My last important learning before I left Ernst & Young was the astonishing discovery that almost none of what business presenters say gets ‘correctly’ understood, internalized, or learned by their audience. By ‘correctly’ I mean what the audience thought the message was, is almost always radically different from what the presenter intended the message to be. I base this conclusion on entirely anecdotal evidence: Throughout 2003, as a result of consternation about how so little of my presentations was sinking in, out of curiousity I began systematically debriefing with a few audience participants in each presentation I attended (whether or not I had been one of the presenters), as soon as possible after the presentations, and then fed back to the presenters what the audience said. The result was usually anger or stunned disbelief. Here are my totally unscientific findings from this ‘research’:

The good people at E&Y are very intelligent, motivated individuals, and some of them are quite good at making presentations clear, articulate and interesting. So I confess I was amazed to discover the almost complete lack of communication that occurs in most presentations. Given what I’ve read by Nancy Dixon and George Lakoff on the importance of adapting your message to each listener’s ‘frames’ if you want to be understood, I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised. Lately most of my meetings have been one-on-one, so I’ve started to look at conversations with the same skeptical eye as presentations. How much do we get out of them really, and are they truly about communicating or actually about something else? So far I’m just listening to others’ conversations, whenever I get the opportunity. Since I’m male, you will appreciate that this is very difficult for me to do! But I’m also finding out (as most women already know well) that it can be very entertaining, if you pay attention to the whole conversation and not just to the words being said. I’m starting to think conversations are as useless a medium for effective intellectual communication as presentations. It’s too early for me to present any unscientific conclusions, but here’s what I’ve observed so far — I’d love to hear what you think about all this:

What have you observed from watching and listening to conversations? Is it just me, or do most of us seem to be remarkably inept and awkward at doing something that is crucially important, something we spend so much time doing? What’s the one thing (besides improving our listening skills, of course) we could do to improve the quality and value of our conversations? |

Navigation

Collapsniks

Albert Bates (US)

Andrew Nikiforuk (CA)

Brutus (US)

Carolyn Baker (US)*

Catherine Ingram (US)

Chris Hedges (US)

Dahr Jamail (US)

Dean Spillane-Walker (US)*

Derrick Jensen (US)

Dougald & Paul (IE/SE)*

Erik Michaels (US)

Gail Tverberg (US)

Guy McPherson (US)

Honest Sorcerer

Janaia & Robin (US)*

Jem Bendell (UK)

Mari Werner

Michael Dowd (US)*

Nate Hagens (US)

Paul Heft (US)*

Post Carbon Inst. (US)

Resilience (US)

Richard Heinberg (US)

Robert Jensen (US)

Roy Scranton (US)

Sam Mitchell (US)

Tim Morgan (UK)

Tim Watkins (UK)

Umair Haque (UK)

William Rees (CA)

XrayMike (AU)

Radical Non-Duality

Tony Parsons

Jim Newman

Tim Cliss

Andreas Müller

Kenneth Madden

Emerson Lim

Nancy Neithercut

Rosemarijn Roes

Frank McCaughey

Clare Cherikoff

Ere Parek, Izzy Cloke, Zabi AmaniEssential Reading

Archive by Category

My Bio, Contact Info, Signature Posts

About the Author (2023)

My Circles

E-mail me

--- My Best 200 Posts, 2003-22 by category, from newest to oldest ---

Collapse Watch:

Hope — On the Balance of Probabilities

The Caste War for the Dregs

Recuperation, Accommodation, Resilience

How Do We Teach the Critical Skills

Collapse Not Apocalypse

Effective Activism

'Making Sense of the World' Reading List

Notes From the Rising Dark

What is Exponential Decay

Collapse: Slowly Then Suddenly

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Making Sense of Who We Are

What Would Net-Zero Emissions Look Like?

Post Collapse with Michael Dowd (video)

Why Economic Collapse Will Precede Climate Collapse

Being Adaptable: A Reminder List

A Culture of Fear

What Will It Take?

A Future Without Us

Dean Walker Interview (video)

The Mushroom at the End of the World

What Would It Take To Live Sustainably?

The New Political Map (Poster)

Beyond Belief

Complexity and Collapse

Requiem for a Species

Civilization Disease

What a Desolated Earth Looks Like

If We Had a Better Story...

Giving Up on Environmentalism

The Hard Part is Finding People Who Care

Going Vegan

The Dark & Gathering Sameness of the World

The End of Philosophy

A Short History of Progress

The Boiling Frog

Our Culture / Ourselves:

A CoVid-19 Recap

What It Means to be Human

A Culture Built on Wrong Models

Understanding Conservatives

Our Unique Capacity for Hatred

Not Meant to Govern Each Other

The Humanist Trap

Credulous

Amazing What People Get Used To

My Reluctant Misanthropy

The Dawn of Everything

Species Shame

Why Misinformation Doesn't Work

The Lab-Leak Hypothesis

The Right to Die

CoVid-19: Go for Zero

Pollard's Laws

On Caste

The Process of Self-Organization

The Tragic Spread of Misinformation

A Better Way to Work

The Needs of the Moment

Ask Yourself This

What to Believe Now?

Rogue Primate

Conversation & Silence

The Language of Our Eyes

True Story

May I Ask a Question?

Cultural Acedia: When We Can No Longer Care

Useless Advice

Several Short Sentences About Learning

Why I Don't Want to Hear Your Story

A Harvest of Myths

The Qualities of a Great Story

The Trouble With Stories

A Model of Identity & Community

Not Ready to Do What's Needed

A Culture of Dependence

So What's Next

Ten Things to Do When You're Feeling Hopeless

No Use to the World Broken

Living in Another World

Does Language Restrict What We Can Think?

The Value of Conversation Manifesto Nobody Knows Anything

If I Only Had 37 Days

The Only Life We Know

A Long Way Down

No Noble Savages

Figments of Reality

Too Far Ahead

Learning From Nature

The Rogue Animal

How the World Really Works:

Making Sense of Scents

An Age of Wonder

The Truth About Ukraine

Navigating Complexity

The Supply Chain Problem

The Promise of Dialogue

Too Dumb to Take Care of Ourselves

Extinction Capitalism

Homeless

Republicans Slide Into Fascism

All the Things I Was Wrong About

Several Short Sentences About Sharks

How Change Happens

What's the Best Possible Outcome?

The Perpetual Growth Machine

We Make Zero

How Long We've Been Around (graphic)

If You Wanted to Sabotage the Elections

Collective Intelligence & Complexity

Ten Things I Wish I'd Learned Earlier

The Problem With Systems

Against Hope (Video)

The Admission of Necessary Ignorance

Several Short Sentences About Jellyfish

Loren Eiseley, in Verse

A Synopsis of 'Finding the Sweet Spot'

Learning from Indigenous Cultures

The Gift Economy

The Job of the Media

The Wal-Mart Dilemma

The Illusion of the Separate Self, and Free Will:

No Free Will, No Freedom

The Other Side of 'No Me'

This Body Takes Me For a Walk

The Only One Who Really Knew Me

No Free Will — Fightin' Words

The Paradox of the Self

A Radical Non-Duality FAQ

What We Think We Know

Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark Bark

Healing From Ourselves

The Entanglement Hypothesis

Nothing Needs to Happen

Nothing to Say About This

What I Wanted to Believe

A Continuous Reassemblage of Meaning

No Choice But to Misbehave

What's Apparently Happening

A Different Kind of Animal

Happy Now?

This Creature

Did Early Humans Have Selves?

Nothing On Offer Here

Even Simpler and More Hopeless Than That

Glimpses

How Our Bodies Sense the World

Fragments

What Happens in Vagus

We Have No Choice

Never Comfortable in the Skin of Self

Letting Go of the Story of Me

All There Is, Is This

A Theory of No Mind

Creative Works:

Mindful Wanderings (Reflections) (Archive)

A Prayer to No One

Frogs' Hollow (Short Story)

We Do What We Do (Poem)

Negative Assertions (Poem)

Reminder (Short Story)

A Canadian Sorry (Satire)

Under No Illusions (Short Story)

The Ever-Stranger (Poem)

The Fortune Teller (Short Story)

Non-Duality Dude (Play)

Your Self: An Owner's Manual (Satire)

All the Things I Thought I Knew (Short Story)

On the Shoulders of Giants (Short Story)

Improv (Poem)

Calling the Cage Freedom (Short Story)

Rune (Poem)

Only This (Poem)

The Other Extinction (Short Story)

Invisible (Poem)

Disruption (Short Story)

A Thought-Less Experiment (Poem)

Speaking Grosbeak (Short Story)

The Only Way There (Short Story)

The Wild Man (Short Story)

Flywheel (Short Story)

The Opposite of Presence (Satire)

How to Make Love Last (Poem)

The Horses' Bodies (Poem)

Enough (Lament)

Distracted (Short Story)

Worse, Still (Poem)

Conjurer (Satire)

A Conversation (Short Story)

Farewell to Albion (Poem)

My Other Sites

While I have noticed the same thing about presentations and have taken many of the steps you advocate (to mixed success), I hadn’t really thought much about conversations in the same light. I do have a tendency to “watch” others in conversation and learn as much from the process of the conversation as I do the content. As an “outsider”, conversations are a good way to discover many things.What I had not really thought about, though, was my own participation in conversations. Looking back on a few recent ones, I realize that my productive conversations may not be very entertaining because I do go straight to the point. I’m not very good at small talk in any setting, but I have a tendency to ignore it all together when I’m discussing something “work related” with my co-workers. (I do make sure I take time to have “meaningless” [from a work perspective]conversations with my co-workers so they don’t get too upset with me.)– Brett

I’ve noticed:People rarely say what they’re thinking.Some people say everything they’re thinking (never an unuttered thought), so it’s nearly impossible to determine what’s worth attending to. People don’t speak the way others like to listen, so listeners don’t hear what they’d like to hear.People don’t listen with an open mind, so dialogue is rare.People digress. They don’t finish their thought. They get distracted and go off on tangents.People interrupt each other.Etc.”Communication is hard.”

Brett: I also find dealing with the ‘small talk’ the most challenging part of conversations. I’ve been told it’s essential to establishing trust for many people. Kind of like foreplay, I guess ;-)Denny: I wonder why this is? My sense is that if the subject is really important, conversational behaviours are much better. Maybe the problem is we don’t know, or don’t care, or have forgotten what’s really important, so our heart isn’t in the things we talk about *instead*.

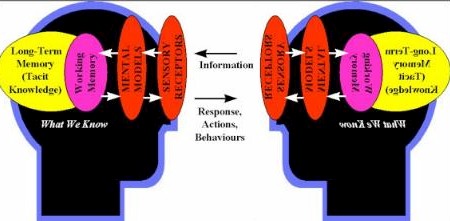

One useful technique I’ve learned over the years is the use of questions in a conversation, with careful attention to the assumptions implied by a question. For example, when a disagreement surfaces, it’s often appropriate to enter a round of questioning each other to explore whether you’re actually disagreeing on a commonly understood assertion, or just talking past each other.Also, a point on the picture at the top of the article: the “sensory receptors” aren’t passive “faithful recorders”, but active filters; among other things, this can affect the way a conversation goes. It’s quite literally true that A may hear, at a low level of processing, something different than B said.

These observations are interesting, particularly as they’re not trying to push any theory of communication.I had a few shocks when I took part in a retreat in which silence was the rule for most of the time, but for some exercises in which people in pairs took it in turns to talk for five minutes. The listener just had to listen – no nodding, encouraging or any of the usual prompts. It was fascinating from both sides, but I learned more as a listener – how hard it is to shut up, and how false a lot of these ‘encouraging’ responses can be – but often how necessary. I guess that’s why so many people go into therapy – they are essentially paying someone to shut up for an hour and not bring in ‘Oh I did that’ or ‘That’s like me, I …’.

If have a simple conversation its very hard, try to have an intercultural conversation, for instance in the Latin cultural the physical aproach and the physical contact are very important and i dont know why we use to speak very Loud (specially the Italians and Cubans) this are caracteristics that seems anoying to the saxon culture and sometimes its quite intimidating for both parts so what i recomend in this situations its to study a little bit more the “non language comunication” of the counterpart in if its posible previously talk with someone else (with the same background) before our definitive appointmentMiguel E. Pancardo T.

living in korea has taught me much about communication, particularly the ability to express myself as well as understanding others without perfect knowledge of cultural communication tools. we have differing values concerning types of conversation, interruption intervals, and esp eye-contact timing. i’ve become out-of-tune with the ‘western approach’ to communication. it has become much more difficult to speak in full sentences and carry out complete thoughts, particularly with people i don’t know. at times, i’m hyper-aware of the self who’s speaking, which disorients my train(s) of thought. communication here as a foreigner can be an interesting experience. if with koreans, we are generally super-quiet with intermittent spotlights shining upon us. but it’s pretty amazing to come to an understanding of language that releases you from the mundanity of individual words and sentences to clearly listen to a language as music and to ‘see’ personalities displayed. you come to know people for those beneath the language. i think there are two things conversations are geared towards: transfering knowledge/information; and trying to express who we think we are at the moment. the first is preordained or designed with Q&A in mind, and the second for listening. use for knowledge is concerned with how the external world relates to our internal one. i think we are inept at conversation because we don’t spend enough time thinking, and because we don’t have enough confidence in ourselves. we do not internalise the knowledge we acquire. and we don’t seem to have the appropriate language skills to have a healthy debate. my own writing skills are falling short of what i’m trying to express. i hope this has been of some interest. (lack of faith here ;)

Most people are putting most of their attention on what they plan to say during the next lull in conversation while their conversation buddy is talking. So in reality, so many conversations are truly with yourself. I know I’m guilty of this.

As always, a wonderful post with great commentors. My first thought: my mother-in-law. She prides herself in not speaking what she wants yet she expects people to understand her 100%. What??? I know, it’s strange. But the point is, a lot of people speak in code. Once you know the code, then its easy. I think this happens with the two big sides in politics: progressives versus conservatives. But in little ways, this is what happens.

It is unrealistic to expect someone to understand what you are saying when they believe their job depends upon them continuing to not understand. Substitute freely for the word “job” and it still holds true.

Don: Absolutely. When I flipped the graphic to make a mirror image I was originally planning on cleaning up the backward text — then I realized that this unintelligable writing emphasized just how different each of our mental models and perceptual filters really are.Norman: I’m the same way — my wife says the only time I shut up is when I talk on the phone with my father, who I rarely see (he’s 80), and who, along with some wonderful lessons and traits, also taught me the bad habit of starting to think about my reply before I finished listening to what the person I’m talking with (to?) is saying.dN: Well put. Maybe one of the reasons a lot of us blog is that it’s easier than conversing, and gives us what conversation doesn’t — sufficient time for thought and reflection.Birdie: Mea culpa also.