I am reposting, in their entirety, the ten articles I wrote that were published in SHIFT magazine (which is now on hiatus) between 2013 and 2015, since some of the links have changed and so that my blog contains the full text of these articles (useful for searches etc.) Thanks to SHIFT for the graphics (much better than my originals), and for publishing and editing my work.

image courtesy SHIFT Magazine; click on image to view full-size

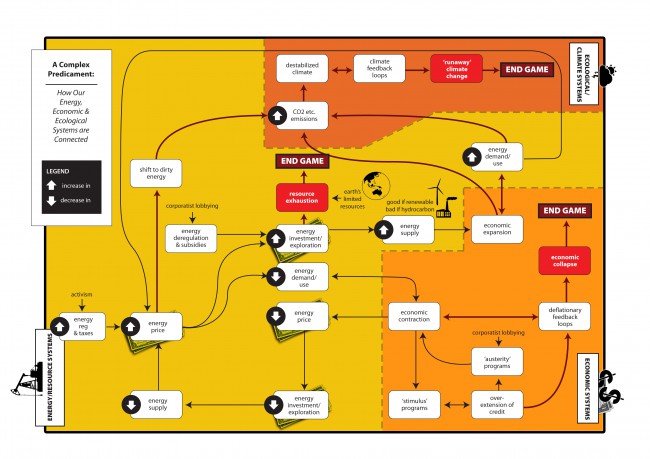

Part One: The Energy Predicament: Feedback loops, the Jevons Paradox, and the three End Games

It’s called the Jevons Paradox. It explains why increases in the efficiency of resource-consuming technologies tend to lead to an increase, rather than a decrease, in resource use. So, for example, it would explain that drivers of hybrid cars, rather than banking the savings on gasoline their vehicles provide, because of reductions in both cost and guilt, instead drive them further, sometimes even to the point they use more gasoline than they would have if they owned a non-hybrid.

In a broader sense, the Jevons Paradox is a way of explaining a puzzling behaviour of many complex systems. In essence, because we humans don’t really like to change, we will tend to ‘work around’ interventions in a system that were designed to bring about some desired change, so that the status quo of the system is maintained.

So, for example, Malcolm Gladwell’s research has discovered that you are actually safer driving in a convertible than in an SUV, because drivers of convertibles know the dangers of an accident and compensate by more careful and attentive driving, while SUV drivers, in the (mostly false) belief that their risk of and in an accident Is much lower, tend to drive more aggressively and less attentively, so they have significantly more accidents per mile (and in total face more injuries and deaths per mile as a result). (Don’t try to sell this logic to your insurance company, however.)

In addition, there are Jevons Paradoxes inherent in complex systems, that lead to undesired results that have nothing to do with deliberate human behaviour at all. For example, if we put a ‘carbon tax’ on fuels in the hope of reducing consumption and encouraging conservation, we may find that the reduced consumption will temporarily lower prices (as a result of lowered demand). But those lower prices will enable drivers to buy more gasoline for the same outlay, so they will fill their tanks more often — until that increased demand enables the gasoline vendors to raise their prices, completing the cycle.

And when the vendors can increase their prices, they can also economically justify exploring for and developing more costly, marginal hydrocarbon resources (fracking, deepwater oil, shale oil, tar sands). That increased supply starts another cycle, since more supply relative to demand tends to lower prices until the new supply can be fully sold. It’s all a delicate balance.

That is, until affordable oil (and other resources) run out entirely. The energy industry is fond of telling us there are centuries’ worth of potentially extractable hydrocarbons in the ground. But with the cost of extraction getting ever higher and the life of each new find getting ever shorter, the amount that can be extracted at a price consumers can afford is finite, and when it is used up we reach what Derrick Jensen calls EndGame.

This is where complex systems get especially tricky to explain, because they’re interrelated. What exactly is ‘a price consumers can afford’? This depends on our economic system, not our energy and resource systems. That system, as I will explain in Part Two of this series, is hurtling towards its own End Game. But the bottom line is that, as we come to realize that our unsustainable industrial growth economy is already hugely overextended (the debts we have incurred could only ever be repaid if we lived on a planet of infinite wealth and resources), the entire Ponzi scheme of our markets will collapse, and what ‘consumers can afford’ will plummet. End Game.

And all of this economic activity and resource development has pushed atmospheric CO2 and other global warming gases past what many climate scientists believe is the tipping point, so that ‘runaway’ climate change, and with it, massive droughts, desertification, fires, storms, water scarcity, species extinction, pandemics, infrastructure destruction and sea level rise are now, they say, inevitable in this century – a third End Game. (More about this system in Part Three below).

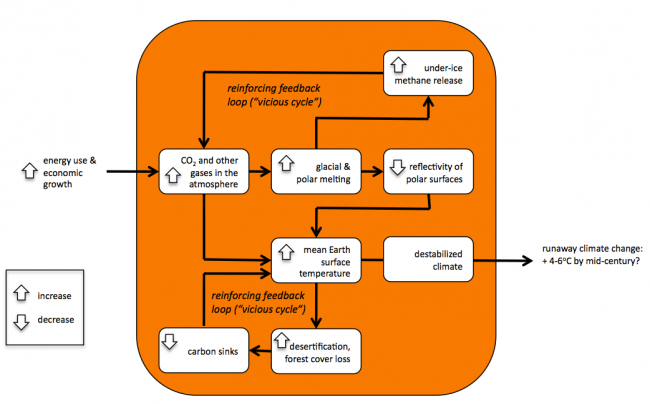

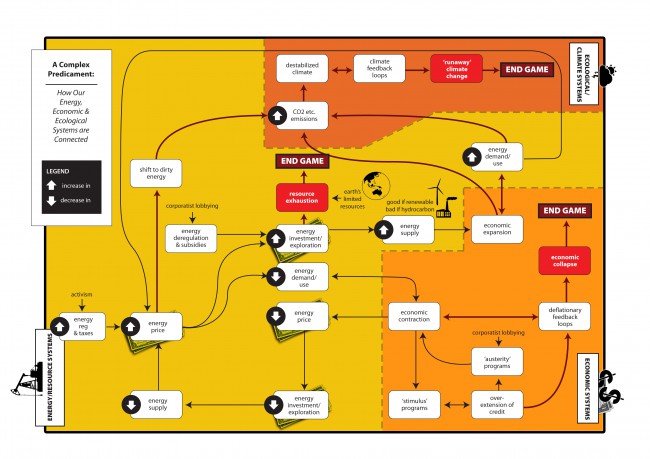

The very busy diagram on the next page of this article attempts to capture the most essential variables in these three systems – energy and resources, economy, and climate/ecology, and the three End Games that provide us with no futher possibility for intervention, and could well precipitate the end of our current globalized human civilization. It’s an expanded version of a chart in (Transition Movement co-founder) Rob Hopkins’ and (Post Carbon Institute Executive Director) Asher Miller’s excellent paper Climate After Growth.

It shows some of the major self-reinforcing and self-sustaining ‘feedback loops’ (e.g. how a destabilized climate characterized by rapid polar and glacial melting leads to increased methane release which in turn leads to more destabilized climate and more melting, with ‘runaway’ climate change as the result). It also shows the balancing ‘feedback loops’ that currently keep our energy/resource, economic and climate/ecological systems in ‘net stasis’ – not appreciably changing – for now.

But because of the three End Games, this stasis is not sustainable. We will, sooner or later, run out of economically affordable resources. Or we will run out of faith in the possibility of perpetual economic growth. Or we will face the realities of runaway climate change. All systems collapse when they fall out of stasis, and all civilizations end. The question is no longer how or whether we can prevent one or any of these End Games. It is, now, how do we prepare for the consequences of any or all three, as we enter the decades James Kunstler has called The Long Emergency, and how can we gauge whichever of the three is going to hit us first, and hardest.

And, once collapse comes, how we can learn from this astonishing life experience – from being at this pivotal point in human evolution – so that those living after the fall will be able to create sustainable, joyful societies (probably very localised, small scale societies that will, because they will be adapted to place, seem amazingly diverse to those of us living in our current homogeneous global human culture). And how we can help our descendants draw upon the best of pre-civilization (‘prehistoric’, since in our arrogance we presume that history only began with our civilization) ways of living, and also on the lessons of (civilization’s) history and the scientific and technological learning of today’s world, to create future human societies better than we could dream of.

But back to our complex energy/resource system chart. What this diagram explains is the futility of us trying to intervene politically or economically to bring about significant, sustained changes in the systems pushing us inexorably to the End Games. Carbon taxes, energy conservation and innovation, protests and blockades of dirty energy and resource exploitation are admirable and necessary, but they cannot hope to fundamentally change the status quo which will ultimately take us to resource exhaustion. Our entire civilization depends upon the ready availability of cheap resources that enable us to feed 7.5 billion humans today, and by mid-century 9.5 billion or more, most of whom will want to live, and hence consume resources, as we do today. If we run out – when we run out – we will find that such a horde cannot live on what we can produce with the energy of our hands and that of domesticated animals. (The average human can produce about 0.1 horsepower of energy in sustained manual labour; a car requires 150 hp or so, a train 4,000 hp per engine, an airplane 60,000 hp, a cargo ship 100,000 hp, a power plant 3,000,000 hp.)

I would like to believe, as Donella Meadows so eloquently explained in her Places to Intervene in a System paper, that a transformational human evolution, a way of fundamentally changing our whole global way of thinking and acting, our whole paradigm, is possible. As a student of history I don’t believe such changes happen, however, at least not on a large scale, not persistently, and not quickly. But even if I did believe, I would want to understand what we are facing if we are not successful in such a transformation, and how we might prepare for it.

I believe the key to doing that – to understanding what we are facing and what is possible – is through the use of story. That is how we have always learned and come to understand these things. I believe it is never too early to start to study and learn from the stories of previous civilizational and economic collapses – Ronald Wright’s A Short History of Progress, Jarod Diamond’s Collapse, and Pierre Berton’s The Great Depression are excellent starting points for this. And I believe it is the right time to start to write the story of the unfolding collapse of our current energy/resource, economic and climate/ecological systems, and hence the collapse, over the next few decades, of our own fragile civilization. Not as a story of apocalypse – the Mad Max scenario may make good cinema but a study of human history suggests it’s highly unlikely, and that collapse will occur more gradually and unevenly than we might expect, and our collective response to it will be gentler and more generous than we might imagine. We could probably learn much, too, from the homeless in our own communities, and from the people in the massive, sprawling slums of the third world, who are already living in cultures of collapse.

Through an understanding of how the complex systems of our world really work and how change happens, and through an appreciation of history and the telling of stories, I think we can move past denial and blame and start to move towards preparation for a future that will be unstable and unpredictable and much different from how many of us in affluent nations live today, but also exciting and satisfying and engaging and meaningful in a way our current culture does not provide. And that work can make us collectively resilient – not in the sense of ‘bouncing back’ to an unsustainable style of life, but in the sense of moving forward, courageously and joyfully, to a relocalized, communitarian style of life that is sustainable.

. . . . .

Part Two: The Economic Predicament: Should We Try to Precipitate Economic Collapse to Mitigate Runaway Climate Change?

David Holmgren, one of the founders of the Permaculture Movement, recently stirred up a firestorm of controversy with his Crash on Demand essay, suggesting that it would be useful for us to precipitate economic collapse as a means of mitigating both energy/resource exhaustion and runaway climate change. He summarizes:

My argument is essentially that radical, but achievable behaviour change from [being] dependent consumers to [becoming] self-reliant producers (by some relatively small minority of the global middle class) has a chance of stopping the juggernaut of consumer capitalism from driving the world over the climate change cliff. It may be a slim chance, but a better bet than current herculean efforts to get the elites to pull the right policy levers… My argument suggests this could happen by reducing capital enough to trigger a crash of the fragile global financial system.

This insight shows David’s appreciation of the nature of complex systems and the interrelationship between our global energy/resource, economic and ecological/climate systems.

As the chart at the top of this post shows, economic expansion is dependent on energy/resource supply, which is itself a function of the price, demand, investment and regulation variables I described in Part One, and in any case not endlessly sustainable even if the economy is able to support higher and higher extraction and development costs. A significant drop in energy/resource demand and use will precipitate a strong economic contraction (which has happened each time energy costs have moved significantly above the $100/bbl level).

But an even greater threat to the continuation of our current “grow or collapse” economy is the realization that current levels of debt in our economy are unsustainable. When that realization becomes impossible for markets to ignore, we will face the greatest depression in human history; no amount of ‘stimulus’ will be able to mitigate it, and there is no deus ex machina like war spending or the discovery of new cheap resources to get us out of it. More about that scenario, which even many economists can’t seem to comprehend, later in this article.

Back to David Holmgren’s proposal: The reactions to his article have been swift and sometimes harsh. Transition founder Rob Hopkins called David’s suggestions “a dangerous route to go down”. Rob remains firmly in denial about the inevitability of collapse, citing several optimistic ‘prosperity-without-growth’ economists in support of his belief that a concerted global effort by a broad coalition of knowledgeable, influential people can pull us out of the positive feedback loops currently leading us towards economic collapse (and indeed, End Games in all three major systems). I’ll look at that argument later in this article as well.

Dmitry Orlov essentially dismissed David’s argument as being inadequate to the task, but said that despite its futility, “Don’t let that stop you from trying because, regardless of results (if any) it’s a good thing to be trying to do.”

Nicole Foss, who David acknowledges as one of his influences, takes the opposite point of view to Rob’s. She has repeatedly argued that economic collapse will come soon in any case, with or without our attempts to undermine the current economic system (or for that matter, prolong it). She writes:

Once the financial system has the accident that is clearly coming, we will be looking at a substantial fall in societal complexity, but that fall in complexity will eliminate the possibility of engaging in such highly complex activities as fracking, horizontal drilling, exploiting the deep offshore or producing solar photovoltaic panels and inverters… [Because they will be completely unaffordable, none of these will ever be] a meaningful energy source.

In fact, some US states are already dealing with large-scale abandonment of quickly-exhausted fracking sites (with their commensurate ecological damage), and Shell recently announced it is abandoning its Arctic drilling programs because they are not economic, even at today’s $100+/bbl oil prices.

Nicole’s concern about David’s approach is that, since economic collapse is (she believes) inevitable and reasonably imminent anyway, taking an activist approach to opting out of the dominant economic system in order to accelerate that collapse runs the risk of stirring up virulent opposition from the rich and powerful, who could then demonize the entire transition/collapse preparation movement as anti-human, and ultimately shift the blame for the suffering that collapse will inevitably bring about to the “anti-growth” activists. She writes: “Inviting blame for an inevitable outcome seems somewhat reckless given the likelihood that many will be casting about for scapegoats.”

It is hard to explain why the Ponzi scheme that is our modern growth-dependent industrial economic system is unsustainable. It’s all really about faith in the value of money. And on the surface it seems to be holding: Governments and corporations, working together, have been able to suppress interest rates to near-zero levels for more than a decade now. The banks and institutional investors don’t need high interest rates when they can make greater profits through a combination of high user fees, arbitrage, hedged speculation, the sale of high-risk bundled ‘investments’ to unwary investors, usurious credit card and poor-credit interest rates, and foreclosures – and be bailed out by their government friends with taxpayer money when their investments go bad. They also lie about real rates of inflation and unemployment to suppress citizen dissatisfaction about the true state of the economy.

The Australian group Doing It Ourselves have put together a terrific 12-minute explanation of why and how our economic system is dependent on perpetually-accelerating growth and commensurate levels of debt – and on our faith that that is possible. That growth cannot continue because the remaining energy and resource supplies of our planet are becoming exponentially more expensive, and because the current staggering levels of debt – government, corporate, mortgages and other personal debt – can only be repaid as long as land and other prices keep going up, and incomes and borrowing capacity combined keeps rising to make the payments on those debts possible (and as long as interest rates remain very low). When this capacity peaks – and Nicole Foss and her Automatic Earth colleagues have eloquently argued it already has – buying freezes up, housing and investment values commensurately tumble, lost collateral means a plunge in available credit and an explosion of foreclosures, margin calls and debt repayment demands, falling sales, layoffs, and defaults, to the point that a positive-feedback-loop – a chronic deflationary spiral – kicks in. Japan has been suffering from this for two decades, and most Western nations are poised for a similar collapse – starting with the current fall into poverty of most of the middle class.

To get an idea of what this means, consider that the median household net worth in real currency in most Western nations is not significantly different from what it was in the 1940s, before the Ponzi scheme and the era of cheap money began – that is, a net worth essentially not much more than zero. All of the increase in apparent affluence – owning instead of renting, much larger average homes, two cars per family, more expensive ‘average’ cars, more clothes, more energy use, more stuff of every kind – has been borrowed, in the expectation that all these debts can and will be repaid. How? By whom? We dare not ask, because the answer is, nobody knows. We just keep hoping against hope that growth can continue forever, real incomes will rise, more efficiency will keep prices down and profits rising, more cheap energy will be found, our pension investments will keep rising in value, and someone will be willing to offer us more for our home than we paid for it, so we have more collateral to borrow even more against.

The Great Depression and the Recession of 2008 are just two indications of what happens when we realize this is not sustainable.

Advocates of “austerity” claim that theirs is a response to this unsustainability. But history has shown that austerity programs simply precipitate collapse faster, and place the entire burden for it on the poor, disadvantaged, ill and unemployed. That’s why progressives keep arguing for “stimulus” programs that crank up the illusory growth machine even more. But when the stimulus amounts to just printing of more money, most of which ends up in the pockets of the bankers and the already-rich, it is just an acceleration of the unsustainable, and will inevitably lead to even more spectacular collapse and greater suffering for all.

A number of “third options” to prevent economic collapse have been proffered. A transition to a steady-state economy, coupled with a large-scale re-localization to a world of more self-sufficient communities producing more themselves, living within their means, and hence more resilient to collapse, is the most popular of these options. If our economic system were not global, and was simple, with a few people controlling the whole economy, this might be feasible. But we live in a staggeringly complex, global economic system with no one in control, not even in individual countries with autocratic regimes. The “market” determines and affects our economic actions, and it is the product of all of our activities, and cannot be stewarded to some idealistic, better economic reality, even if we could agree on what that would look like. Billions of people in struggling nations want an economic life like that of the wealthy in Western nations, and they will act in accordance with that desire, regardless of what we, or their governments, seek to impose on them. It is our nature to attend to the needs of the moment, to seek short-term betterment for ourselves and those we love, and to hope that future generations will be able to do likewise, even when faced with growing evidence they will not.

Top-down reform of our economic system cannot succeed for the same reason top-down climate change prevention has not and will not succeed. No one is in control of large complex global systems. It is not the evil rich or evil corporations driving us to collapse. It is the ever-evolving systems in which we all participate and which no one influences enough to change direction in any coherent and sustained way that determine our trajectory to collapse. We want someone to blame, and even argue that “we are the system”, and we are all to blame, but we are not. The system will take its own course, as it always has. And all signs are that the courses our energy/resource, economic and ecological/climate systems are on, lead in each case to an End Game.

The economic collapse End Game has been vividly portrayed by Nicole in a ghastly list of “40 Ways to Lose Your Future”. No surprise that we don’t want to believe such collapse is now inevitable.

So back to the question that David Holmgren raises – about whether precipitating such a collapse before it happens anyway is (a) possible and (b) a good idea. I think it would be fair to say that David says ‘yes’ to both, Rob says ‘no’ to (b) and is afraid the answer is ‘yes’ to (a). Dmitry says ‘no’ to (a) but ‘yes’ to (b) anyway. And Nicole says ‘not really’ to (a) and hence ‘no’ to (b). I’d love to know what Charles Eisenstein would say. I suspect he’d agree with Eric Lindberg, who in a new article on the Historical Problem of Agency draws brilliantly on historical examples and the evolving narrative of human agency to these very tentative, thoughtful and honest conclusions:

What little agency humans might have [in complex systems] can only be achieved by understanding the underlying logic of history and by accepting the limits that logic imposes. When we realize this, we won’t try to grow the economy, develop the “developing world,” depend on genetically modified seeds and chemical fertilizers, look for a new source of fuel on Mars, and so on. Instead we will accept the coming contractions and adapt to them as best we can… Rob Hopkins is one of my heroes, but I read his response to Holmgren as a rather desperate attempt to maintain a course set by a narrative that is crumbling beneath us [as the runaway climate change narrative is eclipsing Transition’s peak oil narrative]…

Many of us understand the perils of revolution and violence, the simple fact that it has so infrequently worked. We understand, moreover, that the collapse of global economies, of civil society creates its own predictable violence. We understand that the result and consequences of any action that pursues radical, human designed change is neither controllable nor predictable. But at the same time, refraining from radical, potentially destructive, action is also a choice whose results are unpredictable and almost certainly dire. The stakes are as yet beyond comprehension. The question is no longer whether we can make history as we please, but whether “history” itself will continue to exist.

Eric concludes with a call for patience and tolerance and dialogue, and I think that’s a very sensible response to trying to cope with three intertwined complex global systems, all overextended to the breaking point and heading in disturbing directions very quickly. The economic system is the only one we may be able to intervene in (lunatic plans for geoengineering to prevent climate change aside), and the result of any intervention in our economic systems is doubtful and probably unpredictable. We can act, or we can, as Eric says, just accept what comes and adapt to it as best we can. The question of whether or not to try to precipitate economic collapse before it happens anyway, can only be answered in the context of your own personal (who you think you are) and cultural (who you think we are) narrative.

For many, the answer may depend on what we learn, in the coming months and years, about the accelerating melting of our planet’s polar regions, and the trajectory of runaway climate change. That’s the subject of Part Three of this series, below.

. . . . .

Part Three: The Ecological Predicament: If Runaway Climate Change is Now Inevitable, Is There Any Rational Response?

In his new book Requiem for a Species: Why We Resist the Truth About Climate Change, author Clive Hamilton writes:

It was only in September 2008, after reading a number of new books, reports and scientific papers, that I finally allowed myself to make the shift and admit that we simply are not going to act with anything like the urgency required… The climate crisis for the human species is now an existential one. On one level I felt relief: relief at finally admitting what my rational brain had been telling me; relief at no longer having to spend energy on false hopes; and relief at being able to let go of some anger at the politicians, business executives and climate sceptics who are largely responsible for delaying action against global warming until it became too late…

We [now] have no chance of preventing emissions rising well above a number of critical tipping points that will spark uncontrollable climate change. The Earth’s climate [will now] enter a chaotic era lasting thousands of years before natural processes eventually establish some sort of equilibrium. Whether human beings [will] still be a force on the planet, or even survive, is a moot point. One thing seems certain: there will be far fewer of us.

Climate scientists are of necessity experts in understanding complex systems, and over the past few years, when I’ve met with them, they’ve become increasingly pessimistic, to the point they are finding it difficult to reconcile what they have come to believe with what they are required, to keep their jobs and to keep audiences from walking out on them, to say publicly. Clive’s experience has been similar, and he says “Behind the facade of scientific detachment, the climate scientists themselves now evince a mood of barely suppressed panic. No one is willing to say publicly what the climate science is telling us: that we can no longer prevent global warming that will this century bring about a radically transformed world that is much more hostile to the survival and flourishing of life.”

Beyond the shock of coming to grips with this realization comes the challenge of trying to imagine what this “radically transformed world” will look like, and how we humans are going to respond to, and cope with it. What makes it even harder is appreciating that this will not be a sudden, overnight crisis, but what James Kunstler calls a “Long Emergency” that will unfold over decades or even centuries, in waves of varying intensity. And it will not be a temporary crisis, one we can bounce back from with courage and effort, but rather a permanent transformation of everything we now think of as our global civilized culture – the only way we know to live, the only way most of us can imagine living.

What I’m going to depict in this article is a scenario I am calling the Great Migration – the displacement and movement of billions of humans in search of a more hospitable place to live as runaway climate change makes the places most of us know and love as “home” unrecognizable and unlivable, and what will happen when those billions encounter billions of others whose home places are less affected, but not able to support even their current populations, let alone a massive influx of climate refugees.

But first, I want to return to the diagram I used earlier (see top of article), which shows the interrelationship between our economic, energy/resource, and ecological/climate systems, and how crises in one system can precipitate crises in the other two. Each of the three systems has reinforcing feedback loops that tend to accelerate disequilibrium (what we call “vicious cycles”), and other balancing feedback loops that tend to mitigate these accelerating changes and bring the system back into stasis.

As I said earlier, we are quickly running out of ways to intervene and keep these systems in balance, because our global energy/resource systems are predicated on the availability of unlimited, inexpensive resources, and our global economic systems are predicated on our capacity to generate unlimited and perpetual economic growth. Since neither system is sustainable, we are now beginning to spiral into reinforcing feedback loops that will take us to resource exhaustion and economic collapse, which will likely precipitate the end of our complex global civilization culture and a return to a much simpler, relocalized, low-tech and marginal human society (with, as Clive says, many fewer humans).

In this final part, I want to focus on our the reinforcing feedback loops in our ecological systems, shown at the top of this chart. There is now little doubt that we have passed the ‘tipping point’ to runaway climate change, and that it will now radically alter the face of our planet in this century and for millennia to come, and will do so even if we were to stop all human activity tomorrow.

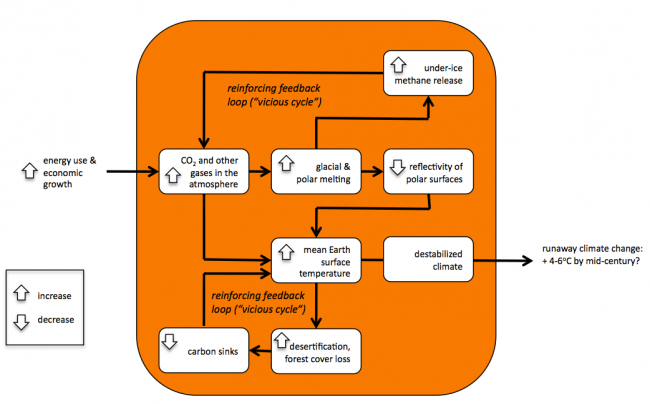

Here’s a closer look at the “climate feedback loops” box in the chart above, showing what climate scientists say is now happening to our atmosphere:

Because we were, until recently, looking at these changes in our atmosphere as linear phenomena, and ignoring (or being unaware of) the reinforcing feedback loops, we were extremely optimistic about our ability to forestall climate change through coordinated human action. Now we realize that some of the natural consequences of atmospheric warming (methane release from the arctic, more heat absorption as ice cover disappears, desertification, forest cover loss and other changes reducing natural “carbon capture” sinks, and other phenomena in the oceans we are just beginning to understand) actually reinforce and accelerate warming. As a result, some recent studies now predict a median surface temperature increase of 4oC or more as soon as mid-century, and 8oC or more by end-of-century, regardless of what actions humans take to mitigate the accelerating rise. This is far more than was predicted even just a year ago.

These scientists also agree that this quantum of change, which is comparable to the change that happened when the Earth last slid into an ‘ice age’ (though in the opposite temperature direction), is catastrophic – it will render most of the planet uninhabitable to humans without using prohibitively expensive prosthetic technologies.

Here’s what “runaway climate change” means, according to various scenarios described recently by climate scientists:

- the uncontrollable burning of most of the world’s remaining tropical, subtropical and temperate forests due to latent heat

- the prevalence of desertification, disappearance of glacial melt, coastal flooding, massive water shortages and/or endemic high rates of heat-related deaths in many of the world’s temperate zones

- an ice-free world, with a commensurate rise, sooner or later, of 50-70m in sea levels

- unprecedented and chronic floods, storms and monsoons

- the death of almost all ocean life

- large-scale collapse and abandonment of aging physical and technology infrastructure not designed for such extreme and frequent weather events

- massive numbers of climate change refugees, migrating (mostly north) thousands of miles in search of lands that are still habitable and arable

How might humans respond in the face of such change, transforming our planet over the course of the next few decades?

Here’s the scenario I envision we might see, based on my study of the collapse of past cultures, on the human movements that occurred in response to ‘ice ages’, and on what I have learned about human response to crisis from studying great depressions, famines and other massive cultural dislocations.

- Pulling together in times of crisis, and experimentation with new ways of living: I believe the response of most people to climate and other crises will, rather than panic, violence or selfishness, be more nuanced, peaceful and collaborative. The Long Emergency will give us the opportunity to try out a variety of pragmatic responses before we need to cope with the more extreme consequences of climate change.

- Massive dislocation: Just as during the latest ‘ice age’ a large proportion of the planet’s people would have been forced to migrate towards equatorial areas of the planet, climate change will require the people now living in tropical areas (which will be scorched out), and in many desertified and parched, or inundated coastal subtropical and temperate areas (much of the Western US and Canada, much of Australia, all of Southern Europe and the Middle East, much of Southeast Asia and most of Mexico and Central America) to migrate north (and/or to higher ground inland). At least two billion people live in these areas now.

- A Great Migration: What we will see, I think, is a gradual swell of people, a Great Migration over a few decades fleeing famine, thirst and disease. Those who migrate may encounter friction from those in more temperate areas struggling with resource exhaustion, economic collapse and less severe climate crises, who will not welcome climate refugees adding to their population and resource pressures. But many of these xenophobes will then be forced to join the Great Migration further north as the habitable area of the planet continues to shrink.

- Squatters, encampments and a “baby bust”: There will be no money to build new infrastructure for these billions of new refugees, so most of them, I predict, will live either as nomads, scrounging what they can from abandoned land (monoculture farms, bankrupt, deserted suburbs etc.), or in massive settlement camps, reliant on food handouts. Birth rates among these billions will plummet as hopelessness and malnutrition become endemic, so most of the mid-century fall in human population will be the result of rapidly falling birth rates rather than rising death rates.

- Emptied cities, relocalized communities, and the collapse of large institutions: For those fortunate enough to live in sub-polar and boreal areas with adequate precipitation, or in cooler temperate regions where soils have not been seriously depleted and where urbanization is modest (high density urban areas and suburbs will fare badly when the economy collapses and essential resources become unaffordable), will likely fare relatively well – they’ll be too far away for most climate refugees to reach, and not as seriously affected by the worst effects of climate change. For them, economic collapse will mean a dramatic relocalization of society – collapse of national and regional governments, large corporations, international trade and markets, leading to devolved authority and responsibility to communities, with enough time to relearn the essential skills of living in community.

- Most human infrastructure abandoned: David Korowicz, an economist and complexity expert with the Irish sustainability think-tank Feasta, explains that much of our social fabric is based on large-scale ubiquitous infrastructure, which will have to be abandoned due to economic collapse and the Great Migration. In his study “On the Cusp of Collapse” [http://www.feasta.org/2011/10/08/on-the-cusp-of-collapse-complexity-energy-and-the-globalised-economy/] he writes “We are deeply dependent on the grid, IT and communications, transport, water and sewage, and banking infrastructure… amongst the most technologically complex and expensive products in our civilisation… This [ever-deteriorating] infrastructure requires continuous inputs for maintenance and repair [and] specialised components that depend upon very diverse and extensive supply-chains.” The abandonment of this infrastructure (we won’t be able to maintain it or take it with us as we move) will of necessity require a shift to a much simpler, subsistence lifestyle.

- Food scarcity and the need to shift to organic, sustainable permaculture: The complexity and interdependence of our systems will introduce other challenges as infrastructure essential to these systems is abandoned. David Korowicz explains: “Global food producers are already straining to meet rising demand against the stresses of soil degradation, water shortages, over-fishing and the burgeoning effects of climate change… 7-10 calories of fossil-fuel energy go into every one calorie of food energy we consume… Without nitrogen fertiliser, produced from natural gas, no more than 48% of today’s population could be fed [even] at the inadequate 1900 level. No country is self-sufficient in food production today. The fragility of the global food production system will be exposed by a decline in oil and other energy production. It is not just the more direct energy inputs, such as diesel, that will be affected, but fertilisers, pesticides, seeds, and spares for machinery and transport. The failing operational fabric may mean there is no electricity for refrigeration, for example… A major financial collapse would not just cut actual food production, but could result in food left rotting in the fields [and consequent famines].” As these massive food systems collapse, relocalized, organic, more resilient and flexible permaculture systems will replace them.

The above scenario – a Great Migration, a collapse of human numbers, economic and energy systems and infrastructure, and a relatively peaceful shift to a radically simpler and relocalized way of living — is only a guess, of course, one of a million possible outcomes. We can’t know how system collapse will play out. But those who have been paying attention know that business, and life, “as usual” will not be possible much longer, especially for our children and descendants.

So how, and when, do we prepare for such a future? How do we give up trying to perpetuate the unsustainable and instead begin to prepare for failure?

In his article “Tipping Point”, David Korowicz says:

“Part of the preparation is in the acknowledgement of our predicament, that we recognise it when we see it. That as systems fail, we spend our efforts on positive change and adaption, rather than finding scapegoats or letting anger and loss drive the cannibalisation of our social fabric… Those who, through fear or avarice, try and insulate themselves from the impacts by disproportionate hoarding or land grabs will imperil not only their community’s security and wellbeing, but their own. This will be a time when we really will need the cooperation and support of others.”

If we look at the history of peoples who successfully made the transition from a collapsing civilization to a sustainable, subsistence post-civilization culture, we can identify four viable strategies:

- Relearn essential skills, knowledge and capacities that have been lost as our culture has become dependent on complexity, centralization, hierarchy, imports and unsustainable infrastructure. These include technical skills, “soft” skills (like facilitation, conflict resolution and mentoring), and knowledge – including knowledge of place and self-knowledge.

- Learn to create and build community: Practice the arts of working, sharing, collaborating and cooperating with those in your immediate physical neighbourhood. Collapse will force us to make things work at the community level, together.

- Heal ourselves and each other: Understand and appreciate the damage that the stress of our fiercely competitive, scarcity-creating, horrifically unequal and morally agnostic culture has done to us, physically and psychologically, and work to help each other recover from that damage.

- Live an exemplary, joyful life: Most people will not be swayed by impassioned arguments from strangers about “what we need to do now”. But they will appreciate, and consider emulating, those who live and act, every day, in ways that seem inspiring, conscious, sensible, and admirable.

As the philosopher John Gray has written, it is human nature to be preoccupied with the needs of the moment, and to put off thinking about or acting on issues that, however important, do not seem urgent. Most of us are therefore unlikely to change our behaviour until it is too late, and as a result the transition – through a cascading series of existential crises to an unimaginably different way of life – will be challenging, unpracticed, unprepared for, and probably quite chaotic. As Buddha put it: “The problem is that we think we have time.”

As long as we continue to mistake our complex predicament for a merely complicated problem with “solutions” – believing blindly in new leadership, new technology, new consciousness, or salvation from a higher authority – we will continue to live nostalgic, unsustainable, irrationally hopeful and hopelessly idealistic lives.

Some of us will have to do better, and be ready for whatever is to come, as unpredictable and harrowing as that may be, and show others how to adapt and live differently. We will have to do this with the knowledge that collapse is no stranger to this fragile planet, and with the awareness that we’ll inevitably make some big mistakes in the struggle to create new cultures that are viable in a strange and turbulent new world. And with the belief that beyond that struggle is a world unimaginably different from industrial civilization, a world of real peace, equality, connection, freedom and joy.

The Great Migration, and beyond it the new and smaller role of our species aboard Spaceship Earth, is our new human story. It’s not too early to start writing it, and telling it to everyone we know.

Ren stood in the middle of the stream, tossing his line into the water, not looking at all like a real fisher. He wore only a brief bathing suit, revealing the huge tattoo of a wolf howling at the moon that covered the whole back half of his body.

Ren stood in the middle of the stream, tossing his line into the water, not looking at all like a real fisher. He wore only a brief bathing suit, revealing the huge tattoo of a wolf howling at the moon that covered the whole back half of his body.