| Four years ago I wrote a well-received paper entitled A Prescription for Business Innovation: Creating Technologies that Solve Basic Human Needs. I’ve updated it, broken it into three manageable pieces, and present the first part below. The remaining parts will follow on successive Tuesdays.

Introduction: Why I’m Here My modest objective in this presentation is first, to tell you some new, interesting and useful things about innovation, and, second, to persuade you that innovation is the most important determinant of every business’ success, and perhaps even the quality of our lives. I want to convince you that in your business, whether it employs one person or one million, innovation is probably the solution to whatever is currently keeping you awake at night — whether that be sales growth, cost control, customer satisfaction, employee retention, or maximizing shareholder value. And if you, like me, spend some of your sleepless hours worrying about things more altruistic than your personal and business success, I want to convince you that innovation is probably also the solution to most of the problems that have befallen our suffering planet, in part because past innovations have created many of these problems. And finally, if I’m successful in this evangelical task, I want you to leave today not only with renewed hope about the future of your company and our world, but with some new tools to make innovation happen in your business. I would like to ask you to listen to these ideas with an open mind, suspend briefly your disbelief, and give this your full attention. If this was that easy to explain, someone much smarter than I would have done it years ago. One: Learning from our past: How Need Drives Innovation

The catch-phrases of these business-driven thought leadership events are not new: competitive advantage, sustainable development, the connected knowledge economy, globalization, convergence, digitization, moving at the speed of thought. What is new is that there are now three divergent models being used to predict our future, fighting for audience attention (the names assigned to them are mine):

From the perspective of business innovation this matters because almost everyone agrees that the successful businesses of the future will be complex, adaptive, agile, proactive, and creative — they will not wait for market demands to change them, but will instead continuously reinvent their companies, anticipate future demands, and make strategic, risky, value-creating investments and decisions, what John Kotter calls Leading Change. In order to do this — to make intelligent decisions and investments before demand is articulated, to view risk-taking and the creation of future options for action as essential, not foolhardy — requires at least some consensus about ‘where the future is headed’. Selecting one of the above three theories about the future is an important start in doing so. Technophiles who favour the Acceleration Model tend to be infatuated with artifacts of the last thirty years: more digital, faster, smaller, lighter. Advocates of the Chaos Model, on the other hand, believe there are no rules for our brave new world of the 21st century. Their advice for business and other leaders is to be opportunistic and think short-term. I lean towards the Evolutionary Model. I believe that using an understanding of the past, with the right perspective, can help businesses anticipate the future with exceptional clarity and probability of success. There are two reasons I hold this belief, and they form the basis for much of the rest of this presentation:

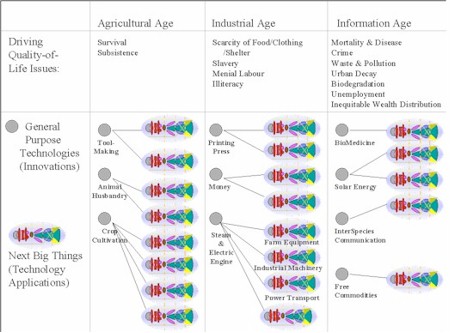

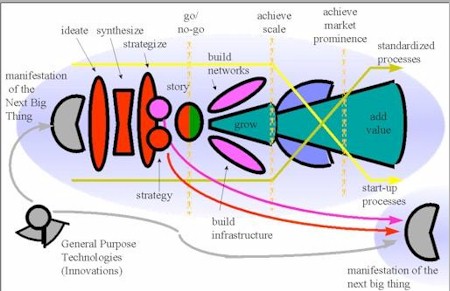

The report of the 1999 Credit Suisse First Boston New Economy Forum draws together some very powerful innovation models, into a single synthesized model that can be used to explain how technologies have impacted society and civilization since it began about thirty millennia ago: According to this model, innovations like crop cultivation, the printing press, and the harnessing of solar energy, have always arisen in response to an urgent human need — overcoming the sudden food scarcity after the Ice Age, bringing literacy to the masses, and solving the energy crisis respectively in these three examples. Technologies are applications of these innovations. The intriguing organic-looking ovals for each technology are also from the Credit Suisse Synthesis, which proposes are technologies are best developed using the following process: Let’s now take a look at this synthesis model in more detail, to test whether it represents the way in which historical innovations have occurred, and then what this might tell us about innovations of the future. Two: Man’s Earliest Innovations: A Brief History of Technology So picture our poor shivering proto-human looking among the bones of a wolf’s recent meal for new tools beside the greasy bone, and thinking, in true McLuhanesque and 20th century economics terms: ‘If the bone as an extension of my hand helps me to compensate for my competitive disadvantage in the hunter-gatherer marketplace, why can I not use other tools similarly? Then, lacking the appropriate scientific training but still intoxicated over his first innovation, he or she comes across a dead wolf and considers the following applications of this technological insight:

Of course, the correct answer is (c), which, except for the use of a leash or harness instead of a tight strap, remains one of the most important technologies in our short human history: animal domestication. Interestingly, the development of a non-choking animal harness, and a stirrup for riding larger animals, took centuries, according to a review in the Economist of the last millennium’s greatest inventions. What’s more, it occurred first in China, possibly enabling their civilization to develop much more quickly than Western civilization, until, for reasons only hinted at in the Economist , China suddenly stopped developing new technologies in the 15th century. Without animal domestication and crop cultivation, we as a species might well not have survived to come up with newer and more sophisticated innovations like the wheel, paper and the computer. Three: Six Principles about the Innovation Process The first humans used precisely the process shown in Figure Two to develop and ‘commercialize’ the technology applications of the innovations of animal domestication and crop cultivation. It is the same commercialization process taught in business schools today. However, the success of the process is only as good as the idea, the innovation, that lies at its front end. Business schools are actually very good at explaining the recipe, but they, and most educational and business institutions, are absolutely terrible at teaching people how to find the essential new ingredients — the ‘grey matter’ at the left side of Figure Two, the ideas & innovations that make the recipe work. The problem isn’t a scarcity of good ideas either — it is the lack of rigour and investment in infrastructure to surface, capture, develop and qualify new ideas prior to commercialization. Figure Two also recognizes that many innovations and technologies are derived from other innovations and technologies, and often come from applying an idea or a technology from one application domain, or from nature, to an unrelated application domain. The BBC/Discovery program Connections made this point very powerfully, and its author James Burke continues to develop both examples of such non-obvious connections, and exercises to help us learn to discover more — in essence, to become more innovative. Burke’s latest book explains how a problem with the irrigation of Italian gardens led to the invention of the carburetor, for example. Furthermore, Figure Two acknowledges the importance of the story in the successful commercialization of innovations. It is hard to pick up a business book or attend a business conference these days without being lectured on the importance of story-telling, but the idea is neither new nor complicated: Stories convey the context for the application, they explain how it can be used in the user’s or developer’s day to day life. Knowledge transfer is an essential precondition to commercialization. The easiest way to transfer knowledge, i.e. to explain or persuade, is to do so in a way that lets the learner internalize what they are hearing i.e. to fit it into their own mental models of how things work. And the simplest way to enable internalization is by telling a story, be it a Utopia or Future State Vision, a parable with a built in lesson, or a simple recounting of processes and events that lets the learner relive the teacher’s experience as if it were their own. From all this we can derive six basic principles about the Innovation Process (again, the names given to them are mine), to add to the two espoused earlier about cultural resistance to innovation:

(Next Tuesday: Part Two: Innovation & Society, and The Structure & Culture of Innovative Organizations (with six additional Innovation Principles to add to the eight above); The Following Tuesday: Part Three: A 15-step Prescription for an Innovative Organization, with some examples.) |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

Great listing of principles. I think if we could get the principles of innovation right, we could make much more progress than our current search for the “golden” tool, technique, process that will give us innovation without having to work for it. I’m delighted to link this article to our innovation blog: http://thinksmart.typepad.com/headsup_on_organizational/Keep up the great work!