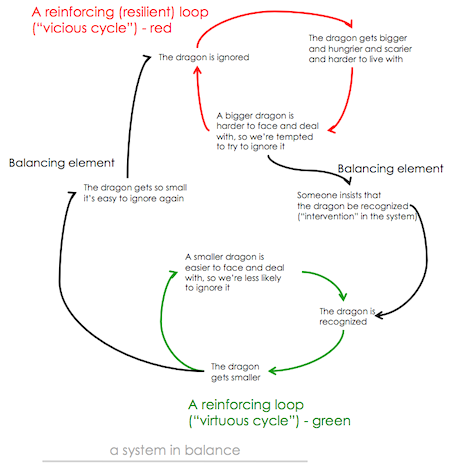

illustrative system diagram from my post on Systems Theory

The fundamental problem with systems is the illusion that they actually exist. A system is a concept — the mind’s patterning to conclude that a bunch of things or phenomena are in some way connected or related. Mattress-makers grandiosely describe a mattress plus a foundation and frame as a “sleep system” because presumably they somehow “work together” to improve sleep. The idea is hyperbolic, but it sells, and illustrates how our minds love to see connections and patterns and “systems” everywhere.

A human-made machine (such as an automobile) is often called a “complicated system”. Its parts are designed to “work together”, and over the short run you can reasonably ascribe cause and effect to its interactions, and make diagnoses and predictions of its “collective” behaviour accordingly. These “complicated systems” are designed to be controlled by their makers. Over time, however, complicated systems always decay and fall apart. Your car will rust and its parts will abrade and decompose, victims to natural factors that are not “part of the system”. Cars, buildings, roads, nuclear reactors — without a ton of continuous intervention to keep these unnatural human creations from degrading, they will all fall apart quickly, often in spectacularly ugly ways. And while we see them as integral, as parts comprising a “whole”, they are so only in our minds, not in any “real” sense of being self-managing, autonomous or complete. They are only abstractions, appendages, extensions of us dependent on our constant intervention, no more “systems” than the twigs a raven uses to flush food out of a rock crevice.

The “natural factors” that eventually destroy complicated constructions are parts of what we call, incorrectly, “complex systems”. Molecules, cells, bodies, organizations and cultures are all, indeed, complex. But they are not “systems”. The more we learn, the more we appreciate that these “systems” are not integral (there is no scientifically rigorous way of defining or distinguishing what is “part” of them from what is not). They are so complex that there is no way of knowing all their elements or “components” even if they were integral. And while we might (in our determination to understand and control these systems) assert consistency, correlation and causality between some intervention, process or action within the “system” (e.g. taking medicine, or a placebo) and some result (relief of symptoms of “illness”), we can’t hope to do so reliably. It’s all trial and error, and repetition rarely produces the same results.

Since human-designed “complicated systems” all require a controller, we look for a controller in what we see as “complex systems” as well. We see the brain as the controller of the body, although that organ actually evolved to serve the body’s other priorities, and has never been “in control” of anything (and some intelligent species, like the jellyfish, do very well without brains at all).

We see gods or a “higher intelligence” as the controller of what we call “ecosystems”, because we can’t fathom such “systems” evolving uncontrolled and without purpose. We see “leaders” as the controllers of organizations and cultures, despite evidence that what we conceive of as a bounded, integral organization or group of people is simply that — a conception, a patterning, the collective actions of a group of people subject to an infinite number of behavioural influences, most of them unconscious and completely uncontrollable, most of them outside the so-called “system”.

Nevertheless, we would like to believe that these “complex systems” actually do exist as definable, integral, predictable, controllable entities. Science would have us believe we will eventually understand how all matter is constructed. Medicine would have us believe we will eventually be able to treat and cure all “diseases” of the body, and even construct complete “perfect” bodies. Executives and consultants would have us believe we can powerfully understand and control the behaviour of organizations (and that they should be paid handsomely for allegedly doing so). And politicians, economists and activists would have us believe we can (and urgently “need to”) understand, control and change our entire culture, to make it “better”.

But none of these “systems” — simple, complicated or complex — actually exists. They are just concepts, inventions of the mind, fictions. Organizations are not “made up” of a defined set of people, processes, assets and technologies. That is all patterning of our minds, a kind of grandiose wishful thinking that we can delineate and control what this defined set of things does. Likewise our bodies are not “made up” of organs and cells; as Richard Lewontin has explained, attempts to scientifically analyze any physical entity separate from its environment are inherently flawed because nature and nature’s laws do not recognize boundaries between them or independent actions within them. “Complex systems” are infinitely complex, unbounded, and not “whole” in any meaningful way, and hence inherently not “systems” at all, except in our minds’ imaginations.

So when we look at something as if it were a system, in order to try to understand or change it, we are looking at an invention, not something real. When we think we see the components of atoms or cells or bodies or organizations or cultures as something definable, distinct, knowable, predictable and hence controllable, we are seeing what isn’t there, so it’s not surprising we are disappointed with the results of our interventions.

What if we instead saw each of these complex things — atoms and cells and bodies and organizations and cultures — as infinitely complex, unbounded, unknowable, unpredictable and uncontrollable, not as defined parts of anything larger or as made up of identifiable parts? In other words, what if we took off the lens of the modern scientist, model-maker, representer, and analyst, and instead saw things as they really are: unfathomable, mysterious, wondrous, infinitely beyond what we can possibly know or even sense? What if we stopped seeing things iconically and separately, and instead realized with absolute humility and utter astonishment that our senses and minds can only appreciate an infinitely small (though evolutionarily useful) fraction of what everything actually is?

This is not a call for some kind of mystical evangelism. It’s rather a convoluted way of saying: Stand still and look until you really see. Or perhaps more accurately, until you stop seeing what isn’t really there.

This is not easy. When we draw an eye on a piece of paper most of us tend (unless we’ve been re-trained) to draw the icon of an eye — an almond shape with a two concentric circles inside it. But an eye is vastly more complex and unbounded than this clever but simplistic pictograph. The artist is able to “see” this. Most of the rest of us will actually draw a more realistic-looking eye (or face, or anything else) if we turn the picture of what we’re drawing upside down so we don’t interpret its elements simplistically and iconically, and just draw the shapes and spaces and shadows that actually constitute what we see.

Suppose we tried to see everything this way — without interpretation, judgement, presumption, simplification, intention or assumption of accuracy or completeness? What if we looked (physically and metaphorically) at everything with wonder, astonishment, love, appreciation, curiosity, humility and acceptance — the way a young child looks at things, before being entrained to look with fear, anxiety and other blinding filters?

I remember looking at things this way — without any attempt to make sense or use or meaning of what I was looking at. I remember that what happened then was that the illusion of a boundary or separation between “me” and what “I” was looking at vanished. There was only everything, stillness, wonder, aliveness, connection, one-ness.

Mostly now I am too fearful to be able to do this. I fear losing my self, my security, my control over my situation and responsibility for it, my mind. I “know” that none of these things I fear losing is real, but I fear their loss nonetheless. As I watch the hero on the screen gripping perilously to the rope over the precipice, I can’t help gripping ferociously the arm of the seat from which I watch this imaginary occurrence. I’m too “smart” for my own good.

The problem with systems is that we’ve forgotten that they aren’t real. So we try desperately to create them, to recreate them, to understand them, to sustain them, to improve them, to make them serve us better, and then bemoan their endless failings. Like our gods and our cultures and our leaders and our organizations and our minds and our bodies and our models of what seemingly is, these “systems” are only imaginings, ideas, patterning, wishful thinking that doesn’t actually represent anything real, so it should be no surprise they “fail”, they disappoint us. Still, we say, we have to try to make them better, we have that responsibility, we have no choice but to seek and strive and struggle and persevere.

But we’re wrong. It’s only when we let go of the struggle to improve what isn’t real that we’ll really see what is. And only then will we see what we can effectively do (and can’t do, and can’t help doing). Our actions then will not “make the system better”, since there is no system to make better. Instead, they might actually make a difference, make us better suited to this awesome, beautiful, terrible, unfathomable world.

Exactly. Great post. Thank you. Interestingly this can straight after listening to an interview with embryologist Jaap Van Der Wal on how the body is not a collection of parts but can only meaningfully be understood (and experienced) as an irreducible “performance”. http://www.liberatedbody.com/jaap-van-der-wal-lbp-057/

Your essay could be the beginning of discussion “WHY we don’t want (or can not) understand the nature of systems and the systems in nature”. On the other hand following your blog for couple of years I know you aren’t open to discussions, so it’s no use to continue. If (hopefully) I might be wrong please feedback on my gmail.

To my mind, it’s not so much that systems don’t exist, it’s that–as with anything else–“the map is not the territory.” Ecosystems, bodies, organizations, all of these are useful ideas, in context, that can also be applied in a problematic manner . . . just like any other idea.

> “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form” That is, form is form, emptiness is emptiness.”

Shobogenzo, Maka-hannya-haramitsu, Hee-Shobogenzo, Maka-hannya-haramitsu, Hee-Jin Kim (Flowers of Emptiness, p.61)

* The central importance of emptiness in Buddhism can be seen in the Zen/Buddhist axioms, “All things are essentially empty,” and “Emptiness is the true nature of all things.”

The Buddhist doctrine of emptiness is multifaceted (ie ‘complex’ not ‘complicated’). The truth of any facet of the doctrine is dependent on its context in the complete form. To be ’empty’, as in the Buddhist axiom, ‘All things are essentially empty,’ means to be empty of selfhood, to lack independent existence. To be empty does not mean to be unreal, illusory, or nonexistent, as is commonly misunderstood. *

http://www.zenforuminternational.org/viewtopic.php?f=64&t=10583&hilit=+avalokitesvara#p162975

l

Wow, interesting article! Its making me think a bit. I work with systems a lot, and systems tend to control a lot of my thinking and behavior. I’m not certain that all systems were meant to be permanent- You argue that a car is a complicated system that will decay and fall apart, but from an engineering standpoint that automobile system was designed to last for a finite amount of time, using a methodology known as Product Lifecycle Management (PLM).

Your argument seems to be that things are too complicated and we should give up on trying to understand them and just stand in astonishment of how amazing everything is, but I don’t see how that makes any improvements outside of a personal mental state…