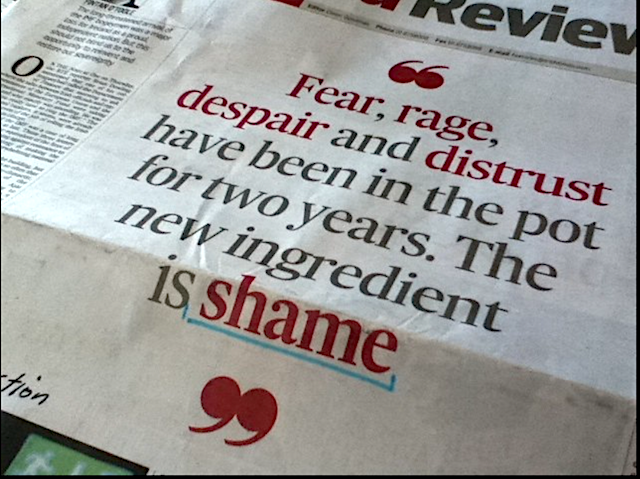

photo of an Irish newspaper headline, by Underway in Ireland on flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Tell the people they are safe now

Hunger stopped him, he lies still in his cell.

Death has gagged his accusations.

We are free now, we can kill now,

We can hate now, now we can end the world.

We’re not guilty, he was crazy

And it’s been going on for ten thousand years!

— Peter Yarrow, The Great Mandala

Two of my most popular posts have been about the culture of fear that underlies much of what is happening in our modern world, and much of our collective psychological malaise. In the earlier article I wrote:

You would think that compared to those who grew up in war zones or during great depressions, today’s citizens of affluent nations would have it easy, but we don’t — even in past times of crisis there was almost always an underlying social cohesiveness that served as a bedrock to enable us to “keep calm and carry on” until the horror ended. And there was a belief that it would end.

Not so today. I think there’s a growing, instinctive, subconscious realization that our civilization is nearing End Game, that “there is no future”, and I see a growing sense of anomie that disengages us from each other and makes us feel “hopeless”. Domesticated creatures like us, saddled with ‘selves’ and trapped between an often-troubled past and an apparently globally ghastly future, desperately need hope to function coherently. We need to believe, as past generations have, that with hard work and determination we can make the world better for their children than it was for them. Who now still harbours such delusions?…

Our stories now foresee no recovery, no long-term improvement, no stability, no hope. No future. When people are suffering and they have no hope, they tend, I think, to be driven instead by fear. And we are all suffering. We are living in the world TS Eliot foresaw when he wrote “the whole earth is our hospital”.

In my second article I identified the three main fears that I think now drive us:

Humans are of necessity a social species: We are physically quite weak and vulnerable (compared to most other creatures), and lacking much inherent self-sufficiency and autonomy (we spend a long period in the womb and another long post-natal learning period). Loners do not fare well inside or outside human cultures. We rely on each other to survive and to thrive, so it is not surprising that evolutionarily successful cultures are built on love and willing collaboration…

While most healthy tribes’ and communities’ collective effort is oriented to meeting each other’s physical and emotional needs, such cultures are also driven, at least secondarily, by certain healthy fears. I have written elsewhere that I think there are three primary fears in every human culture:

-

- fear of suffering (our own and loved ones’), and the related fears of the unknown and potentially-traumatizing surprises;

- fear of not being in control (helplessness, disability, incapacity, dependence, being trapped) and the related fears of social anxiety, lack of autonomy, lack of essential knowledge, and of “not having enough” (uncontrollable scarcities, including time); and

- fear of failure and inadequacy (ridicule, incompetence, letting oneself and others down).

These fears are evolutionarily healthy because they drive behaviour which is cautious, sensitive, self-responsible, and responsible to the other members of the community.

But when they remain unresolved, and become chronic, and are exaggerated and fed by those hoping to capitalize on such fear, we become deranged, and start to become like those endlessly confined and terrorized in prisons, refugee and slave labour camps, factory farms, laboratories, and other institutions of fear and suffering.

Something struck me when I was re-reading Zadie Smith’s 2014 article on the “new normal”, when she wrote:

Belief usually has an emotional component; it’s desire, disguised. Of course, on the part of our leaders much of the politicization is cynical bad faith, and economically motivated, but down here on the ground, the desire for innocence is what’s driving us. For both “sides” are full of guilt, full of self-disgust—what Martin Amis once called “species shame”—and we project it outward. This is what fuels the petty fury of our debates, even in the midst of crisis.

I realized that the second and third “fears” in my bulleted list above are precisely what give rise to this “species shame”. Our reaction to feeling this shame is often initially one of anger — feeling shameful is an horrific experience, one that makes us want to lash out at someone, anyone, we can hold accountable for making us feel this way — governments, leaders, “others’ of all stripes. Because if we can’t blame our shame on “others”, our propensity is to blame ourselves, and, when there’s actually nothing we can do or could have done differently, that self-blame is absolutely toxic.

What the never-ending barrage of crises of the 21st century — almost assuredly civilization’s last — has done is to constantly tear open what Martin Amis called the “unhealed wounds” of trauma, guilt, grief, fear and shame that all of us, by one means or another, have suffered.

So what is it exactly we are ashamed of?

I think it depends who and where you are. Our politicians, corporatists, PR people and marketers have found it quite easy and convenient to invoke in the oppressed castes a sense of responsibility for their own ‘failures’ — for their physical and mental illnesses, their poverty, their lack of education and knowledge, and their failure to ‘succeed’ at becoming rich, famous and/or loved. So I think a lot of the shame of people feeling (or being told) they’re not good enough, has its roots in this encouraged self-blame. When that self-shame gets refocused on others “to blame”, we see riots and revolutions. But they rarely accomplish much of anything, and being left with no “other” to blame we revert to self-blame, and to shame.

For many idealists, the ongoing collapse of industrial civilization in the face of everything we were brought up to believe was true, and possible, is more important for it being ‘human-caused’ than for it being an existential threat to life on the planet. If it’s human-caused, we have reason to feel shame, whereas if it’s not, it’s up to the gods and all we can be expected to do is our best. If we can’t blame someone, anyone, even ourselves, then it follows, we’ve been taught, that nothing can be done. We trade the shame of responsibility for the shame of helplessness. Surely we can do better than this!, we tell ourselves.

The things we have been most upset about in recent years (eg the conditions in prisons and factory farms, our inability to defeat or even agree on how to defeat this pandemic, the decline of democracy, the soaring levels of inequality, the endless abuses stemming from casteism, racism and misogyny) have often aroused the greatest ire because they have a scent of “you (or we) should be ashamed of yourselves (or ourselves)”, an accusation that is so confronting and so damning it frequently provokes violence in response. Any reaction, for most, is preferable to the shame of admitting failure, incompetence, ignorance, or “letting everyone down”.

You probably know me well enough to know that I think such reactions stem from the long-held and -reinforced belief that we each have separate ‘selves’ in control of these bodies we presume to inhabit. Give up the belief in free will, control, and separation, and there is simply nothing left to be ashamed about. We are all doing our best, the only thing we can do, and no one is to blame.

Of course, you may be thinking, I’m merely displacing individual and collective blame, shifting to ‘blaming’ our ‘selves’, and, by further alleging that our sense of free will, control, separation, responsibility and ‘selfhood’ is illusory, a mental misunderstanding in our struggling brains, I have simply sidestepped the question of who’s to blame and hence who should feel ashamed, and what should therefore be done to/by the guilty. The ‘dog that ate my homework’ doesn’t actually exist. To blame our imaginary ‘selves’, I’ve been told, is as intellectually dishonest and self-deceiving as blaming other abstract, practicably unassailable enemies like ‘terrorism’, ‘Russia’, ‘China’, ‘the powers that be’. Or other ‘invisible demons’.

They may be right, but as much as I’m inclined to doubt ‘pat’ answers to challenging problems (including that ‘there is no answer’), I don’t think I’m ‘blaming’ our ‘selves’. We’re all continually healing, and all continually having those “unhealed wounds” torn open again. What we do is all we can do, the only way our selves can make sense of things, even when we ‘know’ in some subconscious way that they don’t actually make sense.

Does that lessen my own, frequently-felt shame? Not one iota. Although I admit I have only recently been willing to countenance that it is shame, every bit as much as fear, that powers my self-blame and sometimes even self-loathing. Whenever fear arises, it is almost immediately followed by shame. How could I possibly fear that; there’s nothing there to be afraid of. How could I be so stupid, so weak, so demanding, so incapable, so dependent, so ridiculous, so disappointing to others who I care about?

But that is my conditioning. I’m just the dog in the stands barking fruitlessly at the misbehaving actor onstage, my namesake, my ‘person’. For all my barking, I’m helpless to correct his idiocy. Shame on both of us. Ahwoooooo!

> But that is my conditioning. I’m just the dog in the stands barking fruitlessly at the misbehaving actor onstage, my namesake, my ‘person’. For all my barking, I’m helpless to correct his idiocy. Shame on both of us. Ahwoooooo!

ミ●﹏☉ミ