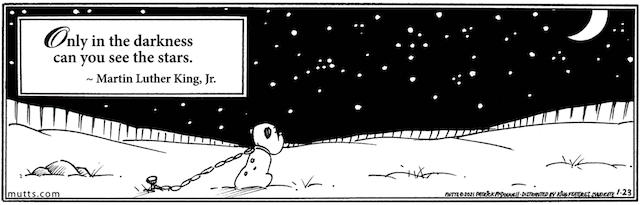

mutts comic strip by Patrick McDonnell; Patrick is a huge champion of animal rescue and shelter animals, and his book The Gift of Nothing is a classic for all ages

A woman I know once told me that the reason I come across as arrogant is that, while I say “we’re all doing our best”, I really don’t like spending time with most people. It implies, she said, that “our best isn’t good enough for you.”

I can see how that comes across, but my misanthropy doesn’t come from any sense of superiority or judgement. My instinctive aversion to most people is pretty much the same as my instinctive aversion to junkyard dogs. They’re doing their best. They’ve been conditioned to be threatening and violent. They’re tragic figures. Like a lot of people I know. But that doesn’t mean I want to be around them.

Last summer, in dismissing the argument that humans are innately violent, I referred to the late Canadian naturalist John Livingston’s remarkable 1994 book on human nature, The Rogue Primate:

John argued that humans have domesticated ourselves, possibly because our species appears to have all the qualities needed for easy domestication: docility and tractability, a pliable or weak will, susceptibility to dependence, insecurity, adaptability to different habitats, inclination to herd behaviour, tolerance of physical and psychological maltreatment, acceptance of habitat homogeneity, high fecundity, social immaturity, rapid physical growth, sexual precociousness, and poor natural attributes (lack of speed, strength, and sensory acuity). We share these qualities, he argued, with most of the creatures (and many plants) we have domesticated. The only difference is, we domesticated ourselves.

Domesticated creatures, he said, are by definition totally dependent on a prosthetic, disconnected, surrogate mode of approaching and apprehending the world, to stand in the place of natural, biological, inherent ways of being. Such creatures see the world through this artificial prosthesis, instead of how it really is, and this self-domestication is what we call civilization.

When you can’t see the world as it really is, but only through an artificial, distorting lens, it is not hard to become untethered. I watch with dismay as incompetent pet owners try to “train” animals by yelling at them, hitting them with newspapers or choking them with chain leashes. Melissa Holbrook Pierson in her book The Secret History of Kindness explains how and why this negative conditioning invariably backfires. And, she says, it is precisely this kind of (usually well-intentioned) conditioning that makes humans the way we are — for better and for worse.

Domestication is defined as “adapting a wild species for human use”, though a more generous definition might be Cambridge’s “the process of bringing animals or plants under human control in order to provide food, power, or company”. These definitions might just as easily apply to the word “slavery”. Despite romantic notions that dogs and humans, for example, “domesticated each other”, domestication is necessarily a coercive process, where the once-wild species is forcibly deprived of its freedom by its domesticators — us. The Dawn of Everything explains what happens to a species when it loses its freedom.

When you live in a high-stress, high-competition, high-scarcity (artificially created) modern culture, and when all those around you live in a situation of constant precarity, it’s not surprising that our conditioning of each other — our self-domestication — produces in us mostly the human equivalent of traumatized guard dogs.

I dream of a world in which it is otherwise. There is no reason why the human experiment has turned out the way it has. In the world of my dreams, as in the world of wild creatures not yet diminished, threatened and encroached upon by the human plague, there is no disconnection, no distrust, no sense of precarity. If, awakening from such dreams, I suppress my emotions, it is perhaps because I cannot bear to think that we might all be living in such a world, had we not, while all doing our best, fucked up the planet, and each other, so badly.

So when I get even a small taste of all the suffering in the world, as when I see or hear a domesticated animal being neglected or abused, I have no choice but to turn away. I could never work in an animal shelter — I would either kill someone or go mad with grief.

And so, instead, I make up characters in my writing, characters who are more interesting, more bearable than the ‘real’ people I meet, ‘real’ people who are struggling impossibly to heal from trauma, or who have so cut themselves off from their feelings and awareness of the world (not so hard to do, as our conditioning makes this easy and acceptable) that they feel almost nothing at all. ‘Real’ people who, thanks to their conditioning, cannot (and perhaps dare not) imagine a world different or better than the one they live in. ‘Real’ people who live lives of quiet desperation with a veneer of coping and cheerfulness, convinced that, as it cannot be otherwise, their lives must be good.

The characters I create in my writing are, to the best of my ability, unrestrained by domestication — they are free, uncivilized, connected, un-traumatized humans. The kind of people I would like to meet, and learn from. Not that they would have me, I suspect.

And I also make up funny, wild, implausible stories about people I see sitting nearby in tea houses or walking on the street. And I turn off the sound of movies and TV shows to create my own plots and characters, which I find far more imaginative, more interesting and less maudlin and infantile than the manipulative, self-indulgent, simplistic, preachy, predictable, juvenile pap that Hollywood churns out.

My invented-but-not-impossible characters are the kind of people I want to surround myself with, to engage and imagine and laugh and play with, and to love. I don’t blame the world of ‘real’ people for not being that. They have had no more choice than to turn out the way they have, than the junkyard dog has had. The chains go on at an early age, and, unless you’re incredibly fortunate, never come off.

I guess that makes me a misanthrope, but not a condescending one.

I have been one of the junkyard dogs most of my life — conditioned by fear and anger, easily triggered. And that despite the fact everyone in my life has been doing their best, including their best to help me, to be what I really wanted to be — free, mostly. In recent years, for reasons I do not understand but which probably stems from privilege and good fortune in the form of the unusual people in my life, it seems the chain is no longer there, though, cautious and cowed and distrustful, I still act as if I am chained, restrained now by an ‘invisible fence’ of my own invention. I am afraid of exactly what I have always wanted. Why? Aha; that is the question.

Before, it was easy to bark and snarl at the junkyard dogs around me. Now, they just make me sad. I cannot bear what our self-domestication has done to our too-smart-for-our-own-good species, and how the mutual self-conditioning of 7.8B others keep us in thrall, keeps us believing, keeps us yanking hopelessly at the chain, keeps us believing that this is the only way to live.

Though, even more sadly, that reinforced, endlessly and relentlessly conditioned belief now means it almost assuredly is the only way for our species to live, until it collapses, soon enough. And after that, who knows? Maybe like Robert Sapolsky’s extraordinary baboon troop that lost all its brutal alpha males to poisoning and became a peaceful matriarchy, our next societies will be differently conditioned, perhaps even undomesticated and uncivilized. We can dream. I cannot bear to think otherwise.

“When you can’t see the world as it really is”

How silly, there is no absolute “ding an sich”, EVERYTHING you, me, anyone, sees is a kind of model we developed/were born into, which is more or less “adequate” i.e. allow us to survive and thrive for a while, how is your score so far?

Not so bad it seems despite “non duality”. :-D

Thanks for the reflections on misanthropy.

My own spin on this has often been a variation of Gramsci’s ‘my mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic’ (or his famous ‘pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will’). In my own case, I tend to say that ‘my mind is misanthropic, but my will is compassionate [or sympathetic].’ Or rather, I consider the human species to be an ongoing disaster or existential tragedy, but I can muster/will some compassion or sympathy for individual human beings, or more often non-human beings.

You spoke from my heart… Speechless… Amazing. Thank you for sharing it.

Thanks Paul, and Sorcerer B.