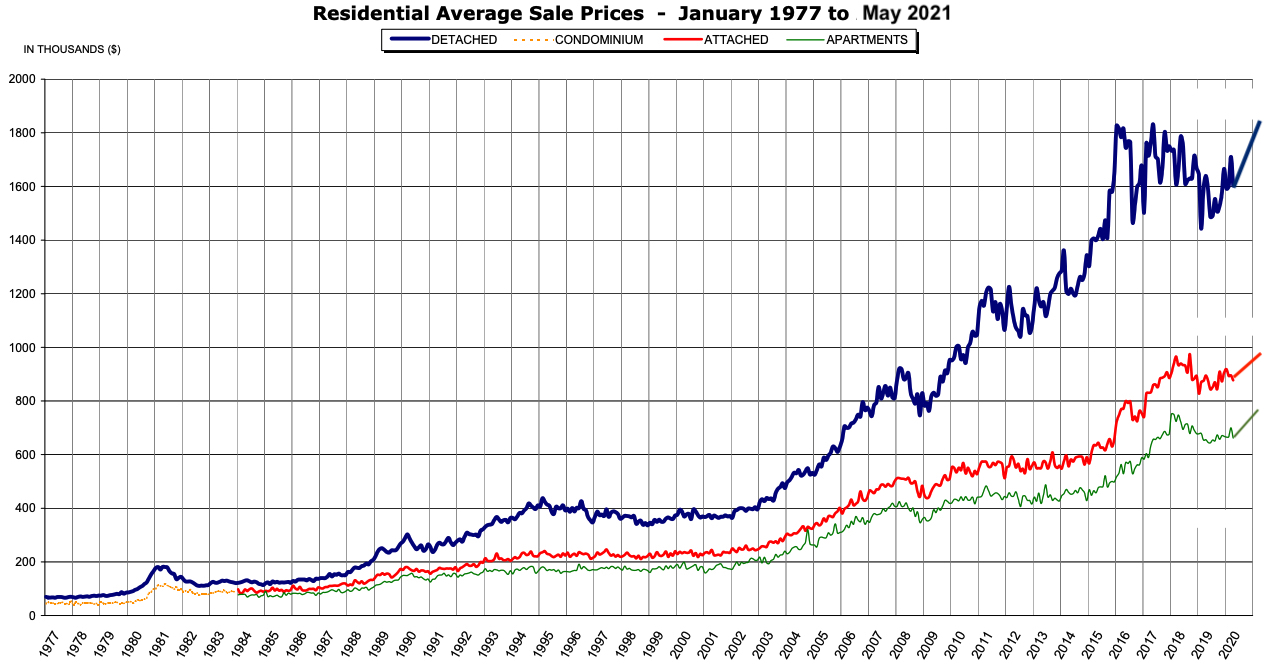

Greater Vancouver average housing prices per Real Estate Board. Note that an “average” $1.8M house requires a $400k down payment and a qualifying annual income of at least $400k, even at today’s low 2.25% mortgage interest rates. Average prices in the City of Vancouver proper are nearly double these prices. These prices are all roughly double what they were 10 years ago.

I don’t often write about personal events on my blog, but our landlady’s recent announcement that she’s planning on occupying the house I’ve lived in for the last 11 years has me thinking personally about the meaning of ‘home’. As I’m about to turn 70, moving is not the adventure it once was.

We live on an island in the Salish Sea that is also a suburb (or exurb) of one of the world’s most expensive cities — Vancouver. Housing is expensive as a direct result of the massive and accelerating chasm of inequality between the 1% and everybody else. What that wealth gulf produces is a 1% (those with a net worth over ~$5M) — a few million people in all of North America and perhaps thirty million worldwide — who are so awash in money they don’t need, that they are investing in anything and everything that looks like it might at least hold its value: Teslas, vacant land, houses in exclusive areas, and stocks on the global Ponzi markets. And many are exploiting our deliberately-suppressed interest rates to “leverage” their investments — buying a big “investment property” with a huge mortgage in areas with no rental housing, at 2.25% interest, breaking it into multiple units, and hiring property managers on commission to generate combined rental income from it of from $8,000 to $25,000 per month, per house.

Think about this — you can borrow money at 2.25%/yr and invest it in a real estate market (or stock market) whose prices doubled in the last decade (ie increased by 7%/yr). When the actual rate of inflation is over 10% (the fake ‘official’ rate is 2%), can you see why we have massive bubbles in the real estate and stock markets? This is just asking for trouble. If interest rates spike, look out.

The 1% are doing this because, in some areas like Vancouver where the housing bubble is most frenzied, the only people who can still afford to rent a “whole house” are corporations (for whom it is a tax write-off and a perk for visiting execs), and executives with high-six-figure incomes. Of course, those executives aren’t the least bit interested in renting, as they already own large and usually multiple properties. So the buyers of real estate as an investment (a recent study of West Vancouver showed that close to a third of residents there own more than one home), have two choices: leave them empty and then flip them as prices continue to soar, or break them into multiple units and charge $2-5,000/month rent to each tenant, to recover the mortgage payments and property taxes.

Both are happening. On our island, at least 20% of the homes are vacant all or most of the year; the owners use them as vacation homes in the summer and are rich enough they can let them sit empty the rest of the year and not have to worry about pesky tenants. Some “executive lots” here have sold for $2M+ just for the lot. It’s an open invitation for money-launderers. And as each nation simultaneously creates more and more billionaires and more and more homeless people, those billionaires will just keep pushing up the price of lots, and homes, and rents in “desirable” areas worldwide.

Of course, if (when) interest rates spike to the actual rate of inflation, this whole house of cards comes crashing down. Double the rent on a studio apartment from $2,000 a month to $4,000 a month (there are ways to get around the controls) and you’ll find yourself begging for tenants. Keep the rent at its current (outrageous) level and you’ll be unable to meet your mortgage costs, and as resale prices plummet you’ll be under water. Except of course for the 1%, who will simply push the numbered companies they used to buy the houses, into bankruptcy, get a nice tax write-off, and leave the bank holding the bag — and the house empty.

Our island has been dealing with a massive exodus of residents who don’t own their homes, for most of the 11 years I have lived here. They are evicted (and many are “reno-victed”) as the owners decide to sell at a nice profit and use the profits to buy elsewhere where they can get higher rents, often by adding basement “suites” and separate entrances to what were once “single-family” dwellings. Or the owners just sell off and buy land or houses that they can raze and replace with monster homes, and resell, so they don’t have to deal with tenant ‘rights’ and rent increase ceilings.

There is almost no money being spent in our Ponzi bubble housing market to construct new, “affordable” rental accommodations — it’s an unprofitable business.

Unlike most of my many, many island friends who’ve been evicted over the past few years, our eviction won’t cause us any suffering. We’ll have to move to a smaller, less beautiful place, at least until the market collapses, but that’s all. But there is of course a certain culturally-conditioned shame in suddenly being ‘forced’ to move from the place you’ve called home for so long.

And that’s what’s got me thinking about the whole subject of “home”. Besides being an exhausting, nerve-wracking (in volatile markets), ever-depreciating “investment”, and one that is, for most, the lion’s share of their total net worth, what does it mean, exactly, to call a place “home”?

Here are some of my thoughts:

- For many, our home is a symbol of status and of self-worth. We talk about people being “house-proud”. Perfectly functional homes are torn apart and “renovated” simply to display this season’s preferred interior colours and designs, to “keep up with the Joneses”. We feel better about ourselves if our home brings expressions of awe and envy from friends, family and visitors. And vice versa: If our home is shabby, or if we lose it to eviction or foreclosure, we are filled with shame.

- Our home’s neighbourhood not only reflects on who we are, it empowers or inhibits us and our families for our entire lives. Proximity to “the right” schools. Our ability to impress the boss, the client, the boy/girlfriend, the bank. Access to people with power and influence. The prevalence of redlining and other racist and discriminatory practices.

- Our homes are the anchors of our wage slavery. The increasing cost of homes means the need for commensurate (7%/year) increases in income just to stay in the same place relative to housing costs. That means doing whatever we have to do to get not only raises but promotions. We may say “I no longer want a career“, but if we do we may be essentially saying “I no longer want a home”.

- Having a home brings with it the potential psychological impact and trauma of dislocation, whether due to transfer, eviction, foreclosure, or simple incapacity to keep up with the insane upward spiral of home costs. Home for many is the bedrock of security, or continuity, of connection to the earth, the world, and to friends and society. “Starting over” in a new, often less safe and attractive neighbourhood, can be especially traumatizing to children, and to seniors on fixed incomes who fear, often justifiably, that worse may be yet to come.

- Home is the reinforcer of caste. While our caste, in the updated sense Isabel Wilkerson uses the term, may be largely determined by our physical appearance, our inherited status and wealth, and our profession/employment, our home plays an enormous role in reinforcing this determination. Live in the right place, your wealth and power will almost inevitably increase, and you will be treated accordingly by almost everyone in society you meet. Live in the wrong place, and you are locked into the lower castes for life (and beyond, through your children and the influences they will have growing up, and the ways they will be treated).

- In many indigenous cultures, home is sacred. It is where you belong and what you belong to, not what belongs to you. It gives you a connection to the land and the resources and learning needed to reside and thrive in place. It defines you.

Where will it all end? Like everything in our modern industrial society, the current definition of home, the anonymity of neighbourhoods, the grind of an ever-longer commute from “affordable” residential areas to the places where all the jobs are, the spiralling price of land and housing — none of it is sustainable. It will collapse. But in the meantime it will get worse. There are no “solutions” to a problem that is systemic, global, and worsening at an accelerating rate. No one has the power to fix it.

As we run out of cheap oil, we can expect transportation costs to increase at an even faster rate than housing, and then we’ll encounter a vicious cycle: the soaring cost of transportation will make areas close to good jobs, good schools, in safe, clean, attractive neighbourhoods even more valuable, exacerbating the already massive inequality we are now dealing with. We will reach a breaking point at which most of the bullshit jobs have been automated, and most of the population will have joined what is being called the precariat or unnecessariat — permanently unemployed or severely underemployed. They will be needed only to consume enough mass-produced products and incur enough debt to keep the economy “growing”. So our “first-world” nations will quickly start to look like so-called “third-world” nations — a tiny minority living in staggering opulence with many servants, and the vast majority living in ghettos with just enough money to keep them yoked to the consumer wheel.

Where is the outrage? People can’t be outraged about a situation if they’ve never known anything different, and today’s younger generations have already been primed to expect no steady job or job security, no pension, and certainly no home that they can hope to “own”. This is happening just slowly enough to keep the people in their place, resigned to massive inequality as just “the way things are”.

Much of the world has already lived this way for generations, and soon, like everything else in our globalized economy, this will be our lot as well.

And then, the economy will collapse. We’ll pay for our excesses during this long, oil-financed bubble. And then we’ll discover what “homeless” really means.

Importat topic that only gets occasional attention. Thanks.

It’s been this way in Silicon Valley for decades. Friends and family have moved away to where housing is (somewhat) more reasonable.

Neighborhoods become sterile showcases of wealth.

In a few minutes of bicycling, I find myself in encampments of the homeless, along the creeks, under freeways.

Result is that everyone below the 1% is anxious, stressed.

Thanks Bart. Hear it’s the same in a lot of cities around the world. Not expecting government to solve it, as it would require draconian (ie unpopular) action.

I have never rented or had a mortgage. I have been provided housing by living with family, by the Peace Corps, by a co-worker that had a family farmhouse become vacant for a year and by a boarding school where I taught and where my wife was a girls’ dorm supervisor.

Too many people refuse to consider my family’s strategy, which was to live in places like those, save money, buy rural land for cash where we could afford it, save money, buy lumber for the shell of a house, built it with our own hands and move in, save money, then gradually outfit the interior of the house as we could afford it. For several years some of the interior “walls” were carpets hanging from the ceiling. Our first home required 25 cubic yard of concrete, which we mixed and placed one cubic foot at a time; 675 batches in a little electric concrete mixer running off a small generator.

Of course, this strategy requires prioritizing where one lives rather than the job one has. My wife and I had to work at jobs that were available where we lived, keep our expenses as low as possible by providing for our own utilities (heat, water, power), raise as much of our food as possible, and delay having children until we were well settled (10 years).

I’m not saying that this strategy for housing is possible for everyone, especially since things have changed a lot in the last 50 years, but it is probably feasible for far more people than most folks expect. Prior to building our our first house, my main carpentry experience was building treehouses as a kid (and there weren’t any house-building YouTube videos to guide me later).

Building their own house is something that most young people could do if they really tried. Hardly anyone thinks of trying.