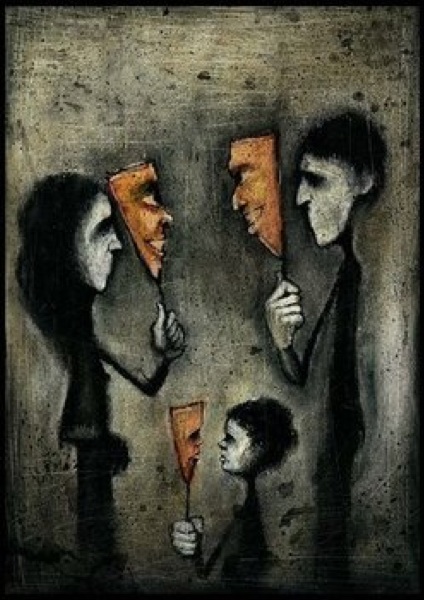

Artwork from the collection of Nick Smith, “possibly by John Wareham”.

At first I wanted to believe that the adults around me were just acting. Surely they didn’t believe what they were saying; surely it was just a big secret joke, a playing of roles in a great play, and soon they would let me in on it.

And then I wanted to believe that the kids in my first school were seriously ill; this cruelty, anger, terror, unhappiness and dishonesty they exhibited must be just a mask, an acting out of some horrible trauma they had been subjected to. But so many! And the teachers behaving as if this were somehow normal! Please, I said, let me wake up soon from this impossible nightmare!

Later I wanted to believe that there was just some big misunderstanding about the world of work. Why would so many submit themselves day in and year out, for most or all of their lives, to grinding, meaningless, humiliating jobs? There must be something wrong here; will someone please explain how this ghastly situation arose and when (soon!) it will be corrected?

After that I wanted to believe that there was this tiny number of us, fellow exceptional sensitive and intelligent souls, who understood how outrageous and dehumanizing our supposedly civilized society was, and that together we could find a way to escape it. My anthem: We gotta get outta this place!

And then for a long time I wanted to believe in myself: that with intelligence and effort I could rid myself of the relentless noonday demons, and recognize and heroically remedy what was so horribly wrong with our world. So many, it seemed, were depending on me!

And then after that I realized I couldn’t do it myself, so I wanted to believe I could “find the others” — the group smart enough and imaginative enough (and special and beautiful enough) that, with my help, could really make a difference.

But the more I learned, the more I came to believe that everything was hopelessly falling apart, and that the sixth great extinction of life on earth had been accelerating for millennia and nothing I or anyone could do could slow its inevitable unraveling and ultimate collapse, perhaps even within my lifetime.

Surprisingly, this new belief was liberating, rather than depressing. Though I kept wondering if I believed it only because it let me off the hook.

Recently I’ve found myself wanting to believe that none of these things that all my life I had hopelessly wanted to believe, were actually real. That everything that this brain had invented and seen as real since it first became aware of the strange beliefs of adults when I was a small child, was just an illusion. That what I had been searching for, the explanation of what was intuitively, inexplicably, terribly, impossibly wrong with this world, was a foolish and hopeless search, and that I had not seen, and could not see, that obviously everything was just as it was, already perfect, without substance or meaning or separation, stunningly, wondrously just this, with no need for anything to be found or done. How desperate must one be to want to believe something so preposterous?!

And I understand now that we believe what we want to believe, and that we believe what we want to know to be true. We cannot possibly bring ourselves to believe anything else; we will deny unwanted truths regardless of the evidence. Our beliefs are just placeholders for what we seek to know, what we strive to reassure ourselves to be true.

And yet these hopelessly flawed beliefs drive us; they are the foundation of all of our cultural conditioning, of all the things others, as desperate to believe as we are, want us to believe to be true. They keep us, from that horrible moment in early childhood when we first had to believe — when just seeing what was true was, shatteringly, no longer enough — yoked to the cart of the ultimate belief: that things can and will be, somehow, better, and that what we do and know and believe can and will get us there.

It doesn’t matter that none of these beliefs is true.

So now I want to believe that nothing matters, and that maybe at some point this wretched self, old, now, and so tired of searching, will just fall away, and it will be seen — though not by ‘me’ — that there never was a ‘me’; that all this worry and seeking and suffering were just the useless delusions of a feverish brain. A brain that evolved, tragically, to try at any cost to make sense of everything, even when nothing made sense, and nothing needed to be done or to be made sense of. And that then it will be seen that this apparent Dave-creature is just fine — even better off — without ‘me’ to kick around any more.

But of course I want to believe this. I remain forever tethered to pursuit of the impossible truth that will finally make sense of everything, finally bring an end to the exhausting seeking. I am in a corner, now; I’ve painted myself in after a lifetime of striving to complete the picture, the picture that my latest belief denies the very existence of.

So I sit here with my box of colours, brow furrowed, wondering what this perfectly, tragically conditioned (and only apparent) creature will do next; I have no remaining illusion that ‘I’ have any agency over it (though that may be just what ‘I’ want to believe).

I want to believe that if I’m tired enough, completely exhausted, my self, this lost, scared, bewildered ‘I’ that carries with it a lifetime of questions unanswered, a lifetime of believed truths unresolved, will just let go, set me free from me. I want to believe it, but I do not.

What happens when we can no longer believe what we want to believe, when we doubt that what we believe is actually true? Perhaps we just keep painting, even knowing the picture cannot be completed, that the canvas is just a dream. Like the carpenter with only a hammer, perhaps we keep hammering even when there are no more nails, when we discover, in the endless buzz of cognitive dissonance, that there may never have been any nails. Keep hammering, what we were made to do, and taught to do, and told to do. The only thing we can do.

Since your writing pointed me towards all these “non-duality” people (apparent people) – I’ve actually found the application of the words “unconditional love” and “perfect” to “this” to be difficult to absorb. I’ve spent time suspicious of my own mind that it may be repeating other words from speakers like Tony Parsons.

I think you might be saying here that you’ve picked up a belief about “this” which is still an idea. Circuitously that’s also “this” at the same time.

I guess what might be coming out here is me thinking that a lot of the time I don’t feel that great, because work is draining and I’m not getting sleep, and I’m unfit etc. yet I can still walk a bit from my house to a stream nearby and watch the water, see a few ducks passing by and not be entirely stuck in what appears to be my mind.

I’m trying to use words to make it seem mundane – at any point it’s possible to “see” and drop out of mind, but it might not be terribly exciting or accompanied by joy either.

It’s like trying to find an almost pessimistic statement rather than latching onto “unconditional love” or “perfect”. Or you can actually feel pretty awful and still have lost sense of being a person.

Some of that may make sense…

Thanks Nathan (and thanks to those who responded to this by email). Makes lots of sense.

I was troubled for a while about how much of Tony Parsons’ evolved vocabulary has been borrowed/copied by other speakers, but my sense is that this is very difficult (ie practically impossible) to talk about coherently, and while it’s “obvious” there, it really takes almost a new language to try to convey any sense of what it is “like”. So since Tony’s been at this so long and recorded so much, he’s an obvious source for seeding this new “language”.

I also wondered if some people would try parroting what Tony and others have said in an effort perhaps to “fake it til you make it”. But to me it’s immediately obvious who’s faking it. Much easier and more lucrative ways to con people if that’s the goal.

There also seem to be lots of people for whom this is now seen (ie the sense of self has gone), but who do not seem at all inclined to talk about it. When I speak with some of them they struggle with the words but usually end up with the same kind of “more what it’s not like than what it is like” descriptions, but can’t see the point in talking about it, since there’s nothing anyone can do about it.

Tony started using the term “unconditional love” almost ironically I think, and quite a few radical non-dualists refuse to use it because it has that sense of woo-woo perpetual bliss which is not at all what is being described. Tim Cliss calls it just “this” but says you can call it whatever you want, and that unconditionality is an aspect of it. He and others say it’s important not to confuse “unconditional love” with personal/romantic love, and not to mistake it for anything blissful — it’s more a capacity (of no one) to appreciate everything equally just as it is and unconditionally. I think Tony tried to draw an analogy with the kind of love parents have for their kids, even if they don’t particularly like them; that’s still not unconditional, of course, but it kinda points more in that direction.

Dave, your post has me thinking along similar lines:

There has always been something in “me” that desires to know the “truth”, probably expecting some power to come from it—or in compensation for lack of power, to at least gain some mental satisfaction. Over many years, I have learned that “truth” is often elusive, what we imagine is true is often illusory, our mental models, thoughts, hopes and expectations are often comforting rather than realistic, and our self-conception and agency are convenient fictions maintaining a narrative illusion. Glimpses of “true consciousness” are fleeting, and suspect. And yet I continue my search for how the world works. Why try to know the “truth” if I no longer expect the information to influence reality? Apparently there doesn’t have to be a good reason, “my” self will continue its narrative and the search, as illogical and unrealistic as that may be, since the habit of thinking is so strong. Perhaps it’s a shared trance that the civilized human world is caught up in.

As a kid I too was dumbstruck at the incredible irrationality of grown ups. And how what they said too often mismatched reality. I never could rationalize cognitive dissonance away so easily, so developed an early and intense skepticism. Along with a sense of detachment that could be alienating.

I think our society is under much more stress than two generations ago, manifesting in more pathological acting out. But even in childhood I read social critics to learn or confirm ugly “open secret” realities the conventional wisdom ignored or characterized as benign. I tried to reject (not always successfully) norms I viewed as harmful, despite the social rejection that sometimes engendered.

The work world has markedly deteriorated over the last 40 years. It was never wonderful, but used to be much more tolerable, sometimes even fulfilling. Nowadays I hear the youngsters complaining about work the same way the cynical older workers did when I was a greenhorn. Although David Graeber’s books and articles explain much of today’s miserable work conditions, I think a general rise in sociopathy, excessive competition and value extraction explains a lot of the rest.