacement is chosen (and no quality candidates have surfaced). Meanwhile, Canada’s Greens have imploded, as much of its leadership has quit or been purged by its only elected member over the party’s overwhelming adoption of modified sanctions against Israel, which the party’s leader thinks unconscionable and “extremist” (she threatened to resign unless the motion was rescinded, leading to capitulation, the purge and many resignations). So now Canadians are left, like our American cousins, with no progressive electable alternative. No wonder no one trusts politicians — egomaniacs and prima donnas all.

Canadian Nuclear Boss Jokes About Whistleblowers: We may have a new “Liberal” federal government but the corrupt crony capitalism of the Harper era rolls on. We have the National Energy Board holding secret meetings with corporations and politicians before ruling on their pipeline proposals, and nuclear energy execs censoring investigative reporters and ridiculing whistleblowers who expose serious safety concerns. The National Observer, the Tyee, the CBC (increasingly cautiously) and the Toronto Star seem to be the only Canadian media doing any investigative journalism any more.

The Insanity of BC’s Site C Dam: An expert agrologist explains the disastrous impact the imminent and massive Site C dam in northern BC will have on food, food security, nutrition, community resilience, and First Nations and water sovereignty. Not to mention BC’s financial solvency. But the provincial government’s zeal to export “renewable” power (and eventually water) has blinded it to the sustained opposition the project has faced, and Trudeau seems on the verge of approving it federally.

~~~~~

FUN AND INSPIRATION

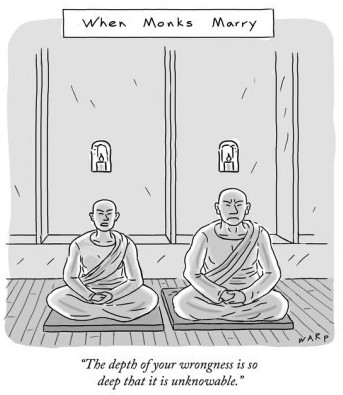

New Yorker cartoon by Kim Warp

The Oxford Style Guide: A short and wonderfully-written guide (PDF) to modern English usage. Quick: Which of the following 22 examples are poor style: ie, eg, etc, 50k, T S Eliot, the Canadian federal government, Mr Jones, St Andrews, the Island (referring to Bowen Island), there were 12 attendees at one session and 2 at the other, the event is at 1pm, the event runs October–December, Jesus’s disciples, CDs are obsolete, dot the ‘i’s and cross the ‘t’s, It was – I think – bright green, email, a highly respected woman, I think so…but I’m not positive, BSc, fundraising, the internet.

Skunk Family Meets Bicyclist: In case you’re the one person left in the world who hasn’t seen this charming awwww-some one-minute video.

Scroll Down to See Answer: The ever-brilliant xkcd presents a true-to-scale (22 screens long) graphic showing Earth’s surface temperature over the past 22,000 years. Hilarious and terrifying. Thanks to several people who pointed me to this.

Why We Build the Wall: Anaïs Mitchell explains, in song, why Drumpf and his supporters want to build walls. More of her wonderful lyrics here (PDF) (check out especially Quecreek Flood).

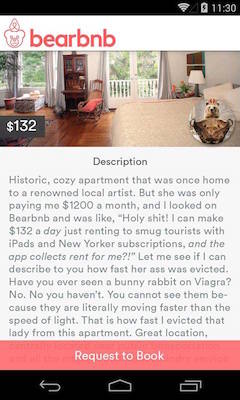

Bearbnb: Bowen Island has a black bear cub. Happens every few years, and they cause great upset among the local chickens and their owners, and then either swim away to better pickings or get shot. Our other great local controversy is the conversion of monthly rental space to airbnb, creating a shortage of affordable rental accommodation for residents. Bowen resident Andrew David put the two scandals together and came up with the priceless ad shown at right.

Bearbnb: Bowen Island has a black bear cub. Happens every few years, and they cause great upset among the local chickens and their owners, and then either swim away to better pickings or get shot. Our other great local controversy is the conversion of monthly rental space to airbnb, creating a shortage of affordable rental accommodation for residents. Bowen resident Andrew David put the two scandals together and came up with the priceless ad shown at right.

The Whole Point of the Dancing is the Dance: Great short film Why Your Life is Not a Journey, by David Lindberg, with words and narration by Alan Watts. Your life was never about a destination; “It was a musical thing, and you were supposed to sing, or to dance, while the music was being played”. Thanks to my friend Jessica Mitts for the link, and the one that follows.

Girls and Sex: The New Landscape: Peggy Orenstein tells some hair-raising stories about what teenage girls/women now have to put up with, and advises us how we can help them navigate it, and what we can learn from the skills they’ve had to develop.

Who Will Touch Me All the Time?: Katie Tandy’s stunning and courageous celebration of body and life full on. Probably NSFW. “Please dance with me, we’re all going to die; you might as well sway with my body next to yours.”

Winning at Any Cost: Malcolm Gladwell, who has successfully argued that almost all of the recent world records and other unprecedented athletic performances are drug-enhanced, explains via video the ethics of abusing your body for money and fame. Yet it continues.

Carpool Karaoke: Michelle Obama disarmingly sings and laughs up a storm. An amazing and refreshing video. If only politicians could behave this authentically. Though perhaps… uh, never mind.

Eleven Beautiful Untranslatable Japanese Words: To convey any of these in English would take a whole awkward phrase. Thanks to Cheryl Long for the link.

The Art of Rebecca Clark: The wild creatures in her drawings seem almost alive, ready to tell you something important.

The Abuse of Feel-Good Cop Videos: You know the police-sponsored ones where the heavily armed cop comes up and surprisingly just gives someone an ice cream. “Just as abusive relationships don’t end with flowers, abusive police systems don’t end with ice cream.” Thanks to Jeff Brakensiek for the link.

All About Nothing: A (one hour) film about non-duality. Quirky, silly and fun. And, of course, Dutch.

~~~~~

THOUGHTS FOR THE QUARTER

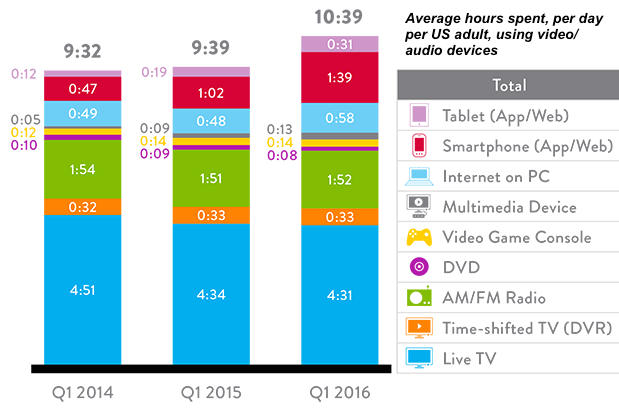

recent survey by Nielsen: for teenagers and young adults the average is only 7 hours a day, rising to over 11 hours for seniors, so the increase is due largely to population aging; teenagers spend about 2 3/4 hours on each of TV and smart phones and almost no time on PCs; PC usage peaks at around age 40 at about 1 1/4 hours/day; seniors watch more than 3x as much TV as teenagers and young adults

The Eliotesque Poetry of Anna Tivel: Reverie (also check out her lyrics to Black Balloon):

the streetlights are diamonds, the sidewalk a bed, of boot heels and garbage and cigarettes

and only the hopeless and lonesome are left, to pin up the night and go home

and i don’t believe that a fortune is told by the turning of cards, by the swinging of stones

but still i’m here hoping for what i can’t hold, for some kind of sign from above

so turn out the lights, let the diamonds be damned; a reverie is sweeter in the dark

and i don’t got nothing but two empty hands and this slow burning flame of a heart

and midnight comes rolling all bottles and bags; they come to rest soft in the park

and a beautiful woman, her voice made of glass stirs in a dream in the dark

and i don’t believe that the future is told by the weight of a word, but by the way it’s spoke

and still i’m here holding your name in my throat and isn’t it sweet on my tongue

and the dawn glows, and it spreads like a spill in the shadows, someone whispers:

it will be alright

the streetlights are faded, the sidewalk a song, of footsteps, and papers, and telephones

and darling it’s raining, come take me back home, it seems that i’ve seen quite enough

and i don’t know which way i’m bound to believe: the story itself, or the space between

but still i’m here wiping my eyes on my sleeve at the beautiful world waking up

Bridge, by Jim Harrison, who died this past March (thanks to wordsfortheyear.com for the link):

Most of my life was spent

building a bridge out over the sea

though the sea was too wide.

I’m proud of the bridge

hanging in the pure sea air. Machado

came for a visit and we sat on the

end of the bridge, which was his idea.

Now that I’m old the work goes slowly.

Ever nearer death, I like it out here

high above the sea bundled

up for the arctic storms of late fall,

the resounding crash and moan of the sea,

the hundred-foot depth of the green troughs.

Sometimes the sea roars and howls like

the animal it is, a continent wide and alive.

What beauty in this the darkest music

over which you can hear the lightest music of human

behavior, the tender connection between men and galaxies.

So I sit on the edge, wagging my feet above

the abyss. Tonight the moon will be in my lap.

This is my job, to study the universe

from my bridge. I have the sky, the sea, the faint

green streak of Canadian forest on the far shore.

From Mark Forsyth’s The Elements of Eloquence, a remarkable reminder of the rules of adjective order that fluent English speakers follow without quite knowing why (thanks to my old friend Dave Snowden for the link):

…adjectives in English absolutely have to be in this order: opinion-size-age-shape-colour-origin-material-purpose Noun. So you can have a lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife. But if you mess with that word order in the slightest you’ll sound like a maniac. It’s an odd thing that every English speaker uses that list, but almost none of us could write it out.

From Thomas Kuhn, on how change comes from generational rollover, and takes 15 years or longer to occur, rather than from persuasion or coercion (thanks to Vinay Gupta for the link):

Max Planck, surveying his own career in his Scientific Autobiography, sadly remarked that “a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it”.

From David Foster Wallace, from Up Simba!:

If you are bored and disgusted by politics and don’t bother to vote, you are in effect voting for the entrenched Establishments of the two major parties, who please rest assured are not dumb, and who are keenly aware that it is in their interests to keep you disgusted and bored and cynical and to give you every possible reason to stay at home doing one-hitters and watching MTV on primary day. By all means stay home if you want, but don’t bullshit yourself that you’re not voting. In reality, there is no such thing as not voting: you either vote by voting, or you vote by staying home and tacitly doubling the value of some Diehard’s vote.