Adam Kahane’s latest book Solving Tough Problems stresses the importance of speaking candidly and listening openly, in order to allow resolutions to complex (wicked) problems to emerge. The book is principally anecdotes of Kahane’s experiences as a facilitator of groups trying to grapple with seemingly intractable problems. What’s most interesting about these stories are the archetypes of people, roles, posturings and preconceptions they raise, which exemplify the barriers to bringing about change in organizations. He quotes one I particularly like, that I bet you’ll recognize in your own organization, or perhaps even in yourself: “I’ve worked with these senior managers for decades. They have no energy. They have turned into turnips. They don’t want to do anything. They like having excuses. They are all making big salaries and feeling no pain. They have the perfect cover for anything: Our bosses won’t let us do anything. There was a time when they had spirit, but they have been emasculated. Their spirit has been sucked out of them.”

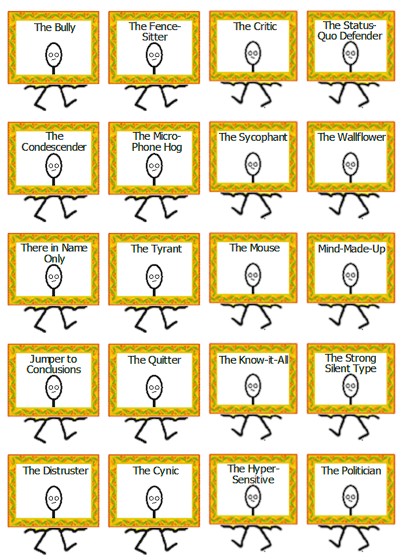

As I read through these stories and listed the negative archetypes (Kahane’s stories have lots of heroes, original and reformed, but they’re not nearly as interesting as the astonishingly recognizable negatives), I tried to organize them into groups, but I couldn’t do it. Twenty of them are listed in the diagram above, and their ‘thought clouds’ are as follows — be honest and admit how often these thoughts have gone through your own mind in meetings and other supposedly collaborative activities:

Many of these thoughts are going around in the heads of people at a lot of meetings and collaborative events. Kahane’s solution is to practice, enable and encourage more open speaking (candour) and listening (attentively, without prejudging), to prevent these dysfunctional thoughts from arising at such events, and get them on the table when they arise anyway. The Open Space approach would suggest that one critical way to do this is through crafting the invitation for such meetings appropriately, so that the right people (and a minimal number of the archetypes pictured above) show up and participate enthusiastically, with commitment, passion and responsibility, and listen intently and allow collective insights and ideas that could address the issue at hand to emerge. In an earlier article I re-told the children’s story There’s No Such Thing as a Dragon. The archetypes who bring the baggage of these dysfunctional attitudes and prejudgements to collaborative events are like a roomful of dragons, unrecognized and tacitly unnoticed by the organizers and participants. So one solution is to (politely) not invite the dragons in the first place. And, if that is done and no one then shows up, the event organizers should appreciate that potential participants have opted to avoid what they see as a meetingful of dragons, and redesign the event so that the desired participants are more enthusiastic. A second solution, also borrowed from Open Space, is to allow participants to ‘vote with their feet’ — to leave and possibly start their own conversations on the issue elsewhere if they believe they are not getting or providing value to the event (i.e. if they find too many dragons in the room, or find they are turning into dragons themselves). Kahane suggests these additional approaches to clear the dragons from the room, and get the participants working together on all cylinders:

Even when the room is dragon-free and the participants are collaborating effectively, there are still two more enormous obstacles to overcome:

No wonder, then, that it usually takes an enormous sense of shared urgency and commitment and highly skilled facilitation to create the kind of events that, like the ones in Kahane’s encouraging success stories, not only clear the room of dragons but enable the unencumbered participants to achieve remarkable results through true collaboration. |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Hi,Don’t you think every one of us are in one of the states mentioned by you at some point of time or the other. Hence everytime in a meeting we enact if not all, some of the characteristics mentioned here

I think that the extent to which we can exclude dragons from meetings is very limited. At some point, a decision needs to be implemented, and that decision should have received input and been discussed with all of those who will be affected by its implementation, otherwise there’s a risk of perverse/ineffective implementation.Excluding people who make problem-solving difficult from problem-solving seems like a rather traditional approach.

Nice exposition .. but discouraging as heck.You know pretty much what I think about HR / people mgt processes (job eval, performance mgt., competencies) and their contributions to enabling and sustaining these mindsets, under the surface. Thank goodness for tools like Open Space, although when used in many organizations it might be better called “Creating SOME Space”

Jayanth/Kal: That hasn’t been my experience (my experience has been more like Jon’s). As you become aware of the dragons I think you start to take responsibility for pointing them out, politely, to others in the room, and using the Law of Two Feet when you become a dragon yourself. When you’re young that’s harder to do — the risk is too high — but as you get older the onus is on you to do so. Problem-solving is inherently difficult, and sometimes impossible — all we can do is allow the best understanding and opportunities for action to emerge, and they can only emerge if there’s candour and openness in both speech and listening. The answer to people who make problem-solving (more) difficult is to gently show them that such behaviour is unproductive and help them become better collaborators. If it is their ideas and unique perspectives that add to the perceived complexity of the problem, rather than their attitude, then of course you don’t want to exclude them — they are not acting in any of the 20 dragon personas and are not dragons.