Many of my articles on free will and non-duality argue (perhaps obsessively) that:

All human behaviour is (no more and no less than) the biologically and culturally conditioned response of our bodies to the circumstances of the moment. There is no room for ‘free will’ in it, but while our behaviour is determined, it is not determinable, because the circumstances of the moment are utterly unpredictable. The corollary is that while we cannot ‘change ourselves’ (ie alter our own conditioning), we can be ‘changed’ (ie by others’ conditioning and by changes in the circumstances of the moment. But not in any controllable way.

I have also argued, somewhat tangentially but I think importantly, that

(1) if there is no ‘free will’, there cannot be any such thing as a real ‘self’ (that sounds backwards, but I have explained, I think, why it is a logical conclusion), and that

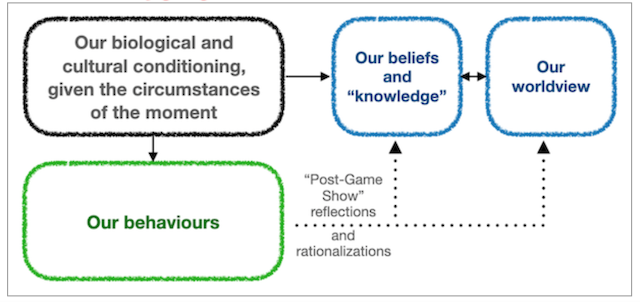

(2) it is our behaviours that in part condition our beliefs, but, counter-intuitively, our beliefs are merely an after-the-fact rationalization of our behaviours, and these beliefs have no reciprocal effect whatsoever on our behaviours.

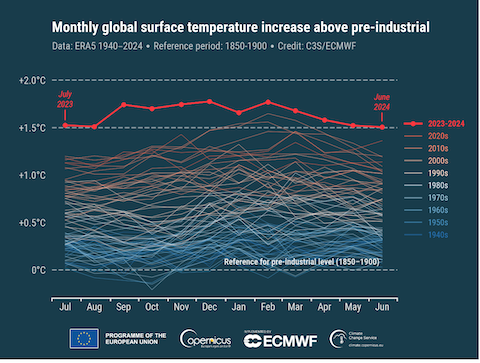

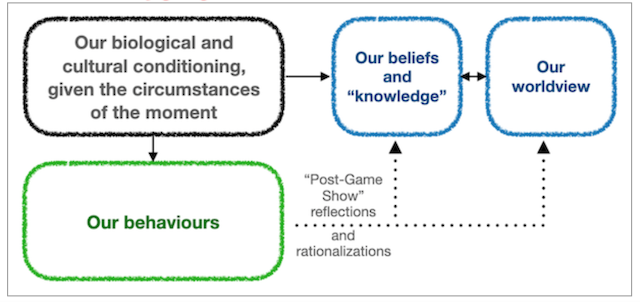

So, in terms of the chart above, the ‘domains’ of this conditioning are:

(Blue) The model our brains have conjured up to try to explain and make sense of its sensory inputs. We call that our ‘self’ (or soul, or mind, whatever fanciful term we prefer). ‘We’ are conceived to be the ‘centre’ of that model. Our beliefs and worldview constitute the ‘scaffolding’ of the model, what we (have been conditioned to) assert to be ‘real’ and ‘true’. It is an illusion, a kind of pervasive hallucination. This illusion is seemingly unique to the human animal, and it is entirely unnecessary to the successful functioning of the organism. It is, I have hypothesized, a spandrel or evolutionary misstep, something that nature evolved to ‘try it out’ to see if it might be useful to the survival of the organism, when it turns out it is not.

(Green) What we conceive to be a ‘whole’ organism, such as a human body, and what it apparently ‘does’. As Stephen J Gould & Richard Lewontin have explained, the boundaries that delineate what that organism ‘is’, from ‘everything else’, are arbitrary. It would be more accurate to say that organisms such as bodies are processes, rather than ‘things’. ‘Things’ are just labels for the constituents ‘within’ an arbitrary selected boundary, that are engaged in those processes. And behaviours, then, are the observable properties of those processes. (Not a very ‘solid’ view of reality, is it?)

(Black) The processes and emergent conditions that affect apparent organisms and affect those organisms’ processes. The processes are entirely conditioned by other processes and emergent conditions, and the emergent conditions are largely the result of these processes. Determined, but way too complex to be determinable.

The actual conditioning process — how it affects organisms — is something I took for granted biologists understood. When a human body moves to strike, or to kiss, another human body, for example, I basically assumed the conditioning actually took place at the cellular, molecular, and even atomic and sub-atomic levels, that, in some mysterious way, ‘collectively’ resulted in the conditioned behaviour.

But a recent interview sent to me by my friend Paul Heft has profoundly challenged that assumption. In it, biophysicist Denis Noble presents a very different way of interpreting what underlies what we see as the behaviour of organisms. Since Darwin’s death, a reductionist school of thought called Neo-Darwinism, championed by ideological dogmatists like Richard Dawkins, has asserted without much challenge that the behaviour of organisms is ‘bottom-up’ — driven and determined by our genes. This argument would hold that our conditioning is essentially encoded in our genes, which then drive everything we do (directly, in the case of biological conditioning, and indirectly, in the case of cultural conditioning). Subject, of course, to those pesky “circumstances of the moment” (an earthquake, a war, or a chance meeting).

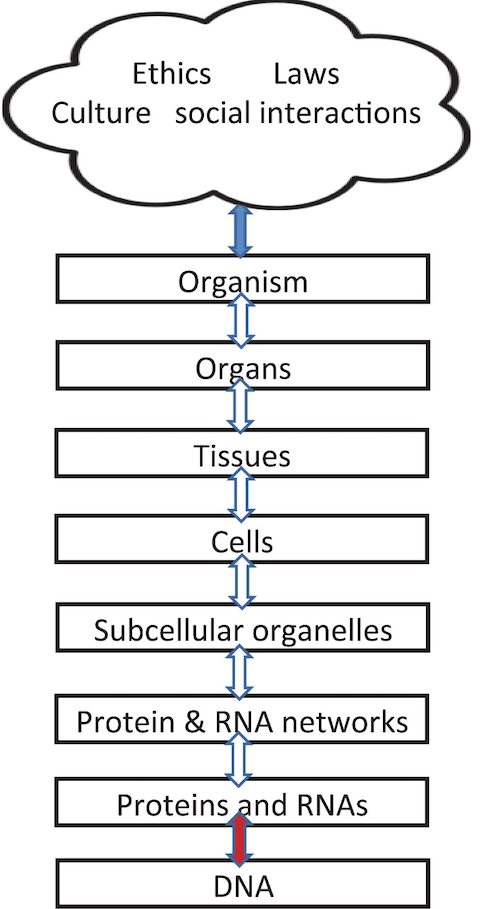

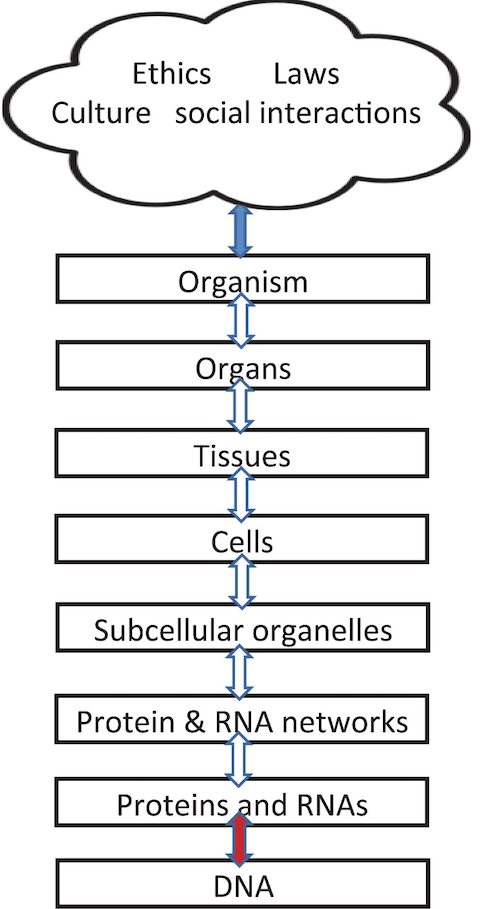

Denis argues, based on decades of investigation and study of actual biophysical processes, that the conditioning is substantially ‘top-down’ — that the ‘instructions’ for evolutionarily advantageous behaviour actually reside (ie are ‘physically encoded’) largely at the cellular and whole-organism level, and that, contrary to Neo-Darwinism, it is the cells and the organism that generally then instruct the genes and molecules and atoms how to actuate the needed behaviour.

To understand his argument, we first need to understand how science uses the terms ‘causality’ and ‘purpose’, sometimes quite differently and in a more nuanced way from how we use these terms in everyday language.

Purpose, per Denis, is “the use of chance to explore strategies for the future”. Evolution uses chance, or random variation, to explore evolutionary possibilities. This process is called the harnessing of stochasticity. Nature tries out variations and ‘selects’ those that make the organism ‘fitter’ for the environment it currently faces. One particular example of this harnessing is the evolution of photosynthesis, without which we wouldn’t exist. Evolutionary processes, he says, are purposive, not purposeful, and there’s an important difference. Here’s the Open University’s explanation of the distinction:

Two forms of behaviour in relation to purpose have also been distinguished. One is purposeful behaviour, which Checkland (1993) describes as behaviour that is willed – there is thus some sense of voluntary action. The other is purposive behaviour – behaviour to which an observer can attribute purpose.

Denis deliberately uses the term “purposive” rather than “purposeful”. When we think of something having a purpose, we think in terms of will. But Denis does not require free will for there to be purpose, which he means in the sense of “purposive”. He speaks of “purposive behaviour” and “purposive agency”, and when he says “It’s the whole that gives purpose to the parts”, he means it in the purposive sense.

We (observers) can attribute purpose, in that sense, to the “emergent qualities” of the whole (eg an organism). That doesn’t mean there is any ‘design’ or ‘innate tendency’ in the universe. In fact, Denis goes to pains to assert that he is defining purpose in scientific terms, and not at all in any “spiritualist” sense.

He provides as an example how the body’s immune system reacts to the discovery of a novel virus like CoVid-19:

- The immune system (the entire human sub-organism that responds to potential diseases) receives information that there is a novel, potentially dangerous threat to it (and to its host, though it need not even be aware of the host’s existence — this is just how the organism evolved, by natural selection).

- The immune system then instructs the genome and its molecules to ‘randomly’ create thousands of mutations to discover one that will kill the invading virus. Once the best mutation has been found, the genome is instructed to produce millions of that mutation to eradicate the virus now, and, by keeping the mutations in reserve, to kill it whenever the offending virus reappears in the future. This is how ‘natural immunity’ works.

- We as observers can attribute purpose to this amazing process — using chance (the many random mutations) to explore strategies and possibilities. But it isn’t purposeful. No directed will was exercised. It is simply purposive. It is what the immune system has evolved to do. The genes just carry out the orders.

Denis’ conclusion is that “The organism is ‘doing’ natural selection, ‘on purpose'” (purposively). By its very (evolved, massively complex) structure, “the complexity of the cell constrains the behaviour of its constituent molecules”. That is how it “instructs” the constituent molecules what to do, which (evolutionarily) benefits the entire organism. Once the molecules have been provoked into action, due to the very encoded physical constraints of our massively complex cells and their electro-chemical processes, the molecules have no choice but to collectively act to attack the foreign virus.

The same explanation could be used to describe the process, for example, by which birds ‘intuitively’ build nests. Nest-building, rather than being a “response” to instructions from the bird-organism’s constituent genetic elements, is just what “whole” bird-organisms, under the ‘rules’ of natural selection, evolved to do. Purposively, not purposefully. The whole bird-organism ‘tells’ its constituent elements what to do, to “make it so” (ie make the nest). Consciousness and thought are completely unnecessary. The seemingly-appropriate ‘conditioned’ response is already coded in the whole creature’s very physical structure. The genes don’t tell the creature what to do; the creature ‘tells’ the genes what to do.

I found this rather mind-blowing, and would encourage you to listen to Denis explain it. This is almost the opposite of how most of us imagine how biological conditioning to work. The architecture of the entire organism, from cells to organs to systems such as the immune system, is hard-wired, physically ‘coded’ in the very structure of our cells and the other constituents of our bodies, and in their evolved processes, to condition certain behaviours to occur under certain circumstances, and to drive our genes and the other ‘working elements’ of our bodies to act accordingly. Rather than being the blueprints for our conditioned behaviours, our genes might be more accurately described as specialized foot-soldiers carrying out the organism’s encoded instructions.

How does a cell ‘instruct’ a gene to do something, strictly by virtue of its physical structure? Take a look at the staggering complexity of human cells, he says — an average of 100 trillion atoms in every cell — and appreciate that its structure, much the way an enormously sophisticated maze constrains the behaviours of humans making their way through it, “the complexity of the cell constrains the behaviour of its constituent molecules”. The cell doesn’t meekly act out the ‘genetic code’ imprinted in its genes, the cell is the ‘general’ that commands those genes to do what they have been evolutionarily specialized to do. The cells themselves, self-organized into what we collectively call organs, systems, and organisms, have evolved to be the astonishingly sophisticated intelligent ‘machines’ that manage our breathing, our blood circulation, our nervous system, and all the other ‘autonomous’ processes that keep us alive and healthy.

Denis acknowledges that to some extent the ‘orders’ can also come from below — from the genes to their cells and the whole-organism. The healthy conditioning of our ‘behaviours’ — from how we breathe and how we fight infections to how we raise our offspring — is a collaborative undertaking between all the aggregate levels and processes that comprise the organism. As Denis words it, when it comes to our conditioning “there is no privileged level of causation”. Here’s a chart from an earlier paper in which he diagrams the two-way multi-level processes by which ‘encoded’ information and instructions are communicated between levels of the organism (biological conditioning) and between the organism and other organisms (cultural conditioning):

(The Neo-Darwinists, he says, have carried out a vigorous campaign since the early 2000s to try to discredit his research and squelch some of his papers and conferences. For those interested in the degree to which much of this controversy revolves around the very term ‘causation’, the above paper also explains this, and includes a fascinating discussion of the notion of ‘entangled causation’. Here’s an example of a pretty harsh repudiation of Denis’ main assertions, if you want to see how nasty things can get between disagreeing scientists, theoreticians, and philosophers. And if you really want to get into the nuts and bolts of biophysics and purposiveness, here’s a 400-page compendium on the subject of ‘Purpose’ edited by Denis with Stewart Kauffman et al.)

So where does this leave us? The implication of this multi-level multi-directional complex conditioning that most disturbs the Neo-Darwinists is that we will look in vain for the ‘cancer gene’ and the genes that ’cause’ other diseases. Diseases are necessarily much more complex than that, and our frenzy to unlock the genetic code is not going to help us ‘cure’ diseases. Lots of research money was and is riding on that, so no wonder the Neo-Darwinists are upset.

But this interpretation doesn’t do much damage to the model of how ‘reality’ works depicted in the chart at the top of this post. The model is already ephemeral: The contents of the ‘blue’ boxes, our self and its beliefs, are mere phantoms, inventions that actually serve no purpose. The contents of the ‘green’ box, our bodies and their apparent behaviours, are just appearances, requiring an ‘observer’ to (arbitrarily) delineate and attempt to ‘make sense’ of them. And as Richard Lewontin has explained, as soon as we break things apart to try to make sense of genes, cells, organisms, and their environments ‘separately’, we destroy any possibility of understanding the processes going on ‘between’ these elements that make them what they ‘are’. It’s like dissecting a bird to understand how flight works.

So now it would seem, if Denis is correct, that the causality of conditioning, the ‘force’ that determines our behaviours, is not deducible. Everything affects (ie conditions) everything else, and how it does so can never be disentangled. It has evolved this way just because it has. Purposively, but not purposefully. To the utter horror of scientists and philosophers, it cannot be ‘decoded’ or understood. A million clever apes deploying AI supercomputing for a million years will never produce a map that can even vaguely approximate the territory.

If there even is a territory.