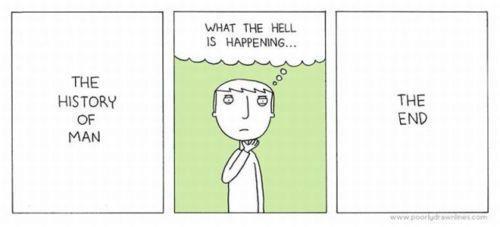

Cartoon from poorlydrawnlines.

Tell me the true story, about the time when that man

Took you in to lend a hand, and how you took him for a spin

And that money you saved you stole from him…

Tell me the true story, of how you yelled at your Mom and Dad

Left home with all you had

And now you’re running scared, and you’re mad.

— True Story, by the Small Glories

Two years ago I wrote (for the nth time) about stories. That time it was trying to deconstruct my own story — the old Story of Me I had built up over a lifetime that was designed to give meaning and coherence to my life and to provide a hint of how I might be of use to others. That’s what we do when we tell our stories. With friends we tell stories about what apparently happened, what we thought, how we felt, to use them as a sounding board for making sense of what happened, to fit it into our Story of Me. With casual acquaintances we tell stories about what we do or did “for a living”, usually in the hope that may lead to a connection, professional or personal.

Often good stories are prompted by good questions. But what exactly is a good story? And what is a “true” story? To me a good story, like any piece of good art, has seven essential qualities: (1) it gives pleasure, (2) it provides some fresh understanding, (3) every sentence in it counts (no padding), (4) it takes a camera or “theatre” view (says what was said and what objectively happened without any interpretation or judgement), (5) it respects the audience’s intelligence (no manipulation or deliberate obscurity), (6) it leaves space for the audience (to fill in their own details), and (7) it must be in some way really imaginative, clever, or novel.

I think what makes for a “true” story is element (4) — just describing what happened factually and letting the listener decide how to interpret it. Great songs (like the one excerpted above), or like this one, and great poetry, tend to be “true” stories, not cluttered with the writer’s self-absorbed reflections on what they thought or felt.

Why is this? Perhaps because it’s hard to relate to another person’s thoughts and feelings, but easy to follow and visualize and emotionally react to the events of a story. The facts are necessarily “authentic” in a way that the processed thoughts and feelings of a narrator can never be. So great songs convey the feeling in their tone, their melodies and harmonies, and great creative writing does so through its tone, the images it invokes and the perceptive adjectives it uses.

And then, the icing on the cake that rescues the song or writing from being just an observant tone poem or banal self-indulgence, is this: Some understanding can be conveyed by what the “camera view” of the teller focuses on, and by the clever juxtaposition or turn of phrase that helps you see something you couldn’t see before. In the song True Story it’s the realization that most of our stories aren’t really true, and hence are shallow, and that self-honesty and authenticity can create powerful (and necessary, if the relationship is to last) connection. In the song True North it’s the juxtaposition of constant change with the unchanging, and the realization that life consists of a balance of both. Of course, if the songwriters had written the two sentences I just wrote, their songs would have been terrible. The songwriters conveyed these important understandings through telling the stories, with a just a hint (in the song titles, in the harmonic resolution of the final notes of the choruses) that gently steers you to the understanding. (A lot of stories also contain three verses that lead you in a particular direction.) Great stories mustn’t hit you over the head (à la Aesop’s Fables “morals”) or manipulate you (eg a certain Supreme Court nominee’s fake tears and righteous privileged white male indignation).

In short, if you want to be a great story-teller, don’t tell me what you think (or thought), or feel (or felt), or believe (or learned), or what you think I should think, or feel, or believe. Tell me what happened, full of facts about what was said and done, and imagery and sensory information so that I can imagine myself there, and let me decide how that feels and what I would think. That’s a good story.

There is a great tendency (especially, it seems, in males) to try to ‘helpfully’ convey one’s own synthesis of understanding, rather than telling a story that leads to the same understanding. A synthesis is of necessity a sense-making, a judgement, and something of an oversimplification. As a result, it’s suspect. That’s why great presentations use stories (sometimes a single anecdote is enough), and why the most brilliant syntheses, no matter how often restated and no matter how cleverly articulated, are not memorable. They can be really interesting (many of my most-read articles, and some of the most popular works of non-fiction, consist of lists, often of the “how to” variety; these are all of necessity writers’ syntheses). But we intuitively don’t tend to trust them, and without a story they are almost invariably not specific or rich enough to be truly actionable.

Sadly, few stories meet the seven criteria above. It takes a mix of talents (imaginative, creative, compositional, perceptual and synthetic) to write a great story. I was amazed at how different (and more difficult) it was writing a play compared to writing a short story with a narrator, even though I always try to avoid “thought balloons” and “he felt…” passages in my fiction).

What happens if we strip away our thoughts (including syntheses) and feelings (including judgements and suppositions) from our stories? Two years ago, I deconstructed my self-aggrandizing Story of Me (everything I had supposedly accomplished, which was a self-assessment) and replaced it with a “humbler” supposedly less-dualistic Story of Me. But I now realize the replacement was just as judgemental as (just more self-deprecating than) the original. And just as dualistic.

Here’s something perhaps closer to a “true” story of me:

There is no ‘me’. The illusion of a ‘me’ within this character emerged at about age 6 and has been around ever since. It has never been comfortable in the seemingly-fraudulent, inauthentic role of Dave the Person, but as the chemistry of this body has changed and the stresses to ‘perform’ have eased, the illusory ‘me’ has been less depressed, though it is still almost as anxious and fearful and prone to escapism. Falling in love has provided powerful but only temporary respite.

That’s it. It meets almost none of the criteria of a good story. It’s neither interesting nor useful. By itself it is not a “true” story either, though I think I could construct (a much longer) one that would say essentially the same thing without the judgements and self-perceptions. But there would be no purpose in doing so. It would be a bad, true story.

Recently I attended a meeting of young entrepreneurs, faithfully telling the old “untrue” Story of Me and earnestly offering advice and reassurance. What compelled me to attend this meeting? The answer, of course, is that ‘I’ had and have no choice. Forty years of conditioning is well-nigh impossible to break. It shows that ‘I’ am holding on for dear life. Tomorrow, ‘I’ will go to several volunteer meetings and be deeply, momentarily engaged, even though there is no ‘me’ and even though nothing really matters.

And then ‘I’ will come home and start on another blog post, as ‘I’ can’t not write. It’s how ‘I’ have been conditioned to make sense of (and remember) things, and to express what ‘I’ have no other avenue to express.

Hopefully my conditioning, which seems to be gradually shifting, will increasingly see me writing stories that are (by the above criteria) both good and true. But I wouldn’t bank on it. Hopefully, over time, my conditioning will lead me to let go of the old Story of Me and to stop telling stories — both to myself and to others — that are neither good nor true.

But in the meantime — sorry, I’m doing my best and it’s all I can do. Lost and scared, ‘I’ am.

True story.

Several features of your ‘True Story’ resonated. As the author of many planetarium shows, both for the public and for students, as well as a columnist, I found myself moving away from shows that had the ‘elegant narrator’ telling people interesting things to creating characters who had a story to tell.

Eventually I concluded that almost all learning is achieved through narrative. Even if you give me a table of facts and data, I will not absorb them until I have somehow integrated all of that into my personal narrative.

What this meant was that I have wondered what makes a good story. Fortunately for me, there is lots of literature on the subject. Potential screenwriters and novelist will find articles, books, and computer programs, all based on various understandings of what makes a good story. I see a distinction between a tale, which is a series of interesting anecdotes, and a drama, which has one or more story arcs that always has someone confront some difficult issue and either succeed or fail to overcome. If it engages the reader or viewer, it is because it provokes some empathy, and the consumer learns something from the transformation in the drama (not necessarily what the author of the drama intended). I’ve enjoyed playing with early forms of the computer program, Dramatica, http://dramatica.com/theory, which is a complete theory of story. There are several other books and programs meant to help the writer. This all may seem to reduce ‘story’ to a formula — so much so that sometimes I can predict what to expect in a movie that I’m watching. That usually make me feel manipulated, and from that point there will be no empathy. I find that it does help to know something of why a story works, and what elements could be considered that might be overlooked by an author.

When I was a show producer and planetarium director, a favourite interview question posed to me was, “How do you balance education and entertainment in your shows?” What that question reveals is that our educational system is so terrible that students learn that education and learning is a painful process. What I discovered is that everyone is a sponge eager to soak up new information and perspectives that we can integrate into our lives. The most entertaining thing I could put into my shows was some information that folks had not heard before that could inform their person philosophy, or present something they thought they knew but now saw in a new light. Sure, I wrote scenes that were entertaining, sometimes with loud sound effects, music and lots of visual flash, and some people loved it. But I knew those were not the memorable parts of my shows. Often the act of researching and writing a show or article resulted in my own transformation.

Thank-you for your list of what make a good story. Here is another list that I refer to frequently.

This is what Kurt Vonnegut wrote in the Introduction to Bagombo Snuff Box.

____________________________________________________

Now lend me your ears. Here is Creative Writing 101

1. Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

2. Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

3. Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

4. Every sentence must do one of two things — reveal character or advance the action.

5. Start as close to the end as possible.

6. Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them — in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

7. Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

8. Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To heck with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

____________________________________________________

He elaborates.

– The person he calls the greatest American short story writer of his generation, Flannery O’Conner (1925 ‹ 1964) broke all but rule #1.

– The reason for rule #8 is so the reader can play along.

– Kurt writes for his late sister, Allie.

– He guesses the reason that a reader likes a story written for just one person is that “the reader can sense… without knowing it, that the story has boundaries like a playing field.” This allows the reader to be on the sidelines, watching the game, and knowing what the rules are, and when a victory is scored.

Kurt concludes the Introduction with:

____________________________________________________

The boundaries to the playing fields of my short stories, and my novels, too, were once the boundaries of the soul of my only sister. She lives on that way.

Amen.

________________________

Awesome. Thanks Robert!