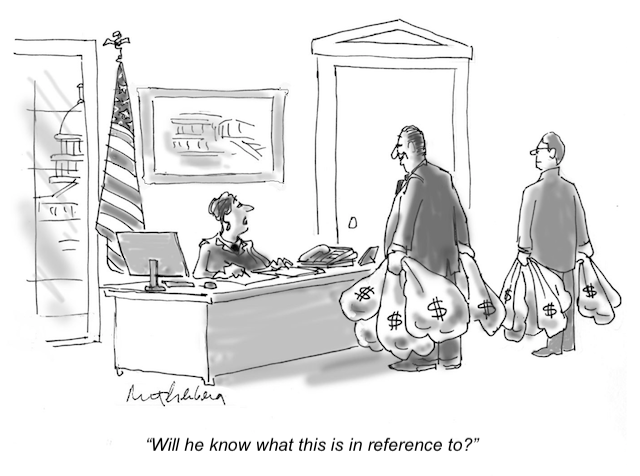

cartoon by Mort Gerberg (mortgerberg.com) in The New Yorker

I am reading Michiko Kakutani’s new book The Death of Truth, and my enduring reaction to it is, “Yeah, obviously, the idea of objective truth is being systematically undermined and mocked by those with vested interests in perpetrating lies (notably psychopathic politicians, hostile foreign governments and corporations and their toadies). That’s happened before (Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Big Tobacco, Exxon, Monsanto etc) and it’s frightening. And of course we should be exercising more critical thinking and ‘defying cynicism and resignation’ and fighting to defend democratic institutions and other victims of misinformation and disinformation campaigns. But surely we’re already doing that to the best of our ability, no?”

The book provides lots of data to support its undeniable thesis, but paradoxically its lack of practical ideas to deal with this challenge may actually exacerbate our cynicism and resignation. And in fact there are probably not any solutions to this predicament.

I’m less interested in lamenting that than in trying to understand why and how it came to be. Why are people so malleable in their thinking and in their beliefs that they would come to unthinkingly support and defend preposterous untruths?

We can blame our education system for not providing us in early years with critical thinking skills, but I am not sure the dearth of such skills is a recent phenomenon.

We can blame the faux-information media for spreading and repeating such nonsense that we no longer believe anything they or anyone else says, but this is nothing new either, and if anything the lies they disseminate today are balder and more explicitly not science-based, evidence-based, or even reality-based than was the case a generation or two ago (McCarthy Era, anyone?).

We can blame corporations and their ad-men for inuring us to lies and distortions and exaggerations perpetrated at enormous cost (passed along to us in the cost of the product) to generate more profit. But this isn’t new either (tobacco ads, anyone?).

Or we can blame social media for the global ‘amplification’ and ‘democratization’ of untruths and for creating ‘bubbles’ where the truth is, by intention, never aired. And there is no question that Russia and other hostile foreign interests relentlessly exploit the ignorance and gullibility of citizens of countries they want to undermine, and flood them with millions of inflammatory and libelous fabricated stories and spread them using millions of fake and bot identities. But to some extent we choose to belong to and partake of such ‘bubbles’, and choose to believe uncritically what is said in them. And just as we unsubscribed to printed media that stopped doing their job (when it didn’t produce enough profit), we can opt out of Facebook (which continues to defend allowing and accepting money for political ads that openly lie), Twitter and the rest of the social muck media. I know people across the political spectrum who have simply stopped using these miscreants’ platforms. And I know ignorant, massively-misinformed people who never significantly participated in social media in the first place, and who never read newspapers or news magazines either. You don’t need to go online or even to a newsstand to be misinformed and lied to.

So if none of the usual suspects is to blame, why is it so many people believe such nonsense, and as a consequence exercise those misguided beliefs whenever they vote, shop and talk with others, including their own families and others who seemingly trust their judgement — all to the detriment of our health, our environment, our democracies and global peace?

My hypothesis is simple: People don’t want to know or to believe the truth; and more than that, they don’t want to think, and they don’t want to imagine the future. The real, actual, fact-based, evidence-based truth feels bad. Thinking about what is happening, and what we are, or are not, or should be, doing about it feels helplessly, hopelessly bad. Imagining the world we are leaving for future generations feels bad.

Why would anyone aspire to believe or think or do what feels bad, when there seem to be no solutions, no hope that any of it will make a difference or make anything better?

It’s not that, in this unoriginal (it’s happened often before) time of the Death of Truth, we don’t know what to think or believe, so bombarded are we with conflicting and erroneous information masquerading as truth. It’s not that truth doesn’t exist, that it’s all a point of view (short of existential arguments, there is an enormous consensus of people who have carefully and objectively studied important issues — like climate collapse and vaccines and the value of incarceration and whether smoking and other vices are bad for your health — on what is factually and on the weight of evidence true).

It is, rather, that we can’t handle the truth. We already feel bad, and we don’t want to feel bad. Our genetic and cultural conditioning, our very human nature, is to seek pleasure and avoid pain. Why, when we’re all struggling to deal with our own personal physical, emotional and situational traumas, and struggling to provide for ourselves and our families, would we want to know or believe or think or imagine anything that would make us feel even worse?

I completely understand the mentality of those who choose to believe a Rapture will wash away all the terrible things seemingly happening in the world, who choose to believe technology or a singularity will fix (or render moot) everything wrong with us and our civilization, who choose to believe that the unstoppable crises bringing about the sixth great extinction of life on Earth are just hoaxes that will go away by themselves, or will go away if we let some demagogue apply a simplistic fix to them all, or who choose to believe it is some “other” group that is to blame for all these predicaments, and that getting rid of this “other” will solve everything.

And I completely understand the mentality of those who cannot resist the pull of addictions that, at least for a while, let them feel better, let them not have to worry or care about what is oppressing them, and what is, horrifically, true or real.

The bigger question in my mind is — what’s up with those of us who willingly reject simplistic solutions, unscientific and unsupportable beliefs, and lies designed to make us feel better or at least shift the blame? Are we truth-lovers masochists?

I can only answer for myself, of course. I am privileged to have lived relatively free from trauma and stress, to have been encouraged to think critically, and to have been endowed with a curious and creative mind and a rich imagination. This extraordinary privilege allows me to entertain and handle with some equanimity some very dark truths. This privilege has allowed me to get a lot of practice thinking critically, and imagining possibilities from the ghastly to the exquisite (since even if you have the mental faculties for these things they need constant practice or you quickly lose the capacity to exercise them).

So, while I am afraid of many things, the truth is not one of them. But in that, I am blessed; it has nothing to do with my own doings or initiatives.

That hasn’t always been the case: A significant part of my life was spent dealing with the Noonday Demon — utterly incapacitating depression. So I have considerable sympathy for those who haven’t had the privilege and blessings I have had (though sometimes I have to remind myself!). Those for whom even vaguely believable lies are often a respite from the grind of everyday misery. Those who believe the absurdities they have to believe because the alternative is just too much, too hard to handle. Those who dismiss inconvenient and uncomfortable truths and opt instead for oversimplifications, distortions and misrepresentations because it makes their unmanageable, impossible lives a little more hopeful, a little easier, a little less painful, a little more manageable.

Those for whom the Death of Truth is just an unacknowledged byproduct of the need to keep going, day by day, in a world that seems impossibly complicated, unbearably out-of-control, and getting inexorably, hopelessly worse.

https://un-denial.com/

Thanks for the thoughtful outline of The Death of Truth. You don’t indicate specifically how much is Kakutani’s and how much is yours. I suppose your contributions blend together. I’ve been chipping away at this same issue at my blog, which I refer to as an epistemological crisis. The framing you offer at the beginning is questionable. The lack of novelty of some dysfunction does not really suffice to wave it away. Longstanding problems often intensify when we deny their importance due to habituation, such as with health issues.

The hypothesis you present — that we believe what we want to believe out of discomfort with what truth or reality would require us to recognize and acknowledge — sounds a bit like one of Pollard’s Laws having to do with laziness and path of least resistance leading to rationalization and/or willful denial. If some adhere more closely to the Pleasure Principle, I suppose some few of us (me included) adhere to the Reality Principle as a matter of personal integrity.