Have you ever had the experience of learning several things, each of which evolved completely independently, such that when you put them together you get a very satisfying or profound new insight? This recently happened to me.

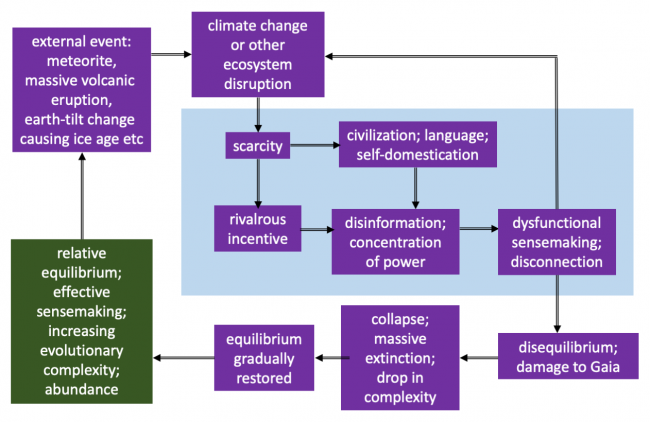

As an admirer of Gaia theory, I was delighted to discover Tim Garrett’s metaphoric thinking about collapse and mass extinction in that context — Earth & Gaia as a single organism, now tragically and seriously diseased through a well-intentioned evolutionary misstep we call civilization, in the late throes of inevitable collapse.

That got me thinking about the ’cause’ of this disease and how/why this evolutionary misstep might have occurred. A clue to that came in the form of a video interview sent to me recently by Tom Atlee and Tree Bressen — an interview with the evolutionary philosopher Daniel Schmactenberger on the subject of sensemaking and disinformation.

One of Daniel’s arguments is that the rise of our complex civilization corresponded to a rise in disinformation, which in turn has produced an incapacity to make sense well, which has then led to disastrously dysfunctional behaviour.

The disinformation arose, he says, because memes are not at all like genes — while genetic modifications ‘succeed’ based on whether they help the organism ‘fit’ well as part of Gaia, memetic modifications ‘succeed’ based on their persuasive power, power that can often be coercive, and which while in the best interest of its propagators is often not at all in the best interest of the whole.

Religions, corporations and states have succeeded, he says, because their champions and leaders are able to use disinformation to arrogate power into vast hierarchies where their intimidated followers are ‘persuaded’ to proxy (delegate) their sensemaking to the leaders, and end up incapable of doing their own sensemaking well. Power is seductive, addictive and corrupting. Three kinds of disinformation are used: Information that is not true, information that is not truthful (where the propagators don’t believe it themselves), and information that is not representative (where the propagators are misleadingly selective in what they do and don’t disclose). When we’re surrounded by more and more dubious information, we are forced to proxy ever more of our sensemaking to those we trust, and to align ourselves (for safety) with others who proxy their sensemaking to the same authorities. Even worse, as this information becomes increasingly suspect, we lose the ability to trust others altogether, and our society fragments and has to be held together through heightened disinformation and fear.

Civilizations arise, many believe, as an attempted adaptation to circumstances of great scarcity and commensurate stress — we struggle together and cede personal sovereignty because we sense we can’t survive otherwise. This is what John Livingston calls our propensity for self-domestication. In times of abundance, there is time and freedom to exercise authentic, sovereign, unbiased sensemaking, and trust, truth, truthfulness and representativeness of information are encouraged and empowering. In times of scarcity, however, most people are too busy to even learn the skill of sensemaking, so they must delegate/proxy it to ‘representatives’, leaders. The result is that inequality, disinformation, hierarchy, and sociopathy of leaders are all enabled and encouraged and truth is sacrificed. Daniel’s conclusion: “Rivalrous incentive (motivation to compete in zero-sum games in times of scarcity) has been the generator function of almost all the things humans have ever done that have sucked”.

What most of us end up then doing is mere “meme propagation”, which is non-thinking; it is purely reactive and has no sovereignty. Most people, Daniel argues, now have a “memetic immune system” that blocks any idea or belief not consistent with their worldview, and protector memes that have been instilled in them by leaders/proxies that prevent critical thinking. And in such a world it’s not safe not to have an in-group that shares one’s worldview, so there’s enormous pressure to conform/adapt to some ‘in’ group and identify fiercely and uncritically with it and its ideas.

If this is what has happened, how can we best deal with it? Daniel says he would like to see people practicing doing the following (because sensemaking well takes practice):

- Challenge your own beliefs and be curious about those that don’t fit with your worldview.

- Seek to understand, not to be understood.

- Understand why people believe what they do.

- Reconcile conflicting ideas to reach a higher level of understanding and perspective; this often requires, and produces, novel insight.

- Debate doesn’t help “make sense”; it’s a “narrative warfare” process that emphasizes rhetoric and winning over understanding. By contrast, dialectic is the process of trying to make sense together, a higher order of thinking.

- We can learn to at least love each other’s evolutionary trajectory; this requires a tolerance for nuance, emotional vulnerability (to create a sense of trust and safety), and humility. Most people have few relationships with those qualities.

- Set aside your impulse to be right and your identification with specific beliefs and ideas. Look at your own biases; learn how to learn better; and build healthier (and better sense-making) relationships.

- How might we remove the incentive for disinformation (zero-sum game politics and competitiveness), he asks, by aligning the definition of well-being of various agencies (individuals and organizations at all scales) and reducing rivalrous environments?

I confess to having some doubts about our capacity to do much of this, and I sense that Daniel might as well. But it was his final thought in the video that got me linking his ideas to Tim’s: He uses the metaphor of the body, and notes that the cells and organs that comprise us are able to balance their own self-interest with that of the whole body; they make sense together holistically, and share information in such a way that better decisions are made than any ‘component’ could possibly make independently. Then he notes that in cancer-ridden bodies self-interest of the afflicted cells trumps collective interest, and the result is that the cancer and the body it infects often both die.

—————

So here’s the synthesis of these ideas I’m thinking about:

You may be familiar with the idea of Bohmian dialogue — an exchange of thoughts, information and ideas among a group of 20 or more people with some shared passion, that is without intention and which leads to understanding and ‘collective intelligence’ but not decisions. It is in many ways similar to what some indigenous cultures have apparently always done when they get together, how they collectively make sense of the world. And it is analogous to what the cells and organs of the body do to exchange information to make sense of the whole body’s situation. There are no ‘decisions’ in the sense of consensus, voting, delegation or analysis; what is done after the sharing of information is acknowledged as the only thing that could have emerged from the collective understanding.

I would argue that in fact this is what humans naturally do, that it is what every creature does, and it is what Gaia does — sensemaking. Not just our purpose, not what we’re meant to do. What we do. Sensemaking defines us. We — genes, cells, organs, creatures, Gaia — are sensemakers.

I would further argue that language didn’t evolve, as my cynical self has long believed, as a means to convey instruction down and information up in large hierarchies. Rather, it evolved to enable a better dialectic (collective investigation of what is true), and better epistemology (collective understanding of what is true) through (Bohmian-style) dialogue. Better collective sensemaking than what any individual could possibly discern or understand. It evolved because it was, at least at first, good for the whole. But in times of scarcity, language seems to be quickly appropriated as a vehicle to obtain and secure power through disinformation.

By this reasoning, it could be said that (1) scarcity led to “rivalrous incentive” which, coupled with language, enabled and encouraged the use of disinformation to achieve concentration of (addictive, corrupting) power, and also led to widespread dysfunctional sensemaking; and (2) this loss of capacity for healthy sensemaking (our very essence) created the disconnection (from Gaia, and from the truth) of civilized humanity, which has enabled massive damage to the planet and brought about the sixth great extinction.

What is happening to civilization now seems more a dissolving (ie a weakness and crumbling of foundations) than a collapse of its component parts — states, corporations, communities, hierarchies of all kinds, and even many one-on-one relationships are largely unsustainable and starting to fall apart from the bottom up, and this dissolution is accelerating. None of these can survive in the absence of the capacity for trust and good sensemaking. And nothing can survive ‘separately’.

It is highly likely that Gaia will survive, though probably in a radically-changed form. It has survived mass extinction events often enough before. Whether humans will still be a part of it, post-collapse, is anyone’s guess, but as Tim has argued, that’s entirely out of our hands.

Which brings me back to the question that prompted this article: What if there’s nothing we can do? We may engage in insightful dialogue with informed people with whom we have open trusted relationships, and we might even overcome some of our personal biases by understanding why people believe things we find preposterous. But where does that get us? We might become better sensemakers and have a greater appreciation for and sense of belonging to Gaia, and become more appreciative, understanding and non-judgemental about our current predicament, and better witnesses as it comes apart, but when the SHTF that will be cold consolation for the long dark hard years of collapse.

The answer, I think, for now, to the question What if there’s nothing we can do? is simply that we are sensemakers — we cannot help trying to make sense of things, even if and when our sensemaking is dysfunctional. Even the lamest meme-propagators are doing what they do out of a desperate drive to make sense of things — even if their memes don’t make any sense at all. As with our approach to death, we may approach that realization of our rather humbling true nature with equanimity and compassion or with rage, but neither will affect the outcome.

—————

I can’t resist taking this thesis one step further (this may be too abstract or too far out there for some): Sensations are metaphors for reality. ‘We’ sensemakers — genes, cells, organs, creatures, Gaia — cannot know what is real, but we can sense, we can ‘make sense’. What we think of as reality is metaphor. Metaphors are our truths. Reality is not our business.

From that perspective I am quite comfortable with the idea that the sense of having a separate self is illusory. It is illusory because it, too, is a metaphor, an idea concocted in the brain, just as our sensations, and, scientists are now starting to say, just as time and space are. The metaphor of the self is a compelling metaphor because, like all good metaphors, it helps the brain make sense of things. The metaphors of time and space make sense because they give the brain a place and means to organize, sort, store and retrieve its sensations, the messages it receives from the ‘rest’ of the body and the ‘rest’ of Gaia. It doesn’t matter whether they are inventions, and not real, as long as they make sense. The metaphor of the ‘separate self’ makes sense because it provides a position, a context, for the making of sense of everything ‘else’. That there really is no ‘self’ and nothing ‘else’ is of no importance. Metaphor is the brain’s ‘stand-in’ for a reality it can never know. Metaphor is its truth. Reality is not its business.

The very idea of this is astonishing. But, of course, it makes no sense.

We are the only virus with a skeleton & extremely destructive.

Pardon the pun, but it makes sense to me.

Have our lives become too complex to make sense of, and the majority of the human species are mainly concerned with day to day survival, so comprehending the forthcoming collapse is out of the realms of sense for mosy people.

Are you aware of this writer? I find both your writings highly thought provoking and enjoyable

http://ranprieur.com/essays/slowcrash.html

Thanks Gavin. Well aware of Ran’s work; he was one of the first bloggers on collapse and very influential in my own research on it.