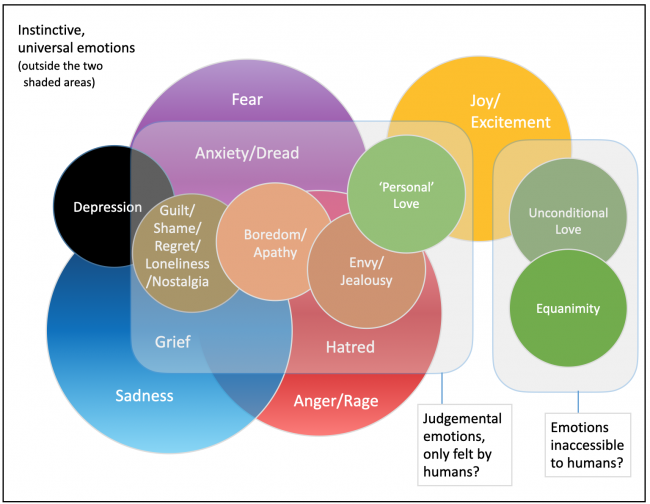

Those who have studied animals for a long time suggest that the emotional ‘landscape’ of non-human animals is different from that of humans. The ‘map’ above attempts to articulate what those differences are and how they might have arisen. It is based very roughly on emotion maps developed by educator/author Karla McLaren, but diverges substantially from her taxonomy.

My map differentiates three categories of emotions:

- Instinctive, universal emotions shared by all living creatures: Notably the ‘big 4’, Fear, Anger, Sadness, and Joy.

- ‘Judgemental’ emotions that I suspect are unique to humans: Those in the left shaded rectangle on the map, that I think require some moral judgement (or self-judgement) in order to be felt.

- ‘Natural’ emotions (in the right shaded rectangle) that I suspect are uniquely inaccessible to humans because we are biologically and culturally conditioned from birth to conceive of ourselves as ‘selves’, separate and apart from the rest of life and everything else on earth. I have argued that this sense of disconnection is the result of an evolutionary accident in the entanglement, unique to human brains, of our capacity to conceive and our capacity to perceive. The resultant confusion, which I’ve explained in my Entanglement Hypothesis posts, has created a ‘veil’ through which we see the world, which precludes us from feeling the emotions of equanimity (pure acceptance of what is, without judgement) and unconditional love. That unconditional love is very different from the ‘personal’ love that humans feel for ‘others’, which is conditional and laden with interminable judgements.

My sense (which is supported by most of the research I have read) is that wild creatures spend most of their lives in one or more of the three emotional states shown on the right side of the ‘map’ — joy/excitement, unconditional love, and equanimity. I have personally witnessed a lot of compelling evidence of animals instinctively expressing these emotions.

For wild creatures, I would argue, feelings of fear, anger/rage, and sorrow are both situational (prompted by others’ behaviours or external circumstances) and temporary. In healthy animals, in other words, these feelings are fleeting and relatively rare. The body’s reactions to these emotions are powerful and energy-diverting, to deal with the apparent crisis or danger that has given rise to them. Once the crisis has been dealt with and has passed, wild creatures, I think, return quickly to the ‘normal’ three emotional states of their existence: joy/excitement, unconditional love, and equanimity.

There is some evidence that, while wild creatures’ emotional lives are therefore ‘simpler’ than humans’, they actually feel their emotions more intensely than humans do, since their is no veil of judgement and rationalization tempering or qualifying their feelings.

The ‘judgemental’ emotions — those that require some kind of moral judgement or good/bad/causal rationalization in order to be felt — are, I believe, the crux of the problem of the human malaise and our endless dissatisfaction, suffering, and predilection to create misery for others. These emotions are, I would argue, extensions and entanglements of the three core instinctive emotions that all creatures feel under conditions of great stress: fear, anger/rage, and sorrow. They result from our brains’ obsession with ‘making meaning’ of our feelings, rather than just allowing our bodies to react to them the way wild creatures’ bodies do, in the ways that have been evolutionarily successful for billions of years. And they create a kind of inescapable feedback loop — the intellectual judgement provokes a judgemental emotion, which in turn provokes a further intellectual judgement to rationalize the feeling of that emotion, and so on.

That, combined with the fact that our species, in what we call ‘civilization’, has created a living environment in which stresses aren’t acute and temporary, but relentless and chronic, means that we spend most of our lives in a state of chronic stress and reactivity to that stress. And stress kills, in more ways than one.

Our human brains, unable to conceive differently, assume that we can ‘know’ what another person is feeling, and why they are feeling that way. It assumes that our mental models’ hopelessly simplistic assessments of truth and causality are both accurate and universally shared. This is a recipe for disaster. Not only can we not hope to ever understand what another person is feeling, or what ’caused’ that feeling, there is no one in ‘control’ of our or their feelings. We are all just acting out our conditioning, just as wild creatures do. Our judgements and assessments of the reasons (sheer evilness, insanity etc) for others’ behaviours are inevitably shallow, simplistic and fundamentally erroneous.

No surprise we are so fucked up as a species, wallowing in this chemical mass of self-reinforcing reactions and unfounded judgements for most of our lives.

The chemistry of our instinctive emotions, the ones we share with other creatures, has only recently become recently established. They are a consequence of millions of years of evolved biological conditioning. They have been essential to most creatures’ survival — though it should be noted that most of the species that have appeared on our planet are no longer with us.

We know even less about the chemistry of our judgemental, perhaps uniquely human, emotions. Even our words for these emotions are, mostly, of relatively recent vintage and very ambiguous in their meaning. The words anger and anxiety, for example, come from the same root, as do the words ire and err. The word hatred comes from a root word that originally meant sorrow, while the word sorrow comes from a root that originally meant sickness. The word guilt has no known root at all, and its history is a mystery. The words jealous and zealous once meant the same thing.

We really don’t know what is going on in our conditioned, chemically-driven bodies when fear gives way to chronic anxiety, or rage gives way to inextinguishable hatred. The former, instinctive emotions would seem to be obviously healthy and evolutionarily useful, while the latter, chronic, always-under-your-skin judgemental emotions would seem destructive (both to those feeling them and to the objects of their emotions) and inherently maladaptive and unhealthy.

That is why I believe these judgemental emotions are an evolutionary misstep. As cancers are to the physical realm, these judgemental feelings are, IMO, to the emotional realm. Good for nothing, harmful, and dangerous.

But that’s the thing about evolution: The things nature tries out, in the never-ending search for a better ‘fit’ with the environment and with other species, aren’t always good ideas. And it can take a long time (by our standards, anyway) for an evolutionary error to work its way through and be extinguished by subsequent evolutionary advances.

And I’m not saying that, were it not for these maladaptive judgemental emotions, the endgame we’re approaching for our civilization would have been any different. We are an easily-conditioned species, thanks to the suggestibility of our large and imaginative brains, our invention of abstract languages, and our understandable compulsion to band together and ‘join forces’ with others of our species. Our imaginations also magnify and amplify our capacity for violence. And we are, like many primates, a notably fierce species, ready, willing and able to kill when the opportunity arises. Our conditioning would most likely have led us to where we are even without the apparent evolutionary misstep that’s befallen our species.

So, the tragedy of our entangled brains is probably not the primary cause of the massive destruction we have unleashed on our planet.

But it is, I would argue, the primary cause of almost all of the suffering that we have, and continue to, put ourselves and our fellow humans through, as we struggle, bewildered, to try to make sense of our world, and of our feelings.

According to Temple Grandin, animals have four basic emotions… seeking, fear, panic and rage… and three special purpose emotions… lust, play and care. Based on my own experience with dogs and cats plus forty-one years of raising livestock (goats, sheep, ducks, geese and rabbits), I would add contentment, and for the more intelligent species, something that could be described as affection to Grandin’s list.

Like so many people in the modern world, I suspect that your disdain for your fellow humans has lead you to idealize other species and to project the more positive emotions (joy/excitement, unconditional love, and equanimity) onto the other species. This is not a criticism. It’s hard not to anthropomorphize other animals. Just realize that we do them no favors by doing so.

Thanks. I think your, and Temple’s, lists of wild creature emotions, map reasonably well to mine. It’s all conjecture, after all. It’s not hard not to anthropomorphize other animals, and to project onto other people as well — it’s impossible not to do so. Our own mental model of the world is all we have to go on.

I feel, as I think most people do, a great instinctive love for all creatures, human and more-than-human. It’s called biophilia, and I think it’s been evolutionarily selected for. My feeling for humans is not disdain, but rather sadness and pathos. My sense is we are a dis-eased species, suffering immensely from what I have described as a mental malaise (an entangled brain) that is unique and nearly universal in our species. Of course, that’s all conjecture, too, but it’s the only way I’ve found so far to make sense of the world.