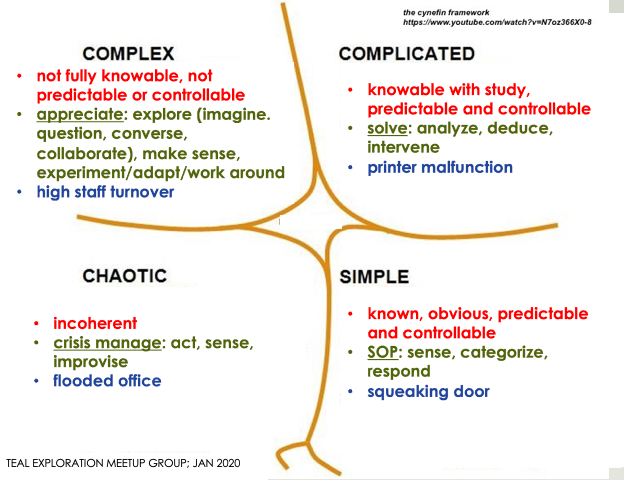

I recently did a mini introductory workshop on complexity and systems thinking, describing the difference between complicated and complex systems using my friend Dave Snowden’s Cynefin Framework (characteristics of each type of system in red; approaches in green; small business example in blue):

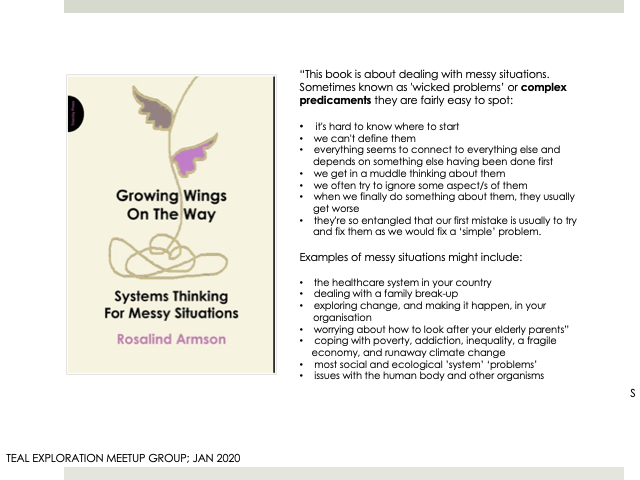

I then introduced the systems thinking methodology of Dr Rosalind Armson:

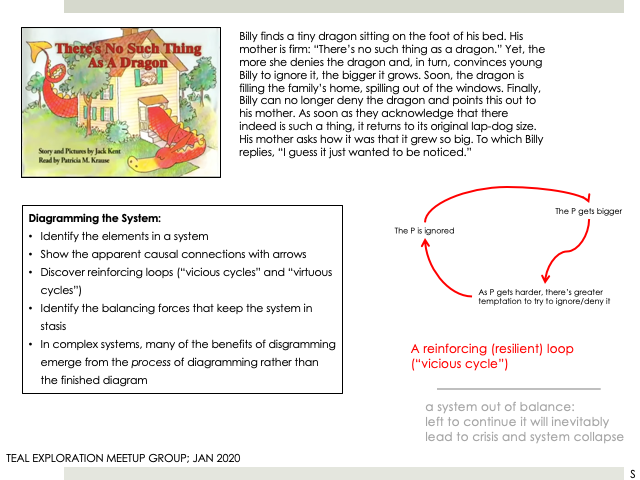

and then introduced Dr Armson’s systems diagramming methodology and terminology, using a children’s story as a model (the ‘dragon’ in the story is an excellent metaphor for just about every complex predicament one can encounter; just replace ‘dragon’ with ‘alcoholism’ or ‘child abuse’ or ‘neglect’, or replace the ‘house’ with ‘Earth’ and the ‘dragon’ with ‘global warming’ or ‘systemic poverty’ and it’s pretty much the same ‘story’ — so I’ve used the letter ‘P’ as the symbol for whatever the particular predicament being explored is):

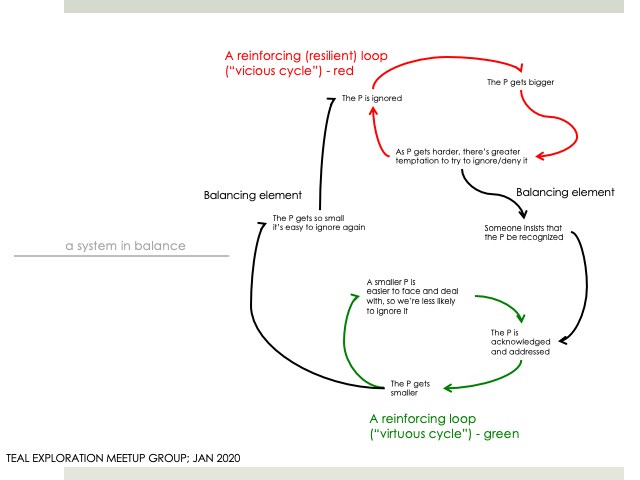

and then we charted that story:

Applying the same chart to describe, say an effective vs ineffective national housing, health or education system, the virtuous circle would be something like Finland’s (high tax rates to finance government programs, primary mandate to meet the common good, large ownership of and investment in public buildings/institutions/ infrastructure, and public benefits such as an educated and healthy citizenry and a low crime rate). [Thanks to Tree Bressen for the link]. The vicious cycle would be the one most of us are familiar with (constant downward pressure on tax rates, primary mandate of enriching private shareholders and landholders, institutions/land/ infrastructure largely or mostly privatized, constant pressure to cut services to offset reduced tax revenues, and commensurate high rates of homelessness and crime and low rates of physical and mental health and affordable housing).

The balancing elements that take a nation from the virtuous to the vicious cycle might be factors like the demand by a few very rich and powerful people to slash national tax rates (or else the rich will decamp to a lower-tax-regime state). This is what happened in Thatcher’s UK for example.

The balancing element that takes a nation from the vicious cycle to the virtuous cycle might be something like the Sanders/Warren proposals for universal health care in the US funded by a substantial tax increase to the richest 1%. I say might because the situation is extremely complex; we can’t know for sure we’ve factored in even the most important variables, and what elements might come into play to keep the vicious cycle intact. This is why there is generally (and justifiably) a lot of nervous, knee-jerk opposition to any radical change, and why self-reinforcing feedback loops are so hard to escape from.

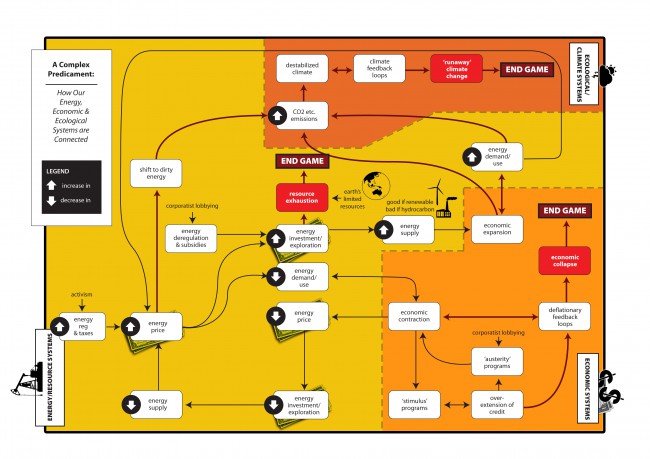

Of course, real world complex systems (and their charts) are much more involved than this, with many more elements and cycles, and come with the sobering acknowledgement that (i) we can never know all of the elements at work, (ii) while we can guess at the cause/effect relationships in how we draw the arrows, we may later be surprised to find that they’re merely correlations and possibly not causal (or predictive) at all, and (iii) while diagramming what we think we know about complex systems helps us understand what is going on much better, the ‘answer’ (eg the balancing element that moves the system from a vicious to a virtuous self-reinforcing loop) will never simply ‘drop out’ (be deductively obvious) the way it may in merely complicated systems like a malfunctioning automobile.

The diagramming process also challenges our assumptions and judgements: If one of the supposed elements is ‘human greed’ or ‘stupidity’ (or some convenient ‘evil’ enemy), a more thorough study of what’s really happening is more likely to discover that what is happening, is happening for a perfectly justifiable and understandable (and not readily correctable) reason. As I assert in Pollard’s Law of Complexity:

Things are the way they are for a reason. To change something, it helps to know that reason. If that reason is complex, success at truly changing it is unlikely, and adapting to it is probably a better strategy. Complex systems evolve to self-sustain and resist reform until they finally collapse. That is just how they work.

Blaming someone for a system caught in a vicious cycle is usually simplistic and unhelpful, and changing governments (or CEOs) is rarely sufficient to escape the cycle. Assuming “we’re all doing our best” is generally a better approach.

This is why we (as a species) loathe complexity. We want things to be easy, binary, rationally deducible. We want to believe we have the control and power to make things better.

So having diagrammed (to the extent we can) a complex system, what is required to determine what (if anything) might be an appropriate action or reaction, is generally a collective intelligence process, involving a diversity of as many knowledgeable, open-minded, creative people as possible.

That brings me to the subject of this article, which is: What makes for an optimal collective intelligence gathering process?

There are two competing points of view on this, and I think it’s essential that they be reconciled if we have any hope of achieving a useful consensus:

- Evidence-based approach: Collect lots of data, look for broad patterns, deduce appropriate interventions

- Story/anecdote approach: Listen to lots of stories, synthesize understanding, infer appropriate interventions

When it comes to, for example, human illnesses, ‘big’ medicine prefers to do lots of evidence-gathering research, find correlations, and prescribe therapies that seem to work in the preponderance of cases. It fails to conduct longer-term studies because they delay interventions too long and cost too much, it can easily fall prey to bogus research paid for by medicine and food manufacturers (and is inevitably shy on evidence of the efficacy of non-money-making treatments like better diet), and it ignores the astonishing and largely unfathomable complexity of the human body and the utter uniqueness of each individual body’s reactions.

Some medicine, on the other hand, is based on personal experience, stories from individual patients, and conviction that what works in some specific well-known cases may work well in the general populace. It is often based on thin and sometimes highly-subjective data, and also is prone to biased and bogus self-interested research, and also inevitably remains largely ignorant of the complexity of the human body and the uniqueness of each body’s reactions.

Of course, most practitioners will draw to some extent on both approaches. For example, Dave Snowden and others have developed tools that collect large numbers of stories and seek out useful patterns in them. Another example is Michael Greger’s nutritionfacts.org, which filters out biased and fundamentally-flawed nutritional ‘research’ paid for by vested interests, adds in the (small sample size, since these studies aren’t profitable to anyone and hence are underfunded) research that has been done showing strong correlation between specific whole food consumption and health and longevity, and suggests how each of us, factoring in knowledge of our own personal bodies, might make use of the inferences of that body of evidence.

But the current complicated medical system in most countries is simply incapable of producing anywhere near optimal outcomes for the very complex problems of human health.

What might work better? Clearly, a system that informed patients of appropriate illness prevention processes (diet, exercise, sleep, selective supplements), and encouraged and enabled patients to take personal responsibility for monitoring their personal health and the efficacy of various therapies for them personally, would almost certainly extend most people’s lives by years and their ailment-free lives by even more years, and that would have astonishing effects on almost every aspect of our modern society. But to change to such a system would likely involve the dismantling of the capitalist basis that underpins it, and an almost unfathomable change in public perception of the value of (paying for) public services. We’re caught in the vicious cycle of our dysfunctional and unsustainable health (and related social, educational, economic, and technological) systems.

Whether it could be done before the systems collapse is the key question. Once systems collapse, there’s a temptation to try to rebuild them (which almost always fails since the dysfunctional dynamics remain). And then something different is tried, until, for better or worse, a new system is created that has enough stability to be sustainable.

Now that the massive collapse of our stable climate, industrial growth economy, and other global systems appears increasingly imminent, there is some thought going into trying to answer this question. If there were a concerted effort by a large number of disinterested (unbiased but passionate), attentive, non-judgemental, dedicated, critical-thinking, coordinated, cooperative, collaborative, informed thinkers to collectively evolve a set of interventions that might either (a) mitigate collapse enough to reform the system so that it is once again sustainable, or (b) replace the existing dysfunctional system promptly once collapse occurs so as to produce the minimal amount of suffering to the human and more-than-human world, would it get enough attention to be implemented, or would it just be ignored as another radical ‘impracticable’ egghead ‘solution’?

A number of recent initiatives have broached this question. In the 1990s, David Bohm suggested a form of dialogue that might facilitate just such collaboration. One of the objectives of The Wisdom of Crowds was to identify how and when large collectives produce better answers than any small group, no matter how competent, could hope to produce.

More recently, Daniel Schmactenberger has spoken about the need for us to hone and practice our critical thinking, conversational and collaborative capacities and apply them, first to listening to and understanding those with whom we disagree (no one is to blame; we’re all doing our best; everyone has a piece of the truth; people believe what they do for a good reason), and then to engaging in earnest, purposeful dialectics to start to appreciate some potentially useful approaches to complex predicaments. Daniel also suggests some personal vows going into such deliberations: fierce dedication to knowing the truth, not turning away when that truth is unbearable, staying open-minded and caring and equanimous, constantly challenging everything one believes, and having the courage to seek out approaches and ideas even when you’re so far ahead of the curve there is no one who can guide you.

All of these initiatives eschew debate and rhetoric and resolve to dispense with misunderstandings, untruths, untruthfulness, and bias (conscious and unconscious) in our search for ideas and approaches to deal with the immense challenges we now face.

If you believe, as I do (at least for the moment) that there is no such thing as free will, what is the point of aspiring to do any of this? As I suggested in my earlier article, I don’t think we have any choice. Those of us with this turn of mind just have to look for approaches that might work, despite the apparent impossibility of any such approaches being found.

image courtesy SHIFT Magazine; click on image to view full-size

We have been in situations that were seemingly ‘impossible’ before, and when we reached the tipping point where staying with the existing system was obviously no longer an option, we introduced radical changes. This happened with the New Deal and similar programs worldwide that essentially suspended much of the capitalist system to deal with the 1930s economic emergency. It happened with the collective response to German atrocities in what became world war two, which required a near-global massive sacrifice of a beloved way of life to deal with an existential threat. It’s sometimes easy to forget how quickly and radically we’re somehow able to shift gears when we know we have no choice.

If we have no free will, neither do we have any choice about what we do, or fail to do, as economic and ecological collapse deepens. It will be interesting to see whether an increasing number of us have no choice but to start exploring collective intelligence gathering processes, à la Bohm or Schmactenberger, to try to mitigate and be ready to replace collapsed systems. It seems, we have to try.

The Schmactenberger interview you linked to before (which I found independently) interested me quite a bit, but I admit to eventually tiring of it, considering its abstract, theoretical consideration of a reality always receding before us — an endless treadmill of Sisyphean futility. Like you, I consider attempts at sense-making inevitable but for different reasons. You end many of your posts with a nod to nonduality and lack of free will, whereas my sense of having no choice derives more from ethical obligation, which I daresay not everyone shares. I also admit to make frequent nods in my own blog posts to collapse of human and ecological systems. Maybe these approaches are closer together than I think.