Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s book The Mushroom at the End of the World is subtitled “On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins”. She’s not talking about the future, when the industrial economy has completely collapsed. She’s talking about the present, in places where collapse is already well underway. The book describes how alternative economies — not the neat tidy ‘sharing’ economies we idealists like to write about, but the underground economies that emerge out of necessity, and always have — evolve, and the lessons they have for us as our civilization culture continues to crumble.

It’s a radical and equanimous book — it leaves judgement about economics and justice and fairness to others, and instead describes what is, in well-researched, gritty detail. To do so Anna introduces many new terms to the lexicon of economics, necessary she says because analytic, mechanical models of economics fail to describe how economies really work, so a whole new vocabulary of holistic terms is needed, terms that describe the inseparable interdependence between creatures and environments, instead of the economist’s usual oversimplified model of ‘resources’ as something separate, and mechanisms of purported control.

To show this interdependence, she describes how one tiny piece of the economy actually works — the harvesting and distribution of matsutake mushrooms. She then shows how staggeringly complex and uncontrollable the workings of this completely self-evolved and self-organized economy are, and in so doing demonstrates that every aspect of our economy works thusly — the belief that we can fully understand and ‘manage’ an economy at any level is shown to be complete hubris.

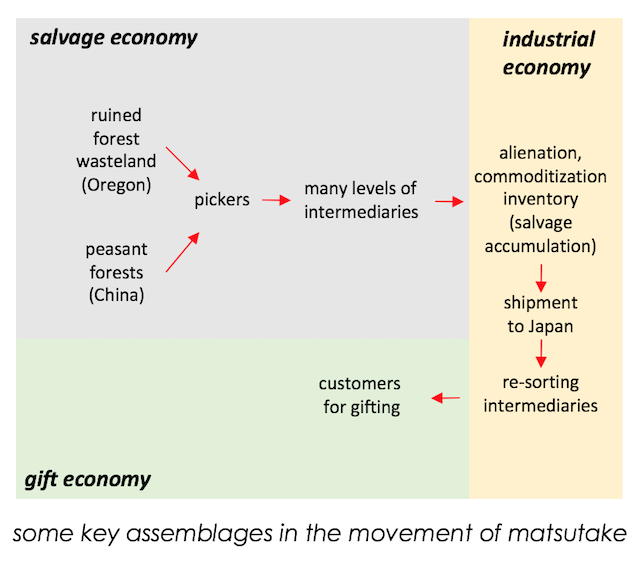

A small and totally incomplete but core part of this economy is illustrated in the diagram above. Here are its essential components:

- Like almost everything in our modern culture, the creation of wealth through matsutake mushrooms starts with a salvage operation. Salvage is the process of exploiting value outside the capitalist supply chain. Drilling for oil is salvage. Harvesting crops is salvage. Contracted labour is salvage. The capitalist economy has outsourced almost all salvage operations to independent contractors to minimize risk. Capitalists attempt to control these contractors by controlling the elements of the supply chain as it enters and leaves the industrial economy (yellow area on chart). So Chinese slave labour garment factories are bonded to multination “brand” corporations through license agreements. They don’t care what goes on in the grey “salvage economy” area — let the salvagers argue with the environmentalists, lawyers, regulators and social justice advocates. Their job is to accumulate the salvage, alienate it (make it unrecognizable as to source, as much as possible, so customers are in the dark as to what factory farming or slavery or genetic alteration or other operation was involved — hence their opposition to labelling initiatives), and commoditize it for the market — the part of the supply chain that is low-risk and under their control.

- What we read about in economics books is just what happens in the yellow area of the chart, the most insignificant part, but it’s the part where almost all profit accumulates (as required by corporate charter), and the most expensive part (where the huge oligopolistic price increases are in the supply chain).

- Much of the book describes the life and process of the matsutake pickers in the forests of Eastern Oregon, in order to convey how unfathomably complex the essential salvage economy is. Forestry policies over the years (themselves dependent on innumerable variables) have resulted in ruined forest wasteland in much of Eastern Oregon. Timber companies clear-cut much of the state, then attempted to replant monoculture tree species to keep the industry going, and eventually, due to many other factors, abandoned the effort, leaving a mess. First Nations had paid close attention to the ecology and had found sustainable ways (including controlled burning) to manage the forests (as have indigenous peasant groups in most countries with forests). But when the First Nations peoples were slaughtered and driven out, their skills were lost. The unnatural mess left behind by the timber companies creates huge fire dangers that modern fire prevention measures actually exacerbate. But it would take a century (which our civilization doesn’t have) to manage these forests back to health through knowledgable ‘disturbances’ (the term Anna uses for interventions, planned and unintentional).

- As with our modern industrial agricultural policies (what is accurately called ‘disaster agriculture’ since it uses wholesale flooding, burning, poisons and plowing to keep unnatural monocultures going), we have no idea how to ‘disturb’ ecosystems in healthy, sustainable ways, so we just keep creating monoculture messes and abandoning them when yields disappear. Creating such disturbances, carefully and modestly, is the essence, Anna says, of intervening in an ecosystem for healthy succession over decades — true permaculture.

- The ruined mess in Eastern Oregon has allowed “uneconomic” fir and pine trees to flourish, and matsutake mushrooms thrive in such forests. At the same time, Japanese forestry policies and programs (which are in turn a result of western occupation after WW2 and other complex factors) have largely eliminated firs and pines there in favour of more profitable species, accidentally killing off the matsutake, a centuries-old staple and delicacy in Japan, in the process. So suddenly, with no local supply and a new supply in Oregon, a new economy was born in the ruined forests of Oregon, and also in the peasant forests in China and elsewhere.

- Except for a few war vets, whites are not inclined to pick mushrooms in the forest for a living. But Southeast Asians, many of them refugees to the western US from the Vietnam war and other American wars, are skilled at picking them, and delighted for an alternative to the discrimination and soulless labour in American cities, so they flocked to the freedom of the Oregon forests, creating entire communities along the ethnic lines (Lao, Khmer etc) they grew up with, in the forest.

- In the Oregon forests, they ran up against forest authorities, but have now reached an uneasy peace with these authorities. Legislation, Anna explains, requires “public forests” to be thinned for fire protection for one mile around all private structures, mandates the hiring of private companies to do the thinning, and allows logging but not mushroom picking in these “public forests”. The authorities have to work around these unwieldy and absurd laws. (You can be sure the anti-environment, pro-privatization Trump will make this situation unimaginably worse).

- Impromptu supply chains then emerged to connect the pickers with Japanese companies looking to sell to their domestic clients. Buyers, sorters, aggregators and other intermediaries evolved, again mostly along traditional ethnic lines according to the specialized skills needed. Japanese import companies, many of them based in Vancouver BC, were ready to alienate the new product and accumulate the salvage.

- Once in Japan, the mushrooms are re-sorted, because one of their primary uses in Japan represents an exit again from the industrial economy. Matsutake mushrooms are prized as gifts given in an economy built on relationships. They cement deals, honour rituals and provide tokens of appreciation. Gifts of this sort were once hand-made, rather than dependent on the industrial economy. With the collapse of the industrial economy, which now simply concentrates wealth and power without adding any value (affixing a label and marketing do not add real value), we will have to learn to hand-make, or hand-grow, our gifts again.

The industrial economy, Anna explains, is unable to deal with limits. It requires an endless supply of controllable, manageable ‘resources’ and endless growth. As we reach the limits to growth, the corporations in the oligopolistic industrial economy have scrambled to outsource what they cannot control, and they use their control of supply chains to bottleneck the salvage and the gift economy so they are forced to deal with, and through, the oligopolies (despite their massive cost).

One of the key concepts of the book is the idea of precarity — the reality that ‘natural’ resources and events are unpredictable and uncontrollable and can be disruptive.

“Precarity once seemed the fate of the less fortunate”, she writes. “Now it seems that all of our lives are precarious, even when for the moment our pockets are lined.” The hallmark of a culture and world in collapse is that precarity is ubiquitous. Thanks to precarity, America cannot be “made great again”, if it ever was, despite many Americans’ nostalgia for that dream.

The economy of the future will be one of increasing precarity, leaving less and less room for the industrial economy as it grows increasingly unsustainable. We have to start imagining how this emerging post-industrial economy will emerge and how we can survive and thrive in it. That post-industrial economy will not be a knowledge economy, it will be principally a salvage economy, with elements of a gift and relationship economy. It can’t be designed or controlled. It will evolve as it must, as it always has, in patchy, unorganized and then self-organized ways. It will be one, in Anna’s words, of “disturbance-based ecologies in which many species [and cultures] sometimes live together without either harmony or conquest”. It will take more imagination than what we have shown so far (Mad Max, neo-survivalism and new old west scenarios) to collectively navigate our way to such an economy.

Such an economy cannot be imposed or centralized because it doesn’t scale. Anna explains that the industrial economy began with European plantations, where (slave) labour and (conquered) land was, for a time, unlimited and controllable. The model was then exported to the factory. Without unlimited, controllable ‘inputs’, the model comes undone, as has now happened.

The emerging salvage/gift/relationship economy will of necessity be local and opportunistic, responsive to what is available at hand. The yellow area of the chart above will gradually disappear, as we find we can no longer afford to allow capitalists to exploit their concentrated power to appropriate obscenely disproportionate wealth while doing nothing of value. As they have disintermediated, so they will be disintermediated. Imports and exports will quickly become prohibitively expensive and rare, so production and consumption will mainly occur locally, near each other. That will require much more knowledge of local ecology and sustainable ‘disturbances’ that indigenous cultures had mastered. But that knowledge and those practices are local, and will not easily translate to areas they’re most needed — areas where indigenous knowledge has long been lost.

The idea of inventorying to tie up supply and force up prices will vanish — locally it will simply not be tolerated. We will have to relearn how to accumulate only the salvage we need, and how to do so simply and sustainably. And we will rediscover the value of gifts and relationships. The concept of ‘property’ will eventually die.

In the latter part of the book, Anna talks about the increasing importance of ‘noticing’ — studying humbly how things appear to work and how small disturbances work, or don’t. She also explains how interdependent we are with other creatures. For example, pine wilt nematodes, which co-evolved with pines in North America and which take out only sickly trees (healthy trees are immune), traveled with American pines shipped to Japan in the last century. Japanese pines have no immunity and hence were devastated by these insects, contributing to the scarcity of matsutake mushrooms in Japan and the explosion of matsutake picking in North America.

Nature selects relationships, rather than species, she asserts. Survival of the fittest entails how one fits in with one’s fellow species in each local place, and that’s more about relationships with other creatures (what one offers to the whole) than competitive advantage. These in turn are the result of what she calls “contingencies of encounter”, and these occur incessantly and need to be observed and appreciated in order to thrive in any local environment.

She also speculates that, based on some recent research, viruses may be the means by which DNA try out variations to see if they are naturally selected; they may not merely be ‘random’.

There is no such thing as a separate culture, she argues — creatures of different species and their environments “co-culture” each other as much or more than creatures of a single species do. Cats and dogs and even creatures in industrial confined animal operations are our co-cultures; the creatures in such operations create a human culture of enduring wilful ignorance, denial and indifference to suffering that permeates far more than just what we choose to eat.

So rather than studying cultures in isolation, we should be studying assemblages — the contingent, precarious, endlessly disturbed, coalescing “polyphonic performances of living”.

But we seem a long way from doing that, she concludes. Near the end of the book she describes the modern Japanese phenomenon of hikikomori: “a young person, usually a teenaged boy, who shuts himself in his room and refuses face-to-face contact. Hikikomori live through electronic media. They isolate themselves through engagement in a world of images that leaves them free from embodied sociality — and mired in a self-made prison. They capture the nightmare of urban anomie for many; there is a little bit of hikikomori in all of us.”

This book is an excellent summary of where, in our economic, social and ecological theories and practices, we have gone wrong, and how we might start to learn to notice what is actually happening, and then, humbly, take our place in the world.

Love to borrow that if you have a hard copy.

Great overview. Thanks. There is so much powerful writing coming from women particularly a growing number of young native women offerring startling perspectives that are rattling this old white guy. As a companion piece this fits very well http://gutsmagazine.ca/wastelands/ by Erica Violet Lee