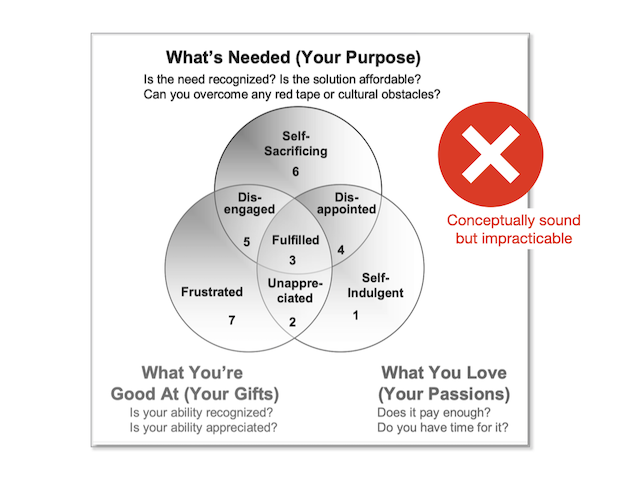

the three-circle ‘Venn model of Purpose’ from my book, designed to help you find ‘the work you’re meant to do’

Fourteen years ago, Chelsea Green published my first book, Finding the Sweet Spot, describing what I had learned advising successful small, green enterprises. The book drew on decades of experience working with about 150 such businesses, plus a lot of external research. A core message of the book grew out of an observation that the most successful small enterprises, through good times and bad, seemed to consist of people who had found their ‘sweet spot’ — work that drew upon their particular passions and sense of purpose, and enabled them to bring their unique gifts to bear. In most such organizations, the workers had complementary gifts; that is, their gifts were, one could say, mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive, so there were no ‘skill gaps’ and no stepping on each other’s toes.

When I started to apply this to my entire client portfolio, and talked with other writers about entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurs in particularly joyful organizations, this finding was confirmed again and again. There was no ‘one way’ they had stumbled into their ‘sweet spots’, but these especially successful and joyful businesspeople were undoubtedly working in them. So I was eager to share this information with the world, so others could find their own ‘sweet spots’ and hence discover ‘the work they were meant to do’.

I did the usual crazy book tour across the continent, focused especially on B Com and MBA classes and a wild mix of media outlets. Everyone seemed to almost intuitively ‘get’ the model, which is summarized in the graphic above. I was really surprised that no one seemed to have published a book or article about this earlier. But what chagrined me when I did workshops on the book was that, as easy as the model was to understand, it seemed impossible to implement effectively, either with start-ups or with established businesses looking to improve their processes.

The problem was that most people have no idea what their gifts, their purpose, or even their passions are. They simply haven’t had the time, inclination, and breadth and depth of experience doing very different things, to discover them. And they also didn’t have the empirical knowledge to see what the world needed that wasn’t already being provided by others.

In the book I profile a young couple who actually applied the ‘process’ suggested in the book to successfully start their business (which is still thriving today). But they were a very unusual pair — extremely intelligent and self-aware, introspective, curious, with an endless thirst for new knowledge and experiences (they’d just come back from a long visit to Asia to learn more about themselves and what the world needed, and what it might have to offer).

So, it would seem that my model is probably conceptually valid. Variations of it have in fact been seen by millions of people in at least three later publications by others. But it is also, I now think, impracticable for the vast majority. You can’t find your ‘sweet spot’ if you haven’t fully discovered the things you really care about, the things you’re uniquely good at, and what the world really needs. And exercises can only take you so far.

The book’s now out of print (a long story), but I still think it was interesting, and its findings important. The three very similar models that followed, all include a fourth ‘circle’ about whether what you offer is affordable to those who need it; I had tried to wrap that in as being part of the Purpose circle, to avoid the technical drawback of four-circle Venn diagrams (they can’t capture all of the possible intersections). Although my Venn diagram appears to be the earliest one published, it’s entirely likely that the four-circle models were independently derived — it’s a very intuitive idea, and someone was inevitably going to produce a model of it. Even quantum theory was independently invented by two scientists who didn’t know each other!

One of the authors of a four-circle ‘Venn model of Purpose’, labelled their model Ikigai. Ikigai is a four-hundred-year-old Japanese philosophy that has almost nothing to do with ‘finding the work you’re meant to do’, and certainly can’t be captured in a simple model. But you still see many versions of the model with this incorrect label.

When I stumbled upon Ikigai expert Nick Kemp’s article debunking the idea that the Venn model captured the essence of Ikigai, I became intrigued about what Ikigai was really about. And I was immediately excited about what I learned.

Ikigai is about the lifelong discovery of what makes your life worthwhile. It may or may not help you discover your life’s ‘purposes’, but at a more basic level it’s simply what brings you joy and inspires you to get out of bed every day.

Finding your Ikigai is, in Nick’s words, “the process of cultivating, in a self-aware manner, your inner potential, as you actively pursue what you enjoy doing in service of your family, tribe and community, via your life roles”.

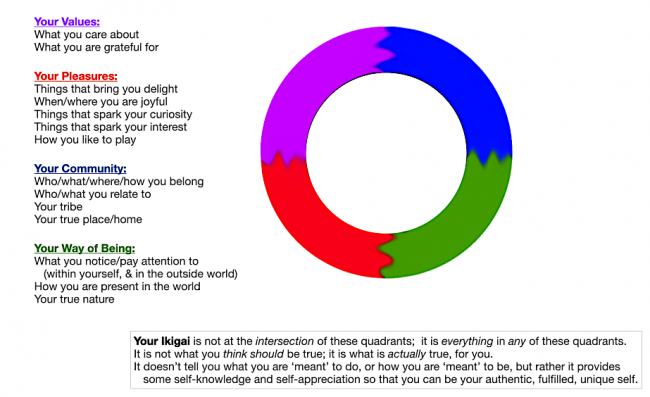

my own synopsis of the some of the elements that can comprise your Ikigai; note that any errors or misunderstandings in this graphic or article about Ikigai are mine alone — this article is unreviewed and unedited, and I apologize if I’ve got some of it ‘wrong’

The chart above is my first cut at listing some of the things that can make up your Ikigai. Unlike a Venn chart model, you are not looking for intersections or ‘sweet spots’ when thinking about this list — the entire circle, including anything in any of the four suggested categories of elements, is your Ikigai. It can be one thing or many.

It is also an attempt to see and appreciate what actually is true for you, now — so it is not aspirational, not what you wish or hope to be or do.

Ikigai requires cultivating self-knowledge and self-awareness, and one of the main ways we come to know ourselves is through getting to know other people, through our community, and discovering our difference, our uniqueness. Also, in traditional Japanese culture, the concept of service to others is important, and plays into what many in that culture likely see as their Ikigai.

We can start to find our Ikigai, Nick explains, by discovering the small things that make our lives worthwhile, the little private joys, that don’t depend on external validation or recognition. From that special first cup of coffee in the morning, to the cat that curls up on your lap whenever you sit on the sofa, it’s all Ikigai.

A related concept, Ikigai-kan, refers to the awareness of, and feelings toward, the ‘things’ that comprise our Ikigai.

I was fascinated to discover that neuroscientist Ken Mogi, who has written two popular books on Ikigai, does not believe we have free will. So for him Ikigai is about discovering how our Ikigai, in a way, plays itself out through us; it’s not about willing ourselves to be other than who we are or to do things differently. It’s about knowing and appreciating ourselves, so that we can be our authentic, fulfilled selves, free of guilt, shame and self-recrimination for not being other than who we really are.

In his Little Book of Ikigai, Ken outlines what he calls the five ‘pillars’ of Ikigai, which are guidelines for ways of living to discover and stay true to your Ikigai. They are:

- Start small — begin everything with gentle, modest steps

- Release the self — recognize and let go of the burden of the self, identity and ego

- Live in harmony and sustainability with everything around you

- Take joy in small things

- Live in the here and now — be in the flow of the present moment and focus your attention accordingly

The last chapter of the book is entitled: Accept yourself for who you really are. And finding your Ikigai can help you see and appreciate “who you really are”.

I’d love to have a chat with Ken to hear him explain how one can do these things when there’s no such thing as free will; but that’s a subject for another post.

(Ken has a new book out called The Way of Nagomi, which explores some additional characteristically-Japanese ideas and values, such as about moderation, childlike wonder, the folly of individual decision-making, the unsustainability of romantic love, the dangerous simplifications of our stories of history, and the causes of modern alienation.)

I found it illuminating to use the list in the graphic above to self-assess what some of the elements or aspects of my Ikigai might be. It’s worth mentioning that to most Japanese, one’s Ikigai is a private, and evolving, matter. I suppose that if you feel you have to censor acknowledging things that bring you joy, things you really care about, or aspects of your true nature, for fear they may be judged harshly by others, you cannot be truly honest about your Ikigai. I’ve reached the age where I no longer care much how I’m judged, so I don’t think I’ve subconsciously omitted anything from the following list, which is illustrative only, undoubtedly incomplete, and not in any particular order:

- my favourite music

- the view from my ‘terrace in the sky’ home

- tropical ocean beaches

- my tiny number of true friends

- rainforests

- my small, changing blog circles, family circles, and neighbourhood circles

- the more-than-human world

- reading and writing (in order to learn new things, not to chronicle collapse)

- my creative writing (words and music)

- play (online and board games, occasional flirtations, philosophic ideas like radical non-duality and no-free-will, clever exchanges, challenging crosswords, and collaborative creative activities)

- equanimity

- curiosity, and imagining possibilities

- clever humour and theatre

- hedonistic pleasures (eg hot baths by candlelight)

- gentle, peaceful activities, people and places

These are the things that “get me up in the morning”. Making such a list was, for me, its own reward. I learned something about myself, particularly why I seem to be in such an extraordinarily good space in my life these days, despite the chaos that the rest of the world seems to be experiencing.

It was also interesting to note what, when I was honest with myself, was not on the list, and why: no foods or drinks, no forms of exercise, little or nothing related to science, politics, economics, or even philosophy or the arts. My list might have been quite different a decade ago, when I thought so differently about so much. I think my current list is probably close to what it would have been when I was a young child.

If I have the self-discipline to maintain this list over time, it will be interesting to see how it might evolve.

One final idea that caught my attention: Moai is a Japanese term meaning “meeting for a common purpose”, and on Okinawa, it takes the form of cohorts of 5-6 people selected at an early age to support each other all through their lives, and identifying and discussing Ikigai is part of that support group’s role. I wonder if such a concept might work in the west? There is something magic about that number 5, and it’s likely not a coincidence that Okinawa has the world’s longest healthy life expectancy.

For lots more on Ikigai, check out Nick’s website and/or subscribe to his podcasts. Thanks to Nick for our conversation yesterday.