my synopsis of the some of the elements that might comprise one’s Ikigai; any misunderstandings about ikigai here are mine

my synopsis of the some of the elements that might comprise one’s Ikigai; any misunderstandings about ikigai here are mine

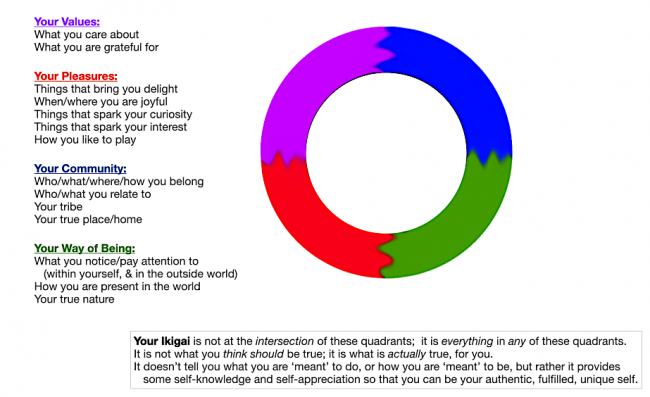

I‘ve written before about the ancient Japanese concept and philosophy of ikigai. Contrary to business consultants’ perverse and simplistic misappropriation of the concept, ikigai has absolutely nothing to do with “the work you’re meant to do”, or “finding your purpose”, or in fact about anything aspirational.

It is, rather, about the lifelong discovery, appreciation and acceptance of who you really are, now, authentically, as gauged by what gives you joy, what you care about, and what is in your true nature.

I listed what I currently consider to be my personal ikigai in my first post on the subject. Who I am, really, is a lost, scared, bewildered, and rather lazy human who has been fortunate enough to be able to engage, more and more, in quiet, creative, playful and hedonistic activities in beautiful, peaceful places, alone or with small groups of intelligent, curious, gentle people.

That might seem rather self-centred, and not of much service to the rest of the world, but my younger-days aspirations to make the world a better place seem to have dissipated. I am content, even driven, these days, to chronicle the accelerating collapse of our civilization and the ruin it is invoking on our planet, and speculate on how and why that has come to be. Perhaps I may yet find some activity that will reengage my energies and reconnect me to the more-than-human world from which I have become untethered. Something worth dying for, even. It’s not unimaginable.

My sense from studying indigenous and non-human cultures is that almost all creatures, including our bonobo cousins and even the first humans, have always intuitively sought to live in balance with the rest of life on earth. That of course makes Darwinian sense, and our disconnection from the more-than-human world might explain why the human species no longer attempts to live in such balance, and has as a result unwittingly precipitated the sixth great extinction of life on our planet.

What, I wondered, might our collective ikigai be, as a species, and as members of tribes, communities and federations?

I concluded that our ikigai wouldn’t include ‘being in love’, nationalism, or acquiring stuff. These are things that wild creatures don’t care about, and that’s not because they’re insensate or less present in the world than we are. Our human preoccupation with ‘personal’ love, with country, and with our possessions is a sign, I think, of our mental illness, our Civilization Disease. These are preoccupations born of disconnection and of fear.

To try to figure out what our collective human ikigai might be if we were somehow freed of Civilization Disease, I have been looking at some studies of non-human societies, and asking myself:

- What is it that wild creatures most love about being alive and about ‘getting up’ each day? What brings them joy, what do they collectively care about?

- When, and where, and doing what, are they happiest? What is their true nature, and what do they pay attention to?

- How do they somehow sense that their lives are part of, and at least partly in service to, some greater whole?

The dogs and cats I have known, and the birds that I’ve studied, seem to spend much of their lives (at least when they’re not under stress) in one of two states: equanimity, and, when there’s something new and interesting in their purview, excitement.

In times of equanimity they sleep, groom themselves and each other, and just hang out together. They seem very happy “doing nothing” except noticing, socializing, and (I would guess) appreciating and accepting just being a part of everything that is. They seem to see the world with a sense of endless wonder.

In moments of excitement they play, they explore, and they tend their young and others in their ‘tribe’. They seem to enjoy doing these things, too, though the tending of their young can clearly be exhausting. Even finding food, except in the rare and stressful times and places of scarcity, seems pleasurable, not ‘work’ as we would describe it.

In short, one might say, the ikigai of a cat is to be a cat, and the collective ikigai of a flock of birds is to do those equanimous and excited (and occasionally stressful) things that flocks of birds do together, like gathering noisily in staging areas every evening and flying together to an overnight roost of thousands of their kind, for no other apparent reason than the sheer social joy of doing it.

My sense is that our modern human ‘civilized’ lives are so filled with stress and unnecessary scarcity that we can hardly relate to such a way of just being. We’ve almost never, at least since infancy or early childhood, had the opportunity to just be, moving between states of observant equanimity and curious excitement.

bonobo photo from wikimedia by Nick Hobgood, CC-BY-SA 3.0

Yet that is, I think, our essential nature. We are not so different from crows. We are not (biologically) meant to live this way, in lives of constant stress and struggle, doing ‘work’ for other people, hoping that tomorrow will be better or at least not worse. We are not meant (biologically) to live surrounded by people we don’t know or trust, crowded together and clueless about how to tend for ourselves, and hence dependent on others far away to provide us with we what we need (if we can even ‘afford’ it). We are not meant (biologically) to struggle to find purpose in, and meaning to, our lives, or to live much of our lives suffering from illnesses caused by chronic stress and poor diets.

And we are not (biologically) meant to wreak such cancer-like havoc on the rest of life on earth, and on our ecosystems. “Survival of the fittest” does not mean survival of the strongest and most ruthless, it means survival of those who best fit within the ecosystems they are a part of and co-evolve with. How and why our species lost the essential connectedness with the rest of life on earth that informs that ‘fit-ness’, is a subject that never ceases to fascinate me. How could such a seemingly intelligent species become such a plague upon the planet? I have blamed the evolution, in humans, of the idea of a separate, vulnerable self for the malaise of Civilization Disease, but I’m not entirely happy with this explanation.

Wolfi Landstreicher, in a quote I have used often on this blog, says that our civilized, self-domesticated way of being is unnatural and abhorrent:

In a very general way, we know what we want. We want to live as wild, free beings in a world of wild, free beings. The humiliation of having to follow rules, of having to sell our lives away to buy survival, of seeing our usurped desires transformed into abstractions and images in order to sell us commodities fills us with rage. How long will we put up with this misery? We want to make this world into a place where our desires can be immediately realized, not just sporadically, but normally. We want to re-eroticize our lives. We want to live not in a dead world of resources, but in a living world of free wild lovers. We need to start exploring the extent to which we are capable of living these dreams in the present without isolating ourselves. This will give us a clearer understanding of the domination of civilization over our lives, an understanding which will allow us to fight domestication more intensely and so expand the extent to which we can live wildly.

I don’t share Wolfi’s optimism that rediscovering our natural way of being is as simple as putting our minds to it, but I think his diagnosis is pretty accurate. He is talking about living the way bonobos and crows and other wild creatures now live and have always lived. Why should this be so impossible for our species?

Part of me wants to accept our fucked-up human situation with its endemic Civilization Disease and disastrous trajectory as the only thing that could have happened with a species as strange and terrible (but also so ordinary) as ours. Its collective ikigai might be something like:

We care, to the point of preoccupation, about our own happiness and ‘fulfillment’, and, to a lesser extent, that of those we love and erroneously think we know. We take pleasure in entertainments that distract us from the reality of our imprisoned, tragic, domesticated, disconnected lives. Our ‘tribe’, the group we feel we belong with, consists of those who give us attention, appreciation and reassurance, and who confirm what we believe, which is what we want to believe whether or not it is true. Our true nature is to be obsessively protective of our selves and those we love, and to be often consumed with anxiety, shame, guilt, jealousy, and other reactive emotions that reflect our regrets about the past, our judgements about the present, and our fears about the future, none of which are actually warranted.

Pretty grim, huh? This is, I think, what Civilization Disease has wrought in us, and how it’s damaged us and made us all mentally ill. Still, I can understand how this has happened and how it’s made us, sadly, who we are. It’s a tragic story, but one that instils in me some compassion. This is a diagnosis of a species dying of a terminal illness, after all. We can at least offer the patient hospice.

But another part of me wants to see through our disease to humankind as it was before we went astray. What might its collective ikigai be? Maybe something like this:

We love to hang out with our tribe-mates, playing, joking, taking in this astonishingly beautiful world with a sense of curiosity and unceasing wonder. We take pleasure in exploring the unfamiliar, in learning and showing new things. We love to create things and appreciate others’ creations. We look after each other, especially the young. We are awed by, and respectful of, everything. We are amazed that everything we need to thrive is right here, in this world of seeming abundance, and somehow we are instinctively able to do just what is needed.

Yes, this could be the ikigai of bonobos, of cats and dogs and crows and most wild creatures.

But it also might be our collective ikigai, just forgotten and muddled with the onset of disease. Perhaps we have just forgotten who we really are. And perhaps, after collapse, those few humans that are left, inspired to start again, will remember.

Well, Dave, I’m gobsmacked with this post and your quest. In my 73rd year, I’m working through the same self- and cultural examinations and coming to the same conclusions.

I’m a retired anthropologist/archaeologist/museum curator, and not so retired aspiring ecological philosopher, searching for a Way to Live, mired in a culture obsessed with THE Way to Do Things. The only hope for civilization, if that’s what it is, is there’s no hope for civilization.

I’m taking some time to study your web site and writings.

Good on ya, mate!

I say to myself every morning: “If only I had started living this way 50 years ago.”

Then I reply: “I still have the rest of my life, if I live that long.”

Bonobos and everything else don’t pursue happiness or strife to live in harmony with “nature”. They just try to grab as must energy as possible within the constraints of their environment.

Our sad situation is because of our consciousness, that allows us to reflect on our predicament.

We would have been better off without that terrible gift.

We are a squarely fucked-up species.

Re-instating ourselves back into “nature” and living a so-called happy live à la Bonobo is no option. Our consciousness will ruin it for us no matter what we do.

You may be right, Ray, but I hope not. There is some evidence that, somehow, the fertility of wild species plummets under conditions of overcrowding and chronic stress. Whether that’s biological, or just some ‘cultural’ sense that this isn’t a good time to procreate, we can’t know. But, perhaps ‘thanks’ to our consciousness getting in the way, the signals/conditioning that leads to that, doesn’t seem to work for our species.