Midjourney AI’s take on scientists debating the existence of time and free will. Apparently Midjourney is of the impression that all scientists are male. I wonder where it got that idea? ChatGPT did no better with its all-male list of “prominent figures” on these topics. Not so intelligent.

Over the last month or two I’ve made my way through four provocative books about the nature of reality:

- theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli’s Helgoland

- quantum physicist Julian Barbour’s The End of Time

- theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder’s Existential Physics

- neuroscientist Anil Seth’s Being You

The authors of these books know, refer to, support, and sometimes criticize each other’s work. But to some extent they all represent a growing but still unorthodox school of scientists who believe, on the balance of probabilities:

- time does not exist

- the ‘self’ does not exist

- free will does not exist

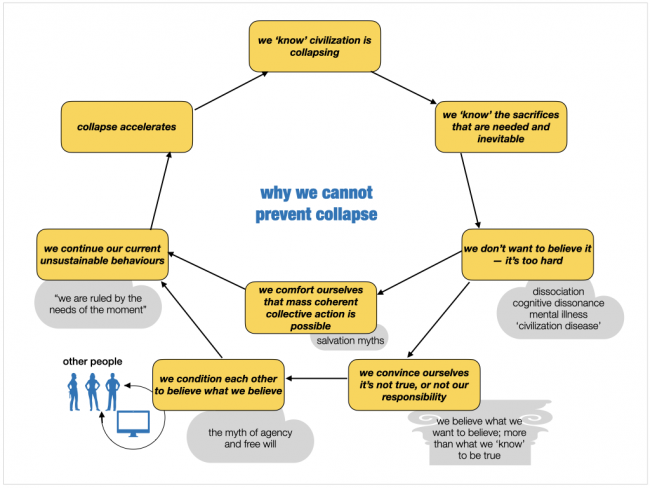

They use words like illusion, misconstrual, and even hallucination to describe what time, self and free will really are, and why they seem to exist, and how their actual non-existence does not in any way affect how the world works, or how we function in it. Unlike some more conservative, orthodox thinkers in their fields (some of whom say that widespread acceptance of our lack of free will would somehow, preposterously, inexorably lead to global chaos and anarchy), they describe how the human brain might have evolved the faulty belief in the reality of these things (we are incorrigible pattern-seekers, sense-makers, and meaning-makers, after all), and how our belief in them has not affected, and need not affect, our beliefs and behaviours — any more than our mistaken belief that the sun revolved around the earth affected them.

Three of the books tackle the issue of free will, and explain why we are not ‘responsible’ for our actions, and describe the moral dilemma that this realization presents for our systems of laws, enforcement, and incarceration. The horrific lifelong trauma, both psychological and physical, suffered by most of those who then became serious criminals is supported by mountains of data. That doesn’t ‘justify’ their behaviour, but it does explain it.

Just as journalist Michael Pollan and biologist-neuroscientist Robert Sapolski explained in their books, the argument outlined in these books isn’t that we should take no action against those convicted of crimes, but that (i) instead of using the threat of punishment and incarceration as an attempt to deter criminal behaviour and reduce recidivism, we should use counselling and other methods to treat those convicted, the same as we should for anyone else suffering from serious mental illness, and (ii) we should only incarcerate those who we perceive to pose a significant risk to others, and only until treatment of their mental illness reduces that risk.

As scientists, all four writers are most interested in how abandoning our belief in the ‘reality’ of time, self and free will, affects our overall understanding of the nature of the universe and our place in it. In that respect, accepting that time is just a mental construct is relatively easy — our new models of the universe and its workings are mostly independent of the concept of time and work just fine without it.

Likewise, setting aside the confusing plethora of words like ‘determinist’, ‘physicalist’, ‘materialist’, and ‘compatibilist’, these writers seem to accept that, regardless of its lack of intuitiveness, and the ethical dilemmas it poses, the evidence for our behaviour being completely biologically and culturally conditioned, rather than subject to free will, is increasingly compelling, and that all attempts to locate, identify, or rationalize the existence or even the need for a ‘self’, have failed.

We simply don’t need the concepts of a self, or of free will, to comprehensively explain human behaviour. In fact, our behaviour makes more sense if we acknowledge that they don’t exist. And it’s not terribly difficult to explain why our species evolved the ubiquitous misunderstanding that we have selves and free will, and the false belief that time really exists.

In short, our understanding is wrong, but it is perfectly understandable. This is how the human brain apparently makes sense of things, by creating flawed, best-that-it-can-manage models, and then adopting them as accurate representations of reality until/unless a better model can be found. This is why it is so easy for humans to get caught up in a movie, which is just pixels on a screen, and feel that its characters are real and that the events it depicts are really happening.

So why do we care? If our misunderstanding of time, self and free will doesn’t affect our behaviour, what does it matter?

It matters for the same reason that our search to understand quantum effects, and why they just don’t fit (to put it mildly) with any of our existing models of how the world works, matters to us — We want to know ‘the truth’. We endlessly seek better models that more accurately represent reality.

Some scientists are now going further. Sean Carroll, another theoretical physicist (referred to in two of these books), says that when we dispense with the concept of time, we need to also reconsider our understanding of the rest of what seems to be real. While he is holding on to a belief in the many-worlds theory, he’s also admitted that the true nature of reality can most likely never be known or understood, and that the only thing we might be able to say with any assurance about the universe is that it is “an infinite field of possibilities”.

This is not so far from the message of radical non-duality that “nothing is either real or unreal”, that everything is just “nothing appearing as everything”. If there are only appearances, then anything is possible, ie the universe is an infinite field of possibilities. (Two of the books go into why, if anything is in fact possible, most ‘improbable’ things never seem to happen, drawing largely on entropy theory. They also suggest that our categorization of the ‘arrow’ of time might be our flawed model of the apparent tendency of things towards greater entropy.)

Even if we might be persuaded that everything is just an appearance, and that nothing (including time, space, separate things, and selves with free will) is real, what does it mean when radical non-dualists say nothing is ‘unreal’ either?

By ‘unreal’ we generally mean imagined or imaginary, like a hallucination or a story. The message of radical non-duality is that time, the self, free will, and other constructions of the (apparent) brain are ‘purely’ unreal — they are just things the self conjures up and imagines to be true, because it lacks any better explanation for what seems to be happening. But “nothing appearing as everything” (all the ‘stuff’ that isn’t merely conjured up in our brain) is neither real nor unreal. In other words, it isn’t real, because nothing is separate and because there is no time for anything to ‘really’ exist in or be happening in. And it isn’t unreal, because we aren’t just imagining it. “Nothing appearing as everything” is, therefore, just an appearance. We can’t conceive of anything being neither real nor unreal (though if there’s been a ‘glimpse’ it is immediately understood), but we can kind of get the concept.

So what about ‘consciousness’?

In terms of understanding the nature of reality and the message of radical non-duality, the whole concept of consciousness, as important as it is to many scientists, theologians, philosophers, spiritualists, and psychologists, is essentially irrelevant. The term has no strict definition and is often used to mean very different things. It is, merely, another mental construct, a concept, a model, with no actual basis in reality. The entire family of similar terms — awareness, presence, self-awareness, sentience, and even knowledge — are the arrogation of qualities of the self, arrogated strictly to the self. They are scaffolding placed atop the concept of the self, and, like the self, they are just models, theories, ideas, sense-making, devices used by the illusory self to position itself (at the centre) in the model of reality that it has constructed. There is no need for something called ‘consciousness’ to ‘really’ exist, any more than there is a need for the self to ‘really’ exist. It is like the rationalization of a hallucinator for how their hallucinations are actually real.

One of the fundamental principles of science is that, in seeking to understand how something is, or works, one should look for the simplest possible explanation. We could all make up stories about fairy dust or holograms or 13-dimensional strings to try to explain how the universe unfolded or how everything fits. The problem is, every time we find an explanation that seems sensible, it turns out to be either disproven by a subsequent discovery, or crazily convoluted (like the theologians’ complicated models developed to try to refute Copernicus and Galileo) and untestable or unfalsifiable.

The message of radical non-duality, which resonates with a lot of new discoveries in both physics and neuroscience, is, arguably, the simplest possible explanation for the nature of reality. It is falsifiable — there could one day be verifiable evidence that time or the self or free will actually exists. The message is internally consistent and quite elegant in its simplicity:

- The self and all its constructs are psychosomatic misunderstandings, illusions concocted by the (apparent) brain and body to try to make sense of the signals they are receiving.

- Everything ‘else’ is only nothing appearing as everything, for no reason or purpose. Nothing that appears is real or unreal. And nothing matters.

There are obvious reasons why such a message produces rejection, outrage, dismissal and disbelief when it is heard by most people (including most scientists). Even if it is correct, it is useless. There is nothing you can do with this understanding of the nature of reality and humans’ place in it. It is immensely humbling, and thinking about it puts humans (especially scientists) on the defensive. Not only is there nothing you can do with this understanding, there is no ‘you’, no self, no thing separate that can do anything, or that ever has done anything. There is only what is apparently happening, for no reason or purpose. Everything that ‘we’ think we have done, or learned, is just a misunderstanding, a misinterpretation in the desperate attempt to make sense and make meaning of (and try to control) everything that is apparently happening, when there is no rationale or meaning for, or control over, anything.

It’s enough to make you howl in anger, indignation, and incredulousness. No, that can’t be.

Perhaps the same reaction that those who first read Copernicus’ and Galileo’s books had.

(Oh, and if you only have time to read one of the books above, I’d recommend Sabine’s, especially the excellent chapter on free will.)