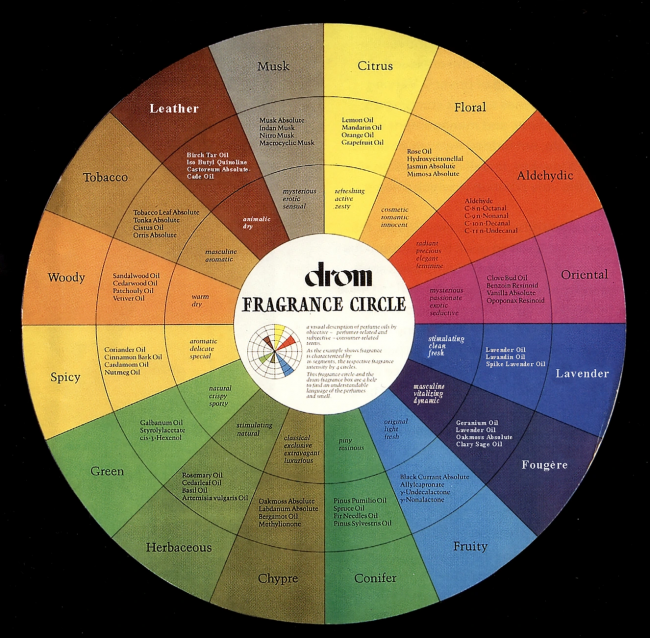

fragrance wheel from drom, from ‘top notes’ (citrus) around to ‘bass notes’ (musk), one of many different attempts to taxonomize the scents used in perfumery

When I was young, my emotions and my sense of place and time were quite powerfully connected with my sense of smell. I remember the smell of different places: When, as a young boy, I visited the UK, I could distinguish many of its places by their smell, even with my eyes closed. I am told that, in those days, England used a lot of diesel fuel compared to Canada, and Wales of course produced a lot of coal, and that concentration of carbons might have signalled to my ‘palette’ of remembered smells to tell me where we were. Though I also noted that the skies in the three countries, and different places within them, also had unique shades of blue, so it may be that my sense of place was triangulated somewhat by those clues as well.

On my last visit to England and Wales, the different smells were immediately recognizable, as were the different shades of blue in the sky. And smelling them and seeing them immediately brought back ‘forgotten’ memories of other times I had been in those places, a phenomenon known as simultaneity. Of course, I couldn’t tell you how the smells were different, or how the skies were different in ‘blueness’. I just knew, in a deeply subconscious way, where I was, and what it was like when I had been there before.

How little we know about our bodies (as the constant proliferation of new and old ‘incurable’ diseases reminds us)! And when it comes to our senses, we seem to know almost nothing. We don’t even have a proper vocabulary to describe these smells — we know that we can distinguish about 1500 different ‘distinct’ smells (whatever that means), as well as millions or more combinations of these smells, but there is no agreed-upon taxonomy for them. Compounding our ignorance, we know that our senses of smell and taste are largely synaesthetic — for example, when our nose is plugged, we can hardly distinguish tastes at all.

Our sense of smell develops before birth, as it’s needed to be able to distinguish our mother and her nourishment even without visual clues.

There is substantial evidence that our capacity to discern smells is one that, like our imaginations, can be lost, from lack of practice using it, and regained with renewed practice. Just as wine-tasters learn about the qualities of different vintages through practice, so too can we, by paying attention, become much more attuned to the scents all around us, what they signify, and how profoundly our emotions are influenced by them.

We might even be able to ‘condition’ our subconscious to improve our mood, awareness, and capacities, simply by exposing them to certain smells.

The olfactory ‘sciences’ are, like medicine and other sciences of the body, still pretty medieval. Fragrance ‘wheels’ have been developed, but they are mostly to guide those in the business how to replicate scents and sell them to the public, and there is little agreement among them. There is no accepted ‘language’ or ‘colour wheel’ of smells in any of Earth’s major cultures.

If you’ve read Jitterbug Perfume you know that commercially successful perfumes and scented candles have a balance and synergy of three types of ‘notes’, from fleeting ‘top notes’ to grounding, enduring ‘bass notes’, and that there is a broad trans-national consensus on which scents are particularly pleasant (vanilla, lavender and jasmine are the perennial ‘top 3’ in most countries), and which are particularly unpleasant (sulphur consistently ranks last). But beyond that, which scents are preferred, and particularly which ‘whole-is-more-than-the-sum-of-the-parts’ blends of scents are preferred, varies wildly from person to person, and those preferences, much like our taste in music, are deeply affected by what past events (and what people) we associate with them.

As I discovered when researching one of my very first articles on this blog:

- Most animals learn what foods in nature are safe to eat, and which to avoid, by smelling their mother’s breath.

- People who are depressed are just as able to distinguish different smells as those in normal spirits, but the reaction in the parts of the brain that govern both sensory processing and emotion is significantly muted.

- Richard Feynman, in his book Surely You’re Joking, explains that humans lost much of our innate sense of smell after we stood upright, and describes an experiment that shows that, with a little training, anyone can learn to distinguish blindfolded the hands of a large number of people simply by smelling them once at close range.

- Humans have evolved relatively few scent receptor cells (12M) in their noses compared to rats (100M) and some dogs (220M).

- Women generally have a much stronger sense of smell than men, though sensitivity varies throughout the menstrual cycle; the leading hypothesis is that this conveys selective procreation advantage as women sense and select as mates men whose antibodies (which emit distinctive smells) complement their own.

- From swabs taken from the underarms of moviegoers leaving the theatre, most women (but few men) were able with minimal training to accurately tell with one sniff whether the movie seen was a comedy, drama, or horror film.

- Memories that are scent-related last much longer and are more intense than those connected with other senses, though recollection of objective facts is no more acute.

- Smells are conveyed to the receptors by molecules precisely large enough for detection yet small enough for airborne dispersion.

- Some dogs can smell minute amounts of explosives and other chemicals, and even subcutaneous diseases (and in a sense can even ‘smell’ time).

- Smells both convey and alter mood; global expert Dr. Rachel Herz of Brown University says “emotions are abstracted versions of what olfaction tells an organism at a primitive level”.

- Things learned in the presence of a particular odour are more easily recalled a short time later if the odour is reintroduced. Maybe smart students should set up shop in the examination room while they study for exams.

- Smells can bring on varied and profound physiological changes such as a drop in blood sucrose; in other words, aromatherapy works. Some Japanese companies promote workplace creativity and mental energy by broadcasting scents attuned to the human body clock: citrus in the morning, flora in the afternoon, cedar and cypress in the evening;

- Introverts generally have a more acute sense of smell than extroverts; perhaps their awareness of subliminal danger signals carried in some scents makes them more socially cautious.

- Perfumes, other than the musk family of scents that accentuate natural body odour, were rarely used in the west until two centuries ago.

- Some Arab cultures have highly evolved scent rituals for women, entailing the layering of scents in prescribed sequence, and the after-dinner sampling of multiple scents as perfumes and incense, a social bonding experience in which all women go home smelling the same.

- In some tribal cultures such as the Amazon Desana people, scent is the primary identifier and descriptor of individuals, and tribal language allows precise articulation of each person’s natural personal odour, the odour imparted by the foods he/she eats, the odour imparted by his/her emotional makeup, and the odour imparted by his/her fertility chemistry.

- Every individual, except identical twins, has a highly distinct and unique odour, which many animals can differentiate easily.

So how might we make use of all this to increase our awareness and knowledge of the world and how it works, and perhaps also improve our well-being?

As with a lot of novel, confusing, subjective topics, perhaps the best place to start is with self-knowledge and self-awareness. In recent years I’ve tried a whole bunch of different kinds of scented candles, placed nearby when I soak in the bath (usually with the lights off). I’ve found about 20 scents that I like, some of which I like more, or only, in a blend with other scents. And I don’t like them all ‘the same way’ — they invoke different positive emotional responses in me.

What I’m trying to do now is to figure out which ones I like in which contexts (to get me thinking more clearly, to relax or sleep, to open my imagination, to energize me, to accompany different kinds of music etc). So that I’ll know, if I’m inclined to introduce aromatherapy into my life, which ones to try when, and where.

The other thing I’m trying to do is practice tuning into the scents around me, and noticing both what I seem to be smelling, and what that scent’s emotional impact on me is.

I’m finding this monstrously difficult for two reasons: First, I have to close my eyes to prevent synaesthesia effects; it’s really hard to focus on one sense when others, which are ‘louder’ and with which I’m more practiced, keep distracting me. This can be dangerous if you’re walking along a river trail!

Even more importantly, when I’m paying attention to what I’m smelling, it’s really difficult for me to avoid using words (unspoken) to describe what I’m smelling, because there are intellectual and emotional connotations to those words that can blur my capacity to really detect and appreciate the smell. And if the word I choose is something it smells like, then I’m also going to compromise my awareness and identification of that scent with personal connotations of that thing that this new things smells like. Scientists actually use a trick of requiring you to repeat random words while you’re smelling something (called “concurrent articulation”), to prevent verbal associations from getting you off track.

Interestingly, once you’ve ‘non-verbally’ acknowledged and experienced a new smell, its memory will be stored in a different part of the brain depending on whether ‘naming’ it was easy or hard.

The second challenge in paying attention to smells, especially when you live in a city, is the distraction of other, transient smells, and the difficulty of getting close enough to the ground (where most scents are) to actually be able to smell things well. There would seem to be some dispersion rule (though it’s apparently not an inverse-square rule) that governs how close you have to be to be able to smell something accurately.

As regular readers of this blog will know, paying attention is not my strong suit. But I’m working on it.

I’m also interested in exercising my olfactory ‘muscles’ because there is some evidence that loss of the capacity to smell some smells correlates with higher subsequent onset of dementia, a disease that I’m genetically predisposed to. (Though the notorious ‘peanut butter test’ turned out to be invalid.)

So if I’m going to get Alzheimer’s, perhaps I’ll be able to smell it coming.

A reader sent me a note about the proliferation of toxic chemicals in perfumes, candles and other fragrance products. It’s a good reminder to make sure our ‘aromatherapy’ isn’t poisoning us and the people around us. Check the producers and the ingredients before buying and using these products.

After handshakes, we sniff people’s scent on our hand {video embedded

You won’t believe you do it, but you do. After shaking hands with someone, you’ll lift your hands to your face and take a deep sniff. This newly discovered behaviour – revealed by covert filming – suggests that much like other mammals, humans use bodily smells to convey information.

We know that women’s tears transmit chemosensory signals – their scent lowers testosterone levels and dampens arousal in men – and that human sweat can transmit fear.

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27070-after-handshakes-we-sniff-peoples-scent-on-our-hand/

When dogs meet they sniff each others butt. Humans wear pants, so we sniff the hand.