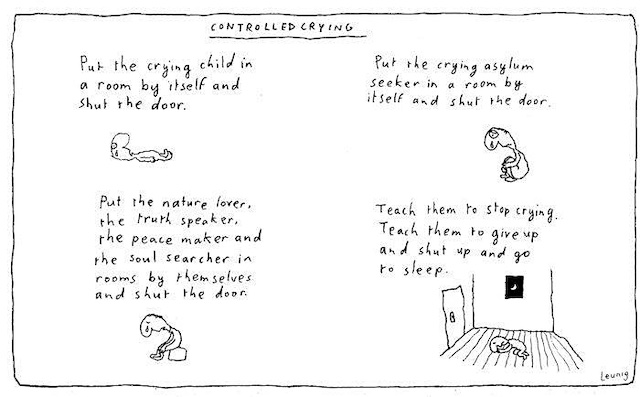

My favourite Michael Leunig cartoon, and one of his darkest.

Just about all living species, it seems, feel fear, rage, and grief. These biologically and culturally conditioned emotional responses serve important evolutionary purposes. They are all emotions of the moment — they don’t endure, and pass quickly when the cause of the distress has past.

Studies on rats and other creatures have indicated that when the cause of the distress is chronic, the creature, and often its entire group, tribe, or flock, become dysfunctional — they are no longer a ‘fit’ for where they are, and it is time to flee, shut down, and stop procreating. The alphas will hoard, so that at least a few will survive the crisis, and the others will cease eating, or, if things get bad enough, eat their own young. And if the problem is excess numbers or lack of diversity, opportunistic diseases will come in to cull the herd. Nature imposes these extreme solutions only as a last resort, when other more gentle, autonomic, moderating instincts have failed to rebalance the ecosystem.

We are at this stage in human civilization, and nature, who always bats last, is now pulling out all the stops.

But there is something unique going on with our uniquely intelligent and fierce species. A few millennia of chronic stress has led to the evolution of new conditioned emotions in humans that, I believe, creatures of the the more-than-human world do not feel. Endless fear has produced in us chronic anxiety. Endless grief has produced chronic shame, guilt, longing, despair and depression. And endless rage has produced chronic envy, jealousy, and hatred.

These are not natural emotions. They require an environment of abnormal and continuous stress, and they require cultivating, sustained conditioning, modelling, encouraging, and reinforcing. We have to learn to hate. Wild creatures will explode with rage and anger, but they will not hate. That takes a capacity for abstraction and judgement they don’t have.

But when others of our species tell us, through stories and ‘news’ reports and TV dramas and movies, from an early age, how certain identified ‘others’ are deliberately and wilfully cruel, evil, and/or dangerously insane, then we’ll be conditioned to hate these ‘others’, even if we’ve never met them.

And we have to hate in order to kill, threaten, injure, harm, or incarcerate another creature other than in the immediate passion of a rage-filled moment. We have to hate in order to prepare and plan and organize to do these things. And yet hate is completely unnatural, and it has to be carefully and steadfastly sustained or it dissipates.

I’m not preaching here — I’ve done my share of hating and hate-mongering, even in recent years when I’ve started to learn the pointlessness of it. Even my blog posts in the earlier years of writing it were tinged with hate: Hatred of climate-deniers and oil executives, of violent and self-righteous right-wingers, and of mega-polluters and producers of junk, just for a start. Some of my rants have been almost legendary.

Like others, I was also guilty of hating completely abstract things, like nations, corporations, governments and organizations, and still often fall into that trap. Hatred of abstractions can never heal the way hatred of an individual can, by addressing that animosity head-on with the object of one’s animosity and mutually discharging it. In that sense abstract hatred is more dangerous than personal hatred. It’s deranged. It’s unhealthy. It’s useless. That’s true even if, as is often the case, that hatred is mutual among members of the ‘other’ group towards you and your group or community.

That’s where it starts — when those in self-identifying communities identify and foster hatred of identified, labelled outsiders for something real or imagined that one or more of the ‘other’ group has done to one or more of ‘ours’. It can lead to life-long and irrational resentment and loathing, and to vendettas and other violence that is self-perpetuating and inculcated in future generations.

My sense is that we are capable of this hatred solely because we have accepted the ubiquitous, conditioned illusion that we are separate individuals, apart from the rest of life on earth and its environment, and that we are in charge of, in control over, and responsible for these bodies we presume to inhabit. I think the reason that even other large-brained creatures exhibit rage and fear but not hate, is that they lack this illusory sense of self and separation. But that’s a conversation for another day.

Rhyd Wildermuth just wrote a remarkable essay called Human Shields and Imagined Communities, which explores two aspects of this unique and, I think, distressing human proclivity.

The first part of his essay is about the strategy of haters (in war, in protest, and in other contexts) to deliberately provoke a violent, terrifying and excessive response from ‘the other’ in order to stir up further hatred and blood-fury among their ‘own’ community.

He talks about how the despicable military tactic of using civilians as human shields (as the US-advised Ukrainian army have been doing against the Russians, and as Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Taliban have also done extensively). This tactic has also been used, Rhyd says (and he was there), by the Black Bloc against the cops during the Black Lives Matter protests.

“Especially in countries occupied by a more powerful foreign military, resistance usually requires operating from non-military buildings.” And likewise, in areas controlled by more heavily armed enemy combatants, like the new US paramilitary police forces, resistance requires hiding among other opponents and drawing them into the line of fire through violent actions, to be able to say “See — told you they were crazy violent”.

This is not of course to condone the behaviour of occupying military forces and racist, xenophobic police, security forces, and incarceration authorities. But it’s a staggeringly effective way to amplify existing fear, rage and distrust and harden it into hatred. As Rhyd puts it:

There’s a psychological strategy in this use of human shields and civilian buildings. When a school or a hospital gets blown up, the aggressor looks really, really bad. When images and videos of children with missing limbs or old women with charred skin start circulating throughout the world, it gets harder for the military who caused those acts to claim to be reasonable or have a justified grievance.

The propaganda coup won by such events isn’t just external, however. Civilian casualties tend to work very well in the favor of the defending military as well. Every time Israel sends a retaliatory rocket into Palestinian territory and kills innocents, more Palestinians are radicalized to fight Israel. The US invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq followed this same pattern, turning the local populace even more against the US each time an innocent kid was killed in an attempt against a resistance leader.

That’s why Ukraine is doing this, though they deny completely the details of the Amnesty report.

The use of human shields isn’t the only such tactic; “scorched earth” is another.

The second part of Rhyd’s essay refers to the stirring up of the “false collective consciousness” of “imagined communities”.

Once you’ve been persuaded, perhaps drawing on your very human proclivity to hate when persuaded by a blood-curdling (true or false) story, to identify yourself with a particular partisan community in opposition to another, your collective imagined community can become what’s called an egregore, a conjured-up idea (often an antipathy) that “becomes an autonomous entity with the power to influence. A group with a common purpose like a family, a club, a political party, a church, or a country can create an egregore, for better or worse depending upon the type of thought that created it”. Perhaps “boogeyman” is a more familiar term for this.

Much of our identity politics, he argues, is about creating these false us/them distinctions and then using them, through falsely-created “communities” (‘you’re with us, or you’re with them, which is it?’) as hate-fuelled weapons to attack the “other” side.

Before you know it, you’ve put a yellow and blue flag on your lawn. Before you know it, you’re suddenly terrified of China and softening to the idea of military action against its people. Before you know it, your pacifism has evaporated and you’re ready to take up arms against some imagined community that doesn’t even exist, to defend or revenge your imagined community that doesn’t even exist. Rhyd writes:

To fight for an actual community that is being threatened—your family, your friends, your neighbors—seems to be a very human thing. I’d fight to the last breath for my husband, my sisters, my nephews, and my friends, and I think most of you would all say the same thing. But I’ll be honest: I cannot think of a single abstract concept or imagined community worth risking anything for.

That is why putting civilians in harm’s way, why using residences, hospitals, and schools as military bases is a brilliant and horrible tactic. It’s how you might be able to turn a pacifist like me into a raging nationalist hell bent on sacrificing myself and strangers to avenge someone I love.

That is why the military of Ukraine is doing it.

And to take this all out of Ukraine for a moment, it seems to me that this was exactly the point of Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. Just like the spoiled little middle class American brat throwing a bottle at the police is meant to trigger a hoped-for aggressive reaction that will turn the crowd against the police, her visit there feels calculated to have turned public opinion against China. I highly expect anti-Asian sentiment in the US to increase, and maybe we’ll soon hear beating of war drums.

We are now discovering just how effective propaganda, censorship, mis- and disinformation is at creating imagined communities and false collective consciousness. And hatred is the bedrock on which it is built.

Eastern Europe and Russia have a deep-seated hatred of each other that dates back to the atrocities of the Stalinist era and the ghastly years of the Great Depression. It was child’s play stirring it up, and in so doing bringing us to the precipice, again, of nuclear war.

Hatred, I think, is our species’ Achilles’ heel. What a hellish world it would be if it were common among other species. Fortunately, the more-than-human world seems ill-disposed to hate. Rhyd asks:

I think the forest asks a different question that humans don’t know how to ask any longer: at what point do you just live? At what point do all the ideas humans have about what is just and righteous stop and life itself takes over? And when do we finally choose to nurture, shelter, and grow the life around us rather than destroy everything at hand for someone else’s imagining?

Rhyd concludes he doesn’t know how to answer that question.

And neither do I.

Very insightful essay. The cartoon is perfectly in synch too.

Rhyd Wildermuth offers his two cents on hatred. He says much the same thing I do above, about it being a uniquely human quality and a necessary precondition for almost all human violence. But we disagree on the matter of choice. Rhyd continues to believe we have the choice about whether or not to hate, or to allow the conditioning that leads to hatred. As you know if you read this blog much, I don’t think we have any choice about it at all.